SÃO PAULO, Brazil – As the COVID-19 pandemic surges across Brazil, the Bishops’ Conference’s Prison Pastoral Commission is urging the country’s authorities to take critical measures to avoid a massive contamination in the already chaotic Brazilian prison system, including the release of detainees.

Since the confirmation of the first case of the disease in the South American country, on February 26, there were 8,066 new documented occurrences and 327 deaths. So far, there has been no official declaration from the authorities concerning cases in the Brazilian prison system; but throughout the country, there have been several reports on the possible contamination of prisoners and employees.

The website Universo Online reported on March 28 that two inmates died at a penitentiary in the city of Guarulhos, in the São Paulo metropolitan area, with difficulty breathing. Their deaths, however, were officially documented as by “natural causes.”

Suspected cases were also identified at a correctional facility in the State of Rio de Janeiro. After being examined, four detainees were considered as potentially having the coronavirus, but no conclusive tests were conducted. Governor Wilson Witzel ordered the isolation of the prisoners, but there are no separate cells or rooms for them in the facility, reported The Intercept Brasil.

The Prison Pastoral Commission has been alerting the authorities over the past few weeks about the catastrophic consequences of the new coronavirus in Brazilian prisons.

“The prison population is undoubtedly one of the most vulnerable groups in our society and would suffer the worst repercussions of the pandemic. There’s a structural problem in the penal system, which is its overcrowding,” said Father Almir Ramos, coordinator of the Prison Pastoral Commission in the city of Florianópolis, where he also works as a nurse at a public hospital.

Ramos said the unhealthy and overcrowded Brazilian prisons are very conducive for the spread of the virus.

“Diseases that are transmitted through physical contact are usually a problem in prisons. In the case of COVID-19, we’re dealing with infection through the air, which is much worse,” he explained.

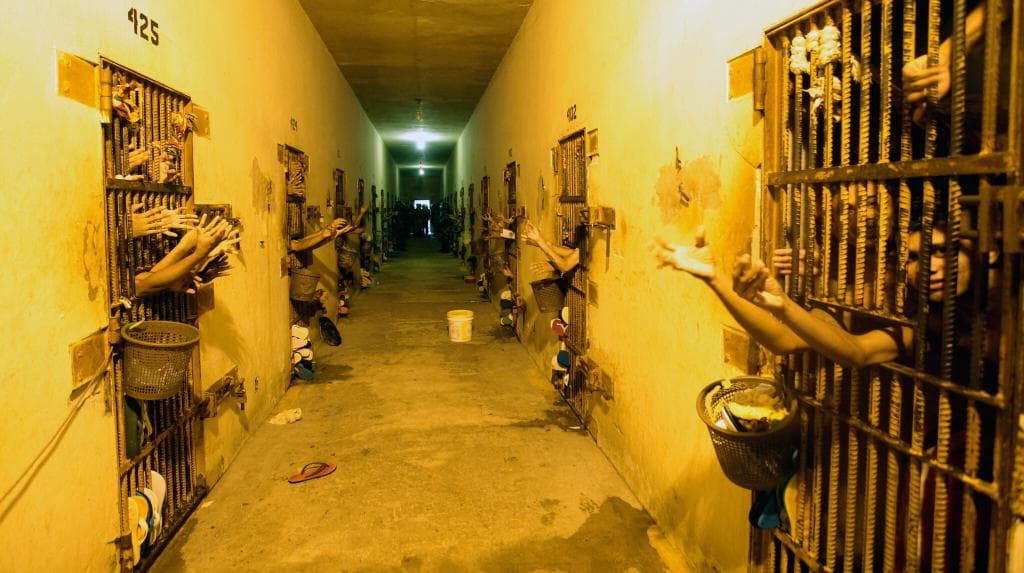

Sanitary conditions in Brazilian correctional facilities are notoriously poor. Over the years, the Prison Pastoral Commission has complained numerous times about the general lack of hygiene in prisons all over the country. Sewage leaks, accumulation of garbage, insufficient or nonexistent distribution of cleaning products, infestation of rats and other vermin, and the absence of tap water in cells are common problems.

The situation is made worse with the system’s overcrowding. The maximum capacity of prisons in the country is 437,912 people; but there are at least 729,949 people currently incarcerated.

“Such population is mainly constituted of young men with deficient immunity, many of them suffering with furunculosis, scabies, and tuberculosis. The system is deteriorated, so the necessary measures of sanitation are hard to implement,” federal judge João Buch told Crux.

“I’ve already discovered terrible situations, such as an overcrowded cell in which 30 inmates were side by side with three men with confirmed cases of tuberculosis,” he said.

The Ministry of Health said 10 percent of the total number of cases of tuberculosis in Brazil in 2018 were among prisoners and other detainees, according to Agência Pública. The incidence of tuberculosis in prisons is 35 times higher than in the general population. The Ministry of Justice says that 62 percent of the total deaths that occur in Brazilian prisons are caused by diseases such AIDS, syphilis and tuberculosis.

In an open letter released on March 13 and signed by Sister Petra Pfaller, national coordinator of the Prison Pastoral Commission, the organization said that the “consequences will be disastrous” if COVID-19 spreads through the Brazilian penal system.

According to Pfaller, the first preventative measure would be to immediately stop incarcerating more people to avoid the continual growth of the overcrowding rate and the resulting deterioration of sanitary conditions.

“Other countries, such as Germany, have taken such measure,” the religious sister told Crux.

Other actions advocated by the Prison Pastoral Commission include the possible liberation of distinct groups of inmates, many of them already legally able to be released.

“There’s a gigantic prison population formed by people who have not been sentenced yet and have the right to wait in freedom for their sentences to be announced,” Pfaller explained.

Pregnant female prisoners and inmates on work release (who work during the day and go back to prison at night) should also be freed, she said.

“It doesn’t mean that the State is opening the prison’s doors and liberating everybody, but there’s a large prison population that could be immediately released,” argued Pfaller.

On March 17, the National Council of Justice (known as CNJ, in Portuguese) published a recommendation to judges and courts related to the adoption of prevention measures to avoid the spread of the disease in the penal system. Many of the suggestions of the Prison Pastoral Commission have been ratified, such as the reevaluation of provisional arrests for members of the groups at high risk of infection by coronavirus and the anticipated release of some prisoners.

“The CNJ’s recommendation helped to encourage more judges to release groups of prisoners, especially the ones in semi-open conditions. But we don’t have much reliable information at this point, everything is very messy,” said Pfaller.

Riots have been reported in several correctional facilities in Brazil due to the coronavirus pandemic. Some Brazilian states have banned temporary leaves from prison for prisoners who have the right to go back to their homes in a few occasions during the year, and those kinds of measures motivated the disturbances. That was the case in the State of São Paulo, where there was a wave of prison riots and a mass prison escape on March 16. At least 1,300 inmates have fled different correctional facilities in the state, with only some later recaptured.

On March 28, another prison riot took place in Rio Grande do Sul State. Inmates allegedly required the release of part of the prisoners in order to avoid the dissemination of the virus.

The Prison Pastoral Commission fears that extraordinary provisions to restrict visits and temporary leaves will result in the violation of the inmates’ rights.

“We know there’s the practice of torture in Brazilian prisons. Without visits, they may increase. The situation is already catastrophic. Now they have the argument of the virus,” said Pfaller.