DURHAM, North Carolina — Five hundred years ago this week, Martin Luther is said to have nailed his 95 theses to the door of Wittenberg, Germany’s Castle Church, ushering in a revolt against the Roman Catholic Church.

The ensuing theological demolition also involved its artwork, much of which was defaced or burned in now-Protestant areas of Europe.

On the turf it managed to hold, the church mounted a response — the Counter-Reformation, a multi-pronged movement responding to and resisting the reforms.

It, too, had an artistic aspect: Titian, El Greco and Caravaggio. But also Carlo Dolci of Florence, Italy, whose meticulous paintings of Christian themes, saturated with emotion and glistening with color, were everything the iconoclast reformers railed against.

Dolci (1616-1687) is finally getting his due, with a solo show — his first in the U.S. — at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. (It was shown earlier this year at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College.)

The deeply Catholic Baroque master, a favorite of the Medici banking dynasty, is considered one of the finest Italian painters of the 17th century. His works are also a reminder of a visual vocabulary of Catholic art many modern viewers no longer recognize.

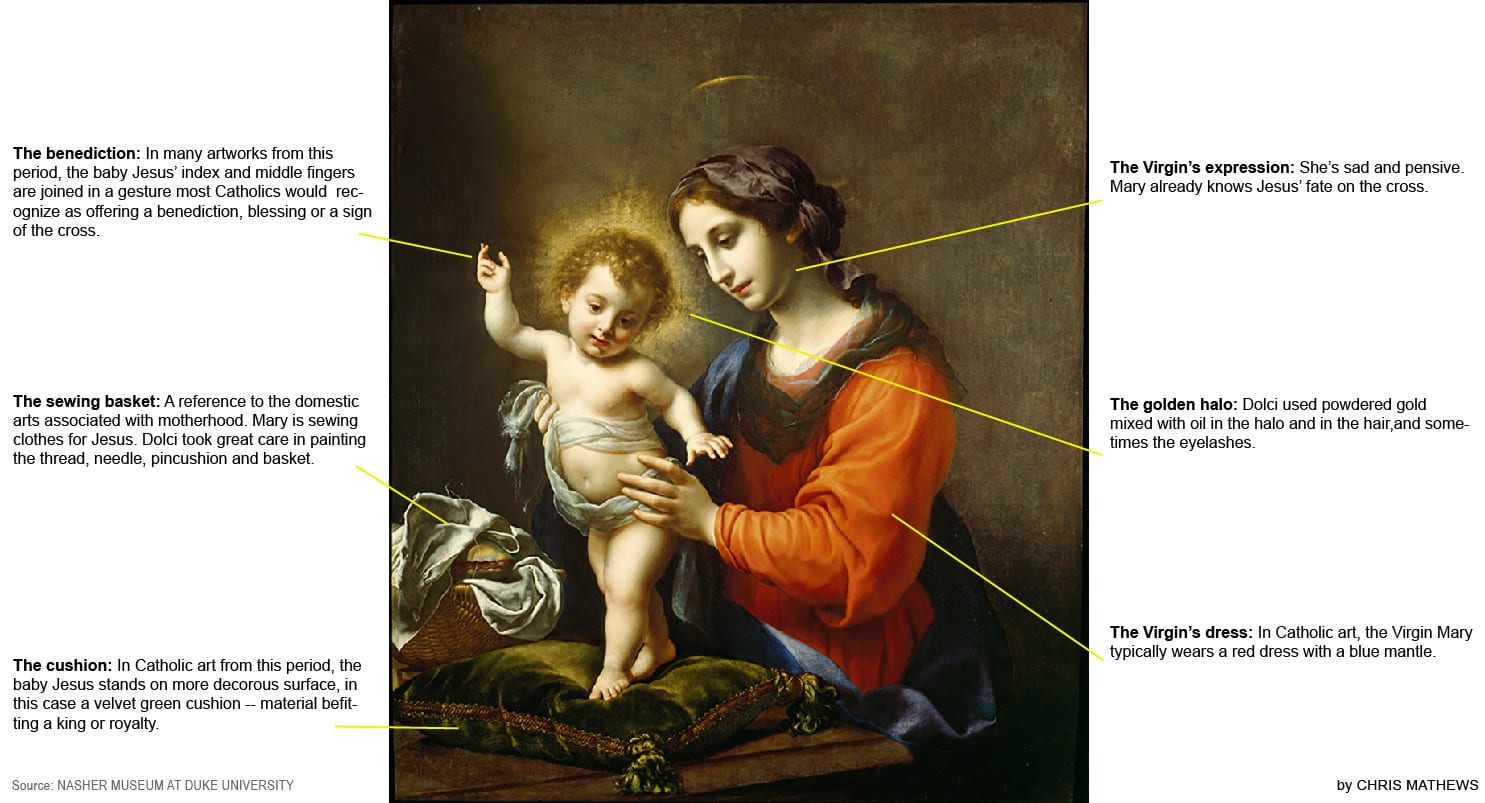

