DENVER — “I’m terrible at art,” Katie Fosselius says with a laugh, describing an art collaborative program she helped to start at the Denver Rescue Mission, insisting “I’m more the entertainment!”

Fosselius has a Masters in social work, and served in a variety of settings before leaving the world of paid employment to raise three daughters. Once she was able to volunteer her time again, she knew the population she wanted to focus on. In fact, she’s known since she was a child.

People often turn away from the growing homeless population, and legislatures pass laws against panhandling, but Fosselius “enjoy(s) the true street aspect.”

She went to her first meal service in 7th grade, and since then has wanted to work in service to the poor and homeless. She remembers being surprised at learning how few people want to volunteer with this population. She had thought, “as Christians we all want to do this.”

For her, it comes naturally.

She’s dealt with an anxiety disorder since she was 18, and believes her own experience has helped her to “feel great empathy for their struggles, because in many ways I get it, the difference being I have a home and a strong support system to rely on.”

As a Catholic very inspired by her faith, it seems a bit surprising that Fosselius found what she calls “her family” at Denver Rescue Mission, a non-denominational Christian organization. She’s volunteered with Samaritan House, a shelter run by Catholic Charities in Denver, but she was getting stretched too thin, doing too many things.

In addition to her other commitments, she studies theology at the local Augustine Institute.

She says her involvement with the mission, “was serendipitous. I feel that God meant for me to be here. Everything evolved so smoothly here. I just love it here.” And the kicker, “they wanted me.”

Blending a theology degree with her social work education and experience she thinks she might find happiness eventually as a spiritual director. However, she’s realistic in her road back to work as she jokes, “hard to know what actual employment would look like.”

But her love of the social spiritual realm will definitely guide her path in helping people off the street find community.

Fosselius started volunteering in the kitchen when she first arrived at the mission, but says that there wasn’t enough interaction with the guests. She says her time in the kitchen was cathartic, but they were going through the line so quickly, she barely had a chance to say hello. She knew she wanted to do something more intimate.

