SÃO PAULO – A new and largely unpredented “Catholic bloc” in the Senate in Brazil, the largest Catholic country on earth, has been presented by its founders as a way to defend Catholic “moral and ethical values,” but denounced by critics as unrepresentative of the wider Church.

Officially launched on Sept. 4, the bloc is seen by many observers as an attempt by Catholic legislators to replicate the success of Brazil’s “Evangelical Caucus” in parliament and among govenrment officials, which, were it a formal political party, would be the third largest in the country.

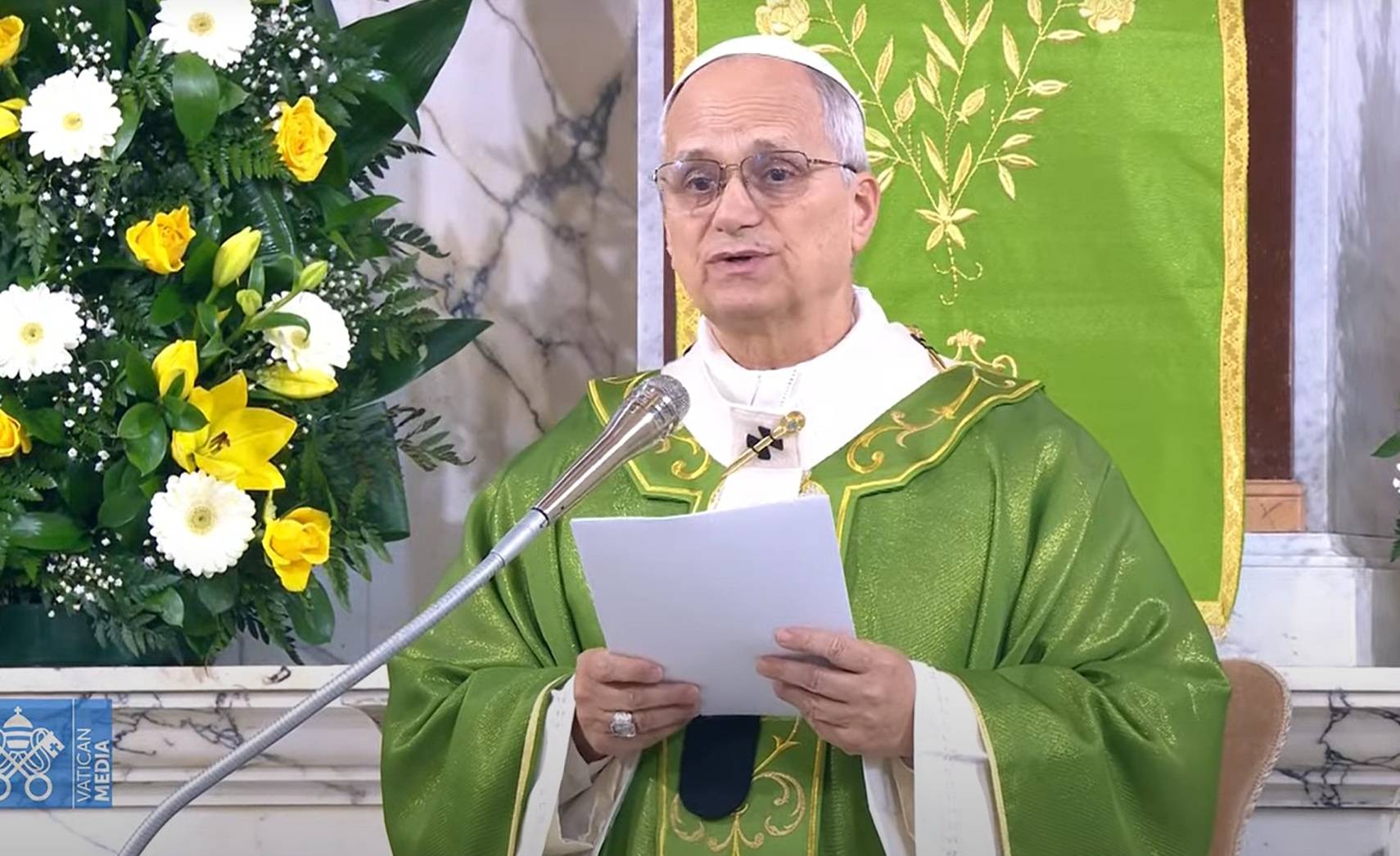

Notably, although some Brazilian bishops attended the Sept. 4 launch event, inlcuding Cardinal Paulo Cezar Costa of the national capital Brasilia, the country’s bishops conference has said it was not consulated about the initiative and has no ties to it.

The Catholic bloc was founded by Senator Marcos Pontes, a military officer who in 2006 visited the International Space Station and became the first – and, until now, the only – Brazilian astronaut.

Pontes was the Minister of Science, Technology, and Innovation during President Jair Bolsonaro’s government, and was elected a senator in 2022. He’s a member of Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party and is an advocate of the former president’s conservative agenda.

The new bloc’s vice president is senator Flávio Arns, a long-time progressive politician whose notoriety at the beginning of his career was due to the fact that he was Cardinal Paulo Evaristo Arns’s – and his sister Zilda’s – nephew.

Arns was the Archbishop of São Paulo and a famous human rights advocate in Brazil. Zilda was a physician who founded the Children’s Pastoral, a major church initiative that has been fundamental in helping thousands of poor mothers and their babies.

Ten other senators are part of the bloc, including Espiridião Amin, a right-wing strongman in Santa Catarina state’s politics who has been active since the years of the military dictatorship (1964-1985). Amin supported the regime and has always been faithful to the same political group, which is often at odds with the social agenda of the bishops’ conference.

The bloc announced that its mission is to “defend the ethical, moral and doctrinal principles advocated” by the Church; to “monitor bills of interest” of the bloc in the National Congress; and “to advise senators in the preparation and voting of bills” that have the same goals of the bloc.

One of the participants in the Sept. 4 ceremony was Congressman Eros Biondini, a Charismatic Catholic Renewal activist and singer. Biondini headed the Chamber of Deputies’s Catholic bloc till the beginning of 2024 and is still its vice president.

Mentioning the need to struggle for policies that are in line with Catholic beliefs, Biondini’s speech revealed one of the Catholic congressmembers’ concerns.

“The government should take care of all drug addicts and never think, instead of it, about the liberalization or the [defense] of drugs,” he said.

In Brazil, so-called “therapeutic communities,” most run by churches (especially by Evangelical denominations, but also by Catholic groups), have been an important alternative to deal with drug addiction. Addicts are sent to those places, many times in rural areas, where they work and are expected to go “cold turkey” in terms of drug use.

Some healthcare experts and government officials argue that the therapeutic communities have never proven to be effective. At the same time, critics say, thet also violate the rights of addicts, inpart by compelling them to take part in religious activities. A recent survey showed that in 89 percent of these communities, reading the Bible is a mandatory practice, as well as attending religious ceremonies.

The communities were promoted during the Bolsonaro administration, which funded them with public money. Liberal President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva initially continued to send funds, but the opposition of members of his government and of physicians and scholars to such a policy led him to cut the money off earlier this year.

Critics of the therapeutic communities insist that public funds should go only to government-administered clinics, where addicts receive daily treatment.

According to theologian Fernando Altemeyer Jr., a religion studies professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, securing government money for initiatices such as the therapauetic communities is the real aim of the new Catholic bloc.

“With the excuse of creating a bloc to dispute forces with the Evangelical bloc, those politicians will ask money for Catholic groups and parishes and try to obtain radio and TV stations’ licenses for the church,” Altemeyer told Crux.

In his opinion, members of the Catholic bloc want to appear as “leaders of faith” with electoral and political goals.

“That group is really unnecessary. Most of them are connected to the far-right and are not different from the members of the Evangelical bloc,” he said.

In Altemeyer’s opinion, there is no room for such forces in Brazilian democracy, “in which a multiplicity of parties debate the society’s themes with the adequate pluralism.”

“They shouldn’t say they are the ‘Catholic bloc.’ They are only a fraction of the Catholic Church in Brazil. They don’t have permission to represent all Catholics,” Altemeyer said.

Daniel Seidel, who heads the bishops’ conference’s Justice and Peace Commission, told Crux that “it’s not part of the conference’s tradition to incentivize the formation of blocs in Congress.”

“To make things even worse, most of those politicians support policies that go against the bishops’ conference’s guidance,” Seidel said.

Many congressmembers that are part of the Catholic bloc in the Chamber of Deputies, for instance, support the reduction of the minimum penal age (which is 18 in Brazil), while the episcopate is against it. Many also supported a major labor reform that was promoted in 2017 and, in the view of the bishops, redcued the rights of Brazilian workers.

“That so-called Catholic bloc is coherent with which Catholic stance, if it doesn’t follow the episcopate’s views?” Seidel asked.

In his opinion, the new bloc in the Senate, as well as an existing one in the Chamber of Deputies, are linked with a limited “moralistic agenda” that only includes topics such as abortion and euthanasia.

“The bishops’ conference has always worked in favor of life and resorted to wide discussions with politicians to do so. It doesn’t have corporate interests,” Seidel said.