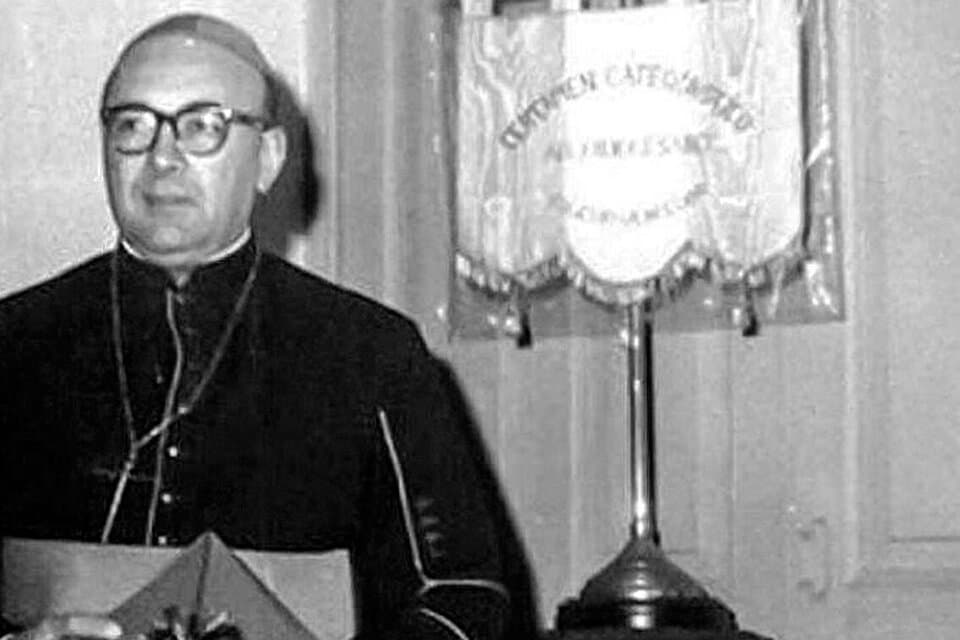

SÃO PAULO, Brazil –Argentina’s Church set up a committee to study the life and work of late Bishop Carlos Ponce de León, a renowned human rights defender whose tragic death in 1977, during the 1976-1983 military dictatorship, has been seen by many as a state-sponsored.

Along with Bishop Enrique Angelelli, killed by the regime in 1976 and beatified in 2019, and a handful of priests and nuns, Ponce de León has been considered by many Catholics as one of the dictatorship’s martyrs.

During a week of celebrations in his honor, organized in 2017 in the Diocese of San Nicolás de los Arroyos – in Buenos Aires province – which Ponce de León led for 11 years, Pope Francis sent a message saying the late bishop “didn’t negotiate the truth nor the Gospel’s tenderness.”

The Bishops’ Conference announced on May 8 that it formed a special committee, headed by Archbishop emeritus Jose Luis Mollaghan of Rosario, to examine the life and ministry of Ponce de León.

“For many of us, Bishop Ponce de León was a living signal of the Good Shepherd, giving his life for the Church in San Nicolás de los Arroyos, and in such a perspective he helps us as an example and as an intercessor before God,” the conference’s statement read.

The document said that archives and documents will be inspected and testimonies will be taken.

Father Luis Liberti, one of the researchers who worked on the three books of the study La verdad os hará libres (Truth will set you free) – a thorough analysis of the Argentinian Church’s actions between 1966-1983 – is a member of the committee.

The decision by the bishops came a couple of months after a high court decided to reopen the inquiry on Ponce de León’s death.

The ruling annulled the 1978 sentence that had considered the bishop’s death a traffic accident and had found the driver of the truck that hit Ponce de León’s vehicle, Luis Antonio Martinez, guilty of manslaughter, giving him a 6-month-long suspended sentence.

According to the case’s prosecutor, who had petitioned for its resumption in 2020, Ponce de León had been receiving several death threats in the months that preceded his death.

“He knew something like that would happen. He directly intervened and saved the lives of at least 31 people who were being persecuted by the regime,” Marisa Ponce de León, his niece, told Crux.

She was 20 when her uncle died and still can remember, almost 47 years later, that her father immediately thought it was a murder.

“My father, who was very close to his brother, knew everything about cars and about driving. When he heard the description of the ‘accident’, he said: ‘Carlos was killed’,” Marisa recalled.

Forty-five years later, an engineer simulated the crash between the two vehicles using computing and determined that it could not be an accident, she added.

Ponce de León told his brother many times that his letters were being censored by agents of the regime. Unidentified people would send him messages or call him saying: “We have already killed Angelelli. You’ll be gone by July.”

On one occasion, Marisa’s father was side by side with Ponce de León in his car when a truck crossed and almost hit them.

San Nicolás de los Arroyos was an industrial city, but had several slums. Ponce de León encouraged seminarians and priests to work in the poorest neighborhoods. They would soon be known as the local team of curas villeros – the slum priests. Nuns and lay people would also get involved in social issues by the bishop’s request.

“Due to all that, he was seen as a ‘red’ bishop. And many people in his diocese ended up being persecuted for their involvement with the poor. That was enough for the regime to call them communists,” Marisa said.

She told Crux a bishop has analyzed all Ponce de Leon’s homilies, public talks, and other documents and concluded that he was not connected to any political party or movement.

He was only worried about the poor and the Gospel, she added.

With the illegal detentions and kidnappings carried out by State agents, many families would ask for Ponce de León’s help. Even two of his nephews needed his assistance in order to get out of jail and escape from Argentina. His intervention enraged the dictatorship.

“Two men are responsible for his death. One of them died a few years ago, before justice was served. We’re struggling to get a response before the other one dies too. He is rather old now,” Marisa said.

Her father died in 1993, many years before the investigations were reopened for the first time, in 2004. Marisa said that during all her life she has been waiting for a conclusion for her uncle’s case.

“I’d like to see that man’s face. I’d like him to see our faces,” she said.

A canonical cause for Ponce de León’s beatification depends on the Justice’s definitions regarding his death, according to Marisa. But she was told by a vicar that Pope Francis has been strongly supporting the process.

Officially, the Argentinian Church is not talking about a beatification cause. Father Luis Liberti told Crux that he hasn’t met with his committee colleagues yet and that as far as he knows the work will not involve any canonical effort for Ponce de León’s beatification at this point.

“What I do know is that we will study about his life in order to keep his memory alive. I imagine I’ll be able to collect documents and pastoral letters and take testimonies from people who knew him,” Liberti said.

The priest said in the study about the Church and the Argentinian dictatorship, documents about Ponce de León emerged.

“A report of the Army intelligence had very strong words about the bishop and some Salesian priests. It had been issued by a lieutenant-colonel of San Nicolás,” he said.

Marisa said that her family learned over the years to separate the juridical sphere, in which her uncle’s case still waits for justice, from the Church’s processes involving his legacy. There’s also her personal take on a man that was part of her family and would always come to visit.

“As his niece, I’ve never seen him as a holy man. I saw him as a bishop who would roll up his sleeves and work with the poor,” she said.

She hopes, however, he can be canonized someday.