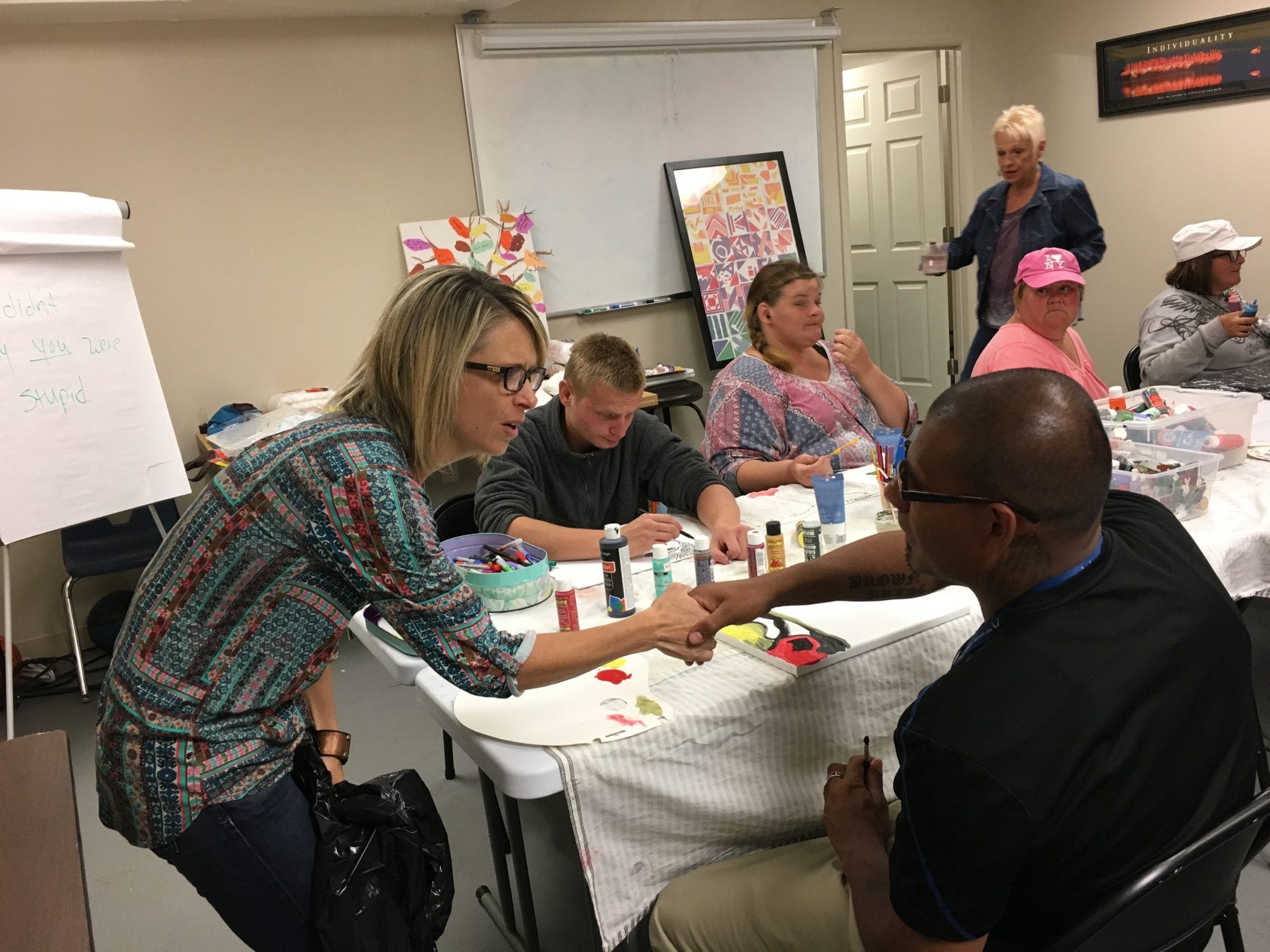

So she started proposing things that would put her in closer contact with people. She teamed up with Angie Tims, the Care Coordinator at the mission, and in the fall of 2015 they began what would become the art collaborative with a flower arranging project for Thanksgiving.

Fosselius says the funny thing was that it’s “mostly men here, but they loved flower arranging.”

She was also able to start a knitting group, and true to form says, “I’m a terrible knitter!” The biggest difficulty with a project like knitting is that it takes time to teach and learn. The biggest problem is that the people coming through are transient, so things were started that would never be finished. Painting and smaller art projects are more conducive to the situation.

An announcement is made to everyone over a loudspeaker that the art class will be starting soon and all are welcome. However, it takes place in the basement so people have to follow a rather circuitous route to find the room. Many who might want to participate never make it.

So, Fosselius moves around the courtyard where people are sitting and chatting to encourage, or as she says “harass” people to come down and join in. One woman tells her she’ll come “as long as it’s not all ‘Christiany.’” Katie laughs and tells her not to worry.

The day’s project is simple on its face. Fosselius provides everyone with t-shirts and tie dye, and who doesn’t like tie dye? She suggests they play some music from the 70s to get in the groove and is quickly obliged. The room falls to the task happily all while singing. It’s the community she craves with the intimacy and easy back and forth between the guests and her.

She makes a point of introducing herself to people she hasn’t met before or people who come for a second time trying to encourage them. People talk and laugh, and Katie is patient and full of compliments.

(Meanwhile, as an official employee, Tims has to run around trying to make sure the dye isn’t getting everywhere, which of course it is. The mission is now in possession of some colorfully tie-dyed tables.)

The real worry with this project for Fosselius is that because time is needed for washing and drying the shirts, some of the people won’t be back to see and collect their finished shirt. But it’s a problem she accepts, because she has to. She is planning to take all the shirts to her house, wash and dry them, and return next week. The fear some of the people won’t be back is balanced by her hope that they will.

