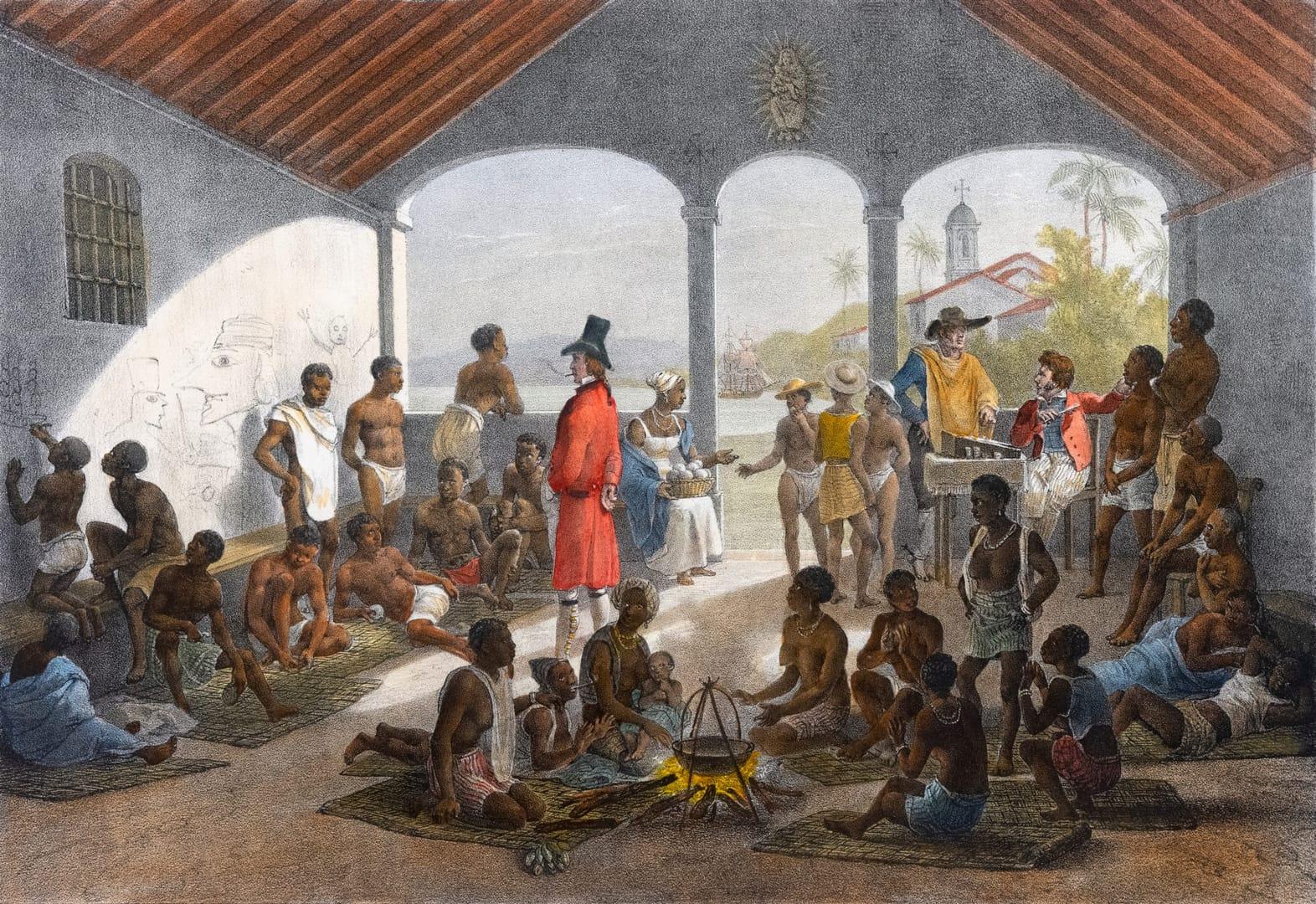

SÃO PAULO – In a year the Black Lives Matter movement spread across the globe, Brazilians are beginning to focus on the role the Catholic Church played in the institution of slavery in the country.

Slavery was legal in the South American country from its founding as a Portuguese colony in the 1500s and continued after Brazil gained its independence as the Empire of Brazil in 1822. Slavery wasn’t abolished until 1888, over 20 years after the United States.

It is estimated nearly 5 million people were transported to Brazil from Africa, more than any other country in the Western hemisphere.

A new wave of new historical research about the role of the Church during the slavery has shown how Catholic institutions in Brazil not only endorsed and gave ideological support to the system, but also directly took part in it.

“Since the 1980s, many Black activists have taken the lead and started to write their own history. This is in part a reaction to the ethnocentrism and religious intolerance that have been haunting Brazilian society,” said Deacon Sérgio Vasconcelos, a theology professor at the Catholic University of Pernambuco.

One of these scholars is Victor Monteiro Franco, a PhD student who’s doing research about the “slaves of religion,” the term used for Black people owned by religious congregations during colonial and the post-colonial imperial era in Brazil.

Franco discovered that while most properties in the cities around Rio de Janeiro had an average of 16 slaves in the 19th century, the Benedictine order owned 1,200 slaves.

“They had a large farm that not only produced beans, rice, and yuca flour, but also had cattle and manufactured pottery. They owned slave boatmen who sailed across the Guanabara Bay,” he told Crux.

In the country as a whole, the Benedictines owned a total of 4,000 slaves, Franco added.

