ROSARIO, Argentina – Bishop Pere Casaldáliga, born in Spain in 1928, died on Saturday in Brazil, at the age of 92. He was a missionary bishop, a member of the Claretian order, who spent most of his life in the Amazonian region of Mato Grosso. After arriving in Brazil in 1968, he never again returned to Spain, not even for his mother’s funeral.

He was buried with a stole created for him by the indigenous peoples he served, and a picture of his casket showed him barefoot.

He was a man who chose not to have a TV and a fridge in his home, saying he was waiting for when “everyone has one” before getting them for himself.

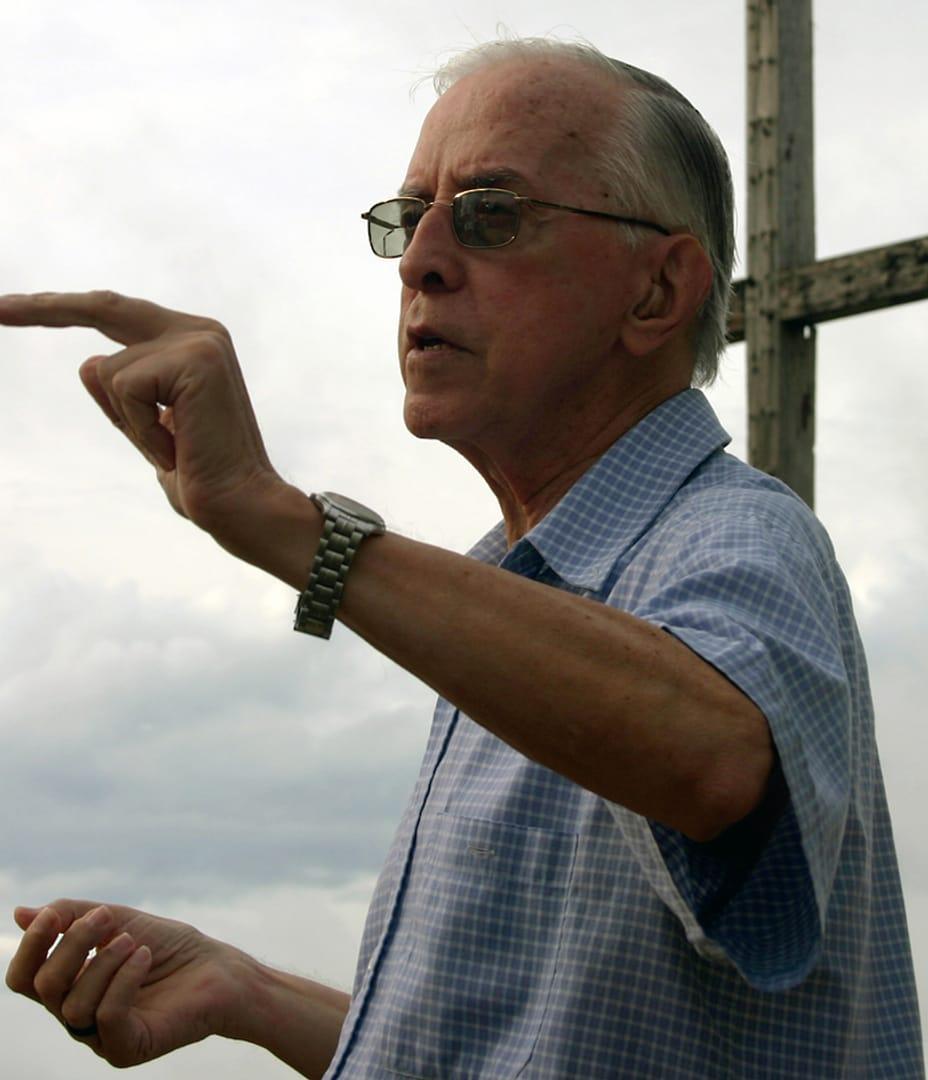

Casaldáliga was the Bishop Emeritus of the Prelature of São Félix do Araguaia and famous for his defense of the rights of the indigenous people of Brazil.

Soon after being ordained a bishop, he published a pastoral letter titled “The Church of the Amazon in conflict with large landowners and social marginalization,” in which he denounced the situation of slavery and violence suffered by the peoples and communities in the region. He also denounced the environmental problems the indigenous people faced and claimed large landowners were committing genocide against the indigenous peoples with the complicity of the then-military government.

This letter, and the work he carried out during his life, gained him great renown as a spokesperson of the Brazil’s indigenous people and the peasants of the country; it also garnered him many death threats.

He was also one of the founders of the Indigenous Missionary Council and of the Pastoral Land Commission, organizations still active today.

The Brazilian military government tried to expel him at least five times, but according to the obituary released by the Claretians, Pope Paul VI intervened to keep him in Brazil: “He who touches Peter, touches Paul,” the pontiff reportedly said.

Though he died at peace with the Holy See – he was consulted by Pope Francis during the writing process of Laudato Si’, the pontiff’s 2015 environmental treatise – Casaldáliga was many times at odds with the Vatican, particularly during the papacies of St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, who were often critical of liberation theology.

The Spanish missionary too was critical of the Vatican, particularly the Roman Curia – the Church’s central government – but also of other things surrounding the papacy, from the clothes used by the pontiff to the use of grandiloquent titles such as “Holy Father.”

He was also critical of papal travel, saying it sometimes impeded inter-Christian dialogue and steadily refused to go to Rome for the mandatory, quinquennial ad-limina visits bishops conferences make to the Vatican until 1988.

In a 1986 letter to John Paul sent ahead of the ad limina visit, the bishop expressed his hopes for an honest dialogue with the pope, and gave him a heads up for some of the issues he wanted to discuss, from the “strong marginalization of women in the Church,” to mandatory celibacy for priests in the Latin Rite.

But beyond internal ecclesiastical matters, Casaldáliga also warned John Paul that the “danger of communism will not justify our omission or our collusion with capitalism.”

“That omission or collusion may one day dramatically ‘justify’ the revolt, the religious indifference or even the atheism of many, especially among the militants and in the new generations,” the bishop wrote. “The credibility of the Church – and of the Gospel and of the very God and Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ – depends, to a great extent, on our ministry, critical, yes, but committed to the cause of the poor and to the processes of liberation of the peoples secularly dominated by successive empires and oligarchies.”

He compared the many invasions of John Paul’s native Poland to those perpetrated by the United States in several Central American countries and challenged the pontiff for his willingness to dialogue with the Regan administration but not with the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua.

“The United States itself exports its sects to these [Central American] countries, which internally divide the people and threaten the Catholic faith and the faith of other evangelical Churches,” Casaldáliga wrote.

The long letter, available online, is a summary of the thoughts of this man who described himself as a priest, a writer and a poet, an exponent of Liberation Theology, and who while pronouncing himself faithful to the pope as successor of Peter, also challenged John Paul II not to ignore “your mission as Universal Pastor” by pretending that “you don’t know about and even care about this whole ecclesial movement,” that was simmering in Latin America after the Second Vatican Council.

Follow Inés San Martín on Twitter: @inesanma