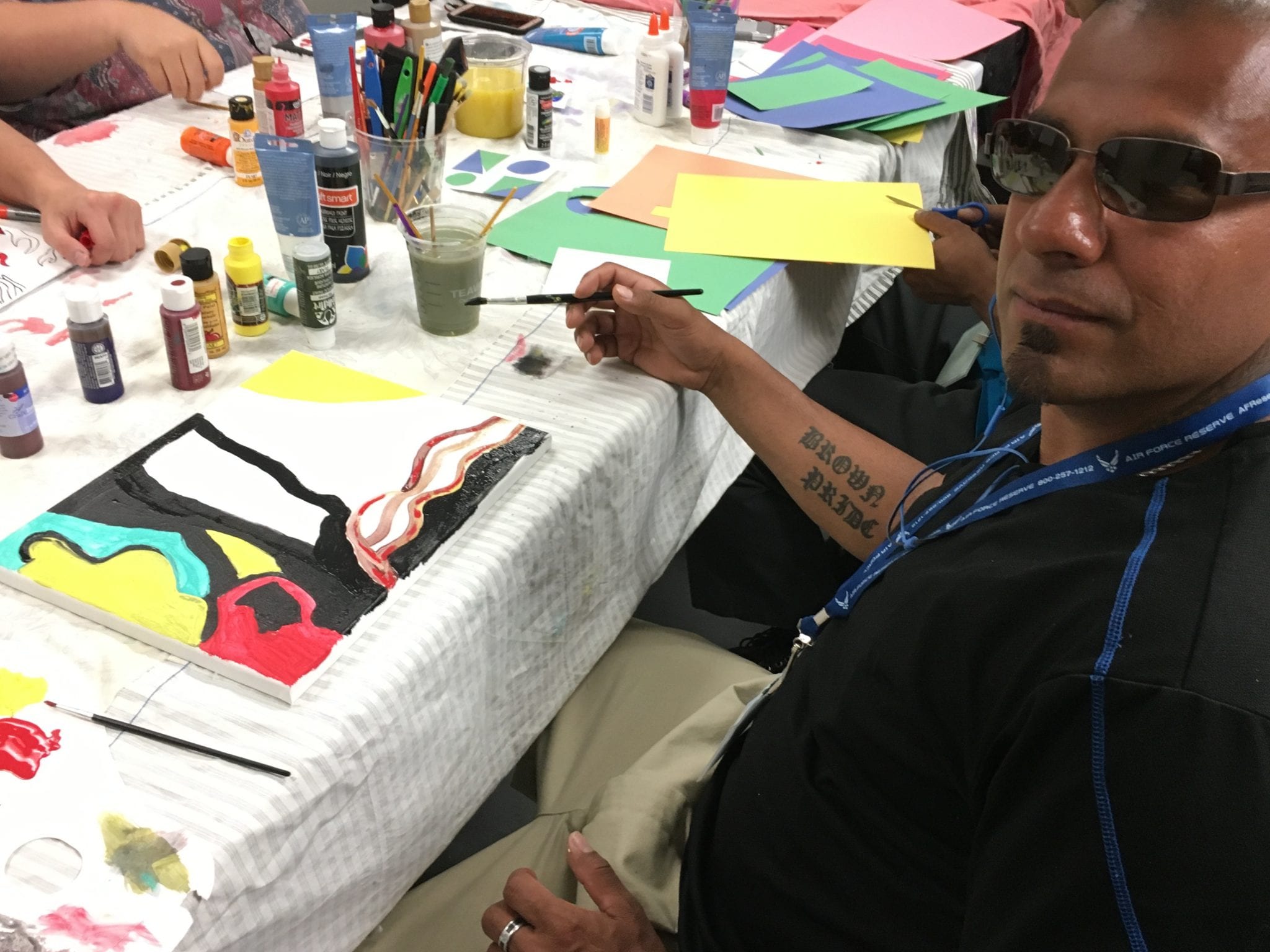

The project doesn’t take as long as she expected, but like anyone who’s ever created a lesson plan for a class, Fosselius and Tims have an old project ready to go for when people finish their shirts. They are working towards an art exhibit, so they have other projects on hand.

There’s no criteria for what will go in the show, because as Fosselius says, this is their heart and soul and no matter the level, the important thing is that they “always show heart.”

They hope that the show will bring an awareness that DRM is a big organization, and this program exists and has its own life. They want the greater community to see how beneficial the art is to people’s soul. Fosselius says the art is an expression of our love of God and our creation.

One might think the culmination of the art collaborative into an actual show would be the thing Fosselius considers one of her biggest successes. While she’s excited for the show to happen, and sees all the positives for people getting to see their art showcased, she says her greatest success is the community the collaborative creates.

Just having people singing together and laughing together is the thing she most relishes. When people say to her ‘this was such a relief,’ or ‘this made my day,’ or ‘I was stressed and now I’m less stressed,’ she is fulfilling her mission. Many people have told her, ‘this gives me a break from the street,’ and that’s what makes her day.

When asked if she ever thinks there have been failures, she doesn’t say anything about a particular project gone awry, but rather thinks of times when she walked away from someone and wonders later if she should have stayed longer and prayed with that person.

As a social worker, she’s always questioning if she’s done everything she could have.

So for a person such as Fosselius, who gives her time freely to build community for people others avoid, the “Christiany” in the collaborative doesn’t have to be in-your-face, because it’s inevitably and inextricably at the basis of it all.