Given the closeness of the Church with the Portuguese colonial authorities – and, after the independence in 1822, the Brazilian emperor – religious records often functioned as civil documents. “A slave’s baptism certificate was also used as the ownership title by his master,” Franco said.

It was up to the slaveholders to baptize their recently acquired slaves and to instruct them on the Catholic faith.

“Visiting priests inspected the farms and gave recommendations to each one of them, like ‘certify yourselves that the slaves are following the Church’s precepts accordingly’,” he added.

A few documents give a hint on how the monks treated their slaves.

“It varied, mostly,” Franco explained.

In one document, he discovered that a monk who had been training slaves to be blacksmiths had to be removed because he was too harsh with them.

“Last week, I saw the records of a case of a slave who died after being whipped in a Benedictine farm in Cabo Frio. The monk in charge was arrested and brought to Rio de Janeiro,” he said.

But other documents show that some monks had a good relationship with the slaves and were loved by them, Franco said.

“In general, the monks acted like the rest of the slaveholder elite in Brazil. The difference was that they saw the slaves not only as their property, but also as their spiritual flock. To Christianize them was very important,” he said.

From an ethical point of view, the monks’ individual actions were greatly limited, Franco explained.

“Even if a monk wished to liberate a slave, he had to follow his superior’s rules concerning the right age to do it and the specific monetary value that should correspond to it,” he said.

In fact, Vasconcelos said religious congregations played an important role in the country’s slave system.

“The ‘pieces from Guinea’, as the slaves were called, were brought to work in the religious schools in order to make the missions possible,” he said.

In many colonial-era monasteries, it’s possible to see a senzala (a slave house, in Portuguese), Vasconcelos added.

“Religious orders bought and sold slaves. All colonial monuments were built with slave labor,” he told Crux.

While the clergy – especially the Jesuits, as dramatized in the 1986 film The Mission – struggled against the enslavement of indigenous peoples, the enslavement of Africans was never really questioned by the Church, said Vasconcelos.

“Usually, the Church only reacted to abuse and violence, getting to the point of refusing to give communion to slaveholders who treated their slaves poorly. But it failed to express any kind of criticism against slavery itself,” he explained.

“And the Church remained mostly out of the abolitionist movement at the end of the 19th century,” Vasconcelos added.

Some of the slave’s survival strategies in that regime were also connected to the Church, like the so-called brotherhoods of Black men, Catholic lay fraternities that gathered slaves and free Black people.

“Such associations owned their churches and cemeteries and paid a stipend to a chaplain. It was an ecclesial organization that was not connected to a parish, which was very threatening for the Church as an institution,” historian Mariza de Carvalho Soares, a retired professor of the Fluminense Federal University, told Crux.

The Black brotherhoods enjoyed some financial and administrative autonomy and allowed their members to find solutions for their daily problems, even helping them in some cases to achieve freedom.

“They were spaces of relative freedom and resistance, given that they gave their members the possibility of endure some of the hardships of slavery,” said Soares, who wrote People of Faith: Slavery and African Catholics in Eighteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro.

But at the end of the 18th century, the Church began to take a firmer hold on the Black brotherhoods, even closing some of them.

“The Church always considered that the Black brotherhoods were a way of attracting Africans. But even the reduced autonomy they had was considered to be too much, and the Church acted to curtail it,” she added.

The study of the Church’s role in slavery in Brazil shouldn’t be seen as an attack to Catholicism, said Franco.

He emphasized that the whole society was involved in the system. Besides the Benedictines, the Carmelites and the Jesuits – until they were expelled from Portugal and its colonies in 1759 – were big slaveholders.

“But maybe such findings could lead the Church to reflect on itself and prompt the adoption of a critical perspective on its role,” Franco said.

According to Vasconcelos, the Church took a very important step to acknowledge the struggle of Afro Brazilians in 1988 – the 100th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Brazil – choosing the Church and Black people as the theme of that year’s Lenten social campaign.

“The Church only then faced its origins for the first time. And even then, part of its conservative segments didn’t accept it and boycotted the campaign,” Vasconcelos said.

Nevertheless, the movement generated relevant changes and the organization of Black Catholic initiatives, including the Afro Pastoral Commission.

Many in the Church, however, do not want to talk about the past.

“For some monks, slaves are something that belong to the past,” Benedictine Father Mauro Fragoso told Crux.

Fragoso is in charge of the archives of the Benedictine monastery in Rio de Janeiro.

“In general, the Church has neglected its slavery-era history. Many religious congregations’ archives across the country are not being adequately kept. Many are not open to researchers,” he said.

Fragoso said there had been an increased interest in the archives from the era by non-Catholic scholars, but researchers are still few in number.

“And the fact that they’re not Catholics many times results in an insufficient comprehension of religious terminology, leading to errors,” he said.

Fragoso admitted that the history of Brazilian slavery is complex.

He says the monastery’s documents show that slaves and monks lived in houses of the same quality. Slaves received medical treatment, were given incentives to create families, and were trained in different skilled trades.

“Some of the monastery’s slaves even owned slaves,” he said.

However, Franco stressed that slavery was always something violent.

“That’s the basic principle. To compare different situations inside the slavery system is not a good way of understanding it,” he said.

Vasconcelos said it is fundamental to revisit the issue of the Church’s role in the Brazilian slavery system.

“It has to bring a new attitude in the Church against racism. This confrontation with the past must generate not only an institutional mea culpa, but a prophetic attitude of the Catholics in regard to such problems,” he said.