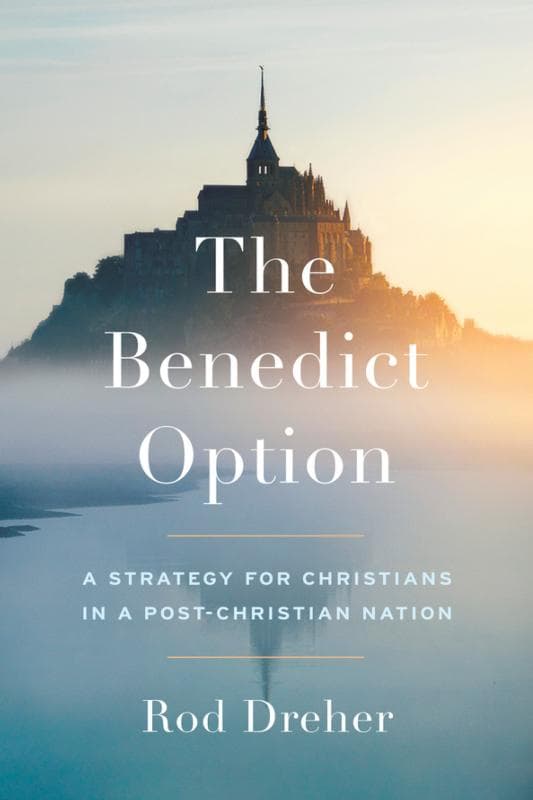

[Editor’s Note: Michael Baxter teaches Religious Studies and Catholic Studies at Regis University in Denver. He was the co-founder of two Catholic Worker communities in which he lived and worked, Andre House in Phoenix (1984-88) and the Peter Claver Catholic Worker in South Bend, Indiana (2003-2009). He also served as director of the Catholic Peace Fellowship from 2001-2012. He speaks to Charles Camosy about The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation, in which Rod Dreher proposes that serious Christians can “no longer live business-as-usual lives in America,” and “that we have to develop creative, communal solutions to help us hold on to our faith and our values in a word growing ever more hostile to them.”]

Camosy: Do you agree with Dreher’s diagnosis?

Baxter: Yes and no.

Yes, I agree that mainstream U.S. culture is largely un-Christian, and that the government imposes secular values and mentality on supposedly independent bodies, including churches.

But no, I don’t agree that this all came to a head in 2015 with the Indiana religious freedom statue being rescinded and then the Supreme Court decision affirming the right for gays to marry. Dreher sees 2015 and gay marriage as the point of no return. I don’t see it that way.

How do you see it?

Christians should be as troubled, indeed more troubled, by war, poverty, racism in the United States than Dreher seems to be. Writing as a “conservative Christian,” as a “values voter,” as he calls himself at one point, Dreher’s timeline and plotline are warped accordingly.

He refers to the 1960s as a time of consensus, except civil rights, as if the Vietnam War ever happened or wasn’t a concern for Christians. He mentions the Reagan years as if it was a highpoint in U.S. politics: The good ole days of nuclear terror, the Iran Contra scandal, and civil war in El Salvador, with U.S. funds ($1,000,000 a day) being diverted to the death squads.

How would you rewrite the timeline?

One point of no return would be firebombing German and Japanese cities in World War II, followed by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Another, earlier point of no return would be the U.S. entering into the wholesale human catastrophe we call World War I.

But in reality, I don’t think there was a time when America was Christian and thus I don’t think of this story in terms of decline, falling away, losing the Christian values “we” once cherished. The United States was founded as a slave nation. It was “settled” by massacring the peoples living on the land or relocating them, deporting them from what was their homeland.

Dreher writes as if America and Christianity lived together harmoniously at one time, as in a marriage; but now, he thinks, America, the nation, the country, has filed for divorce. I don’t think that, theologically, morally, the two were ever really married.

So what we’re recognizing now is not a divorce between church and nation, but an annulment. The marriage never really existed.

So what do you think about Dreher’s prescription, the Benedict Option?

It’s hard to argue with the initiatives Dreher is pushing for: A stronger, more vibrant sense of discipleship; churches ready and willing to suffer for the Faith; an anti-political politics, as an alternative to conventional culture-war politics; a more robust form of Christian commitment shaping how we live, how we marry and raise families, how we educate our children and young adults and adults, how we deal with the ever expanding regime of technology.

If Dreher gets his audiences to think seriously and imaginatively about these things, that’s a good thing. If he gets people reading Christian Smith, Neil Postman, and Wendell Berry, three authors whom he relies on in the book, that’ll be a good thing too.

Not to mention getting his audiences to read After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre, right?

Yes, but Dreher’s use of that book is flawed. After Virtue must be understood in the context of MacIntyre’s Marxist-informed critique of advanced capitalism and the modern state.

One key feature of capitalist culture, he argues, is that we cannot move beyond conceptualizing ethical stances as of individual choice or preference, a position he calls emotivism. This is why political disputes never get settled.

The state claims to be the guarantor of individual rights and liberties and adjudicator of conflicting interests, all the while protecting economic inequality and state-sponsored violence. Dreher repeats MacIntyre’s critique of emotivism, but without the searing critique of market capitalism and the modern state, which surely would have lost the sympathy of his “conservative Christian” readership.

Moreover, Dreher, perhaps owing to his Evangelical roots, presents his solution to our problems as a matter of choice for individuals, small groups, or churches. He thinks in terms of dramatic decisions, options.

By contrast, MacIntyre, both as an Aristotelian and a partial subscriber to Marxism, thinks in terms of virtues, traditions, and communally-constituted modes of reasoning over long periods of time. Thus, his reference to “another St. Benedict” is not so much to the person but to the form of life that evolved over centuries in his name, a form of life that transformed political, economic, and social relations in a way that resisted the feudal order of the Middle Ages.

In this sense, MacIntyre was in no way talking about withdrawal from society but social transformation, a transformation extending beyond any one person’s or one community’s intention or option.

This book has stirred up a lot talk about what option the churches should take these days.

It has. Now we hear of the Francis Option, the Dominic Option, the Sophia Option. Not long ago, on the web, I came across a proposed “Murray Option” (referring to the American Jesuit theologian, John Courtney Murray). I was afraid that this would happen.

Afraid? Why?

Dreher’s argument will surely generate—indeed it already has—a counter-reaction calling for a “public theology” designed to bolster the public life of the nation.

There’ll be conservative and liberal versions, each arguing in different ways that the United States has reached a crisis point and that it is irresponsible to opt out of the public debate now.

It will intensify as we approach the 2020 elections, and the result will be another round of politically partisan culture wars. Our collective political life resembles hamsters running in a cage, scurrying in order to stay in the same place.

I should stress that Dreher is right to urge Christians to free themselves from this kind of partisan politics. But it will be difficult.

The state weighs heavily on our minds, our imaginations. It is hard to unthink the necessity of the state and to reimagine society in a new way.

This is why the most important point in the closing paragraph in After Virtue is that the barbarians are not waiting on the frontiers but have been governing us for quite some time. The fact is that we do not see this is the problem.

So can anything be done?

Live and work for the common good on the local level. Resist the corrosive effects of the state and the market. The best parts of Dreher’s book are the examples of people living differently.

A lot of people have been living creatively and concretely for quite a while, not out of fear of assimilation into the mainstream, but out of love of God and pursuit of the good life, the gospel and the natural law.

On this score, one example he might have included is Dorothy Day, herself a Benedictine Oblate, and her mentor, Peter Maurin, whose easy essays set forth a plan, not for withdrawal, but for social reconstruction, building a new society within the shell of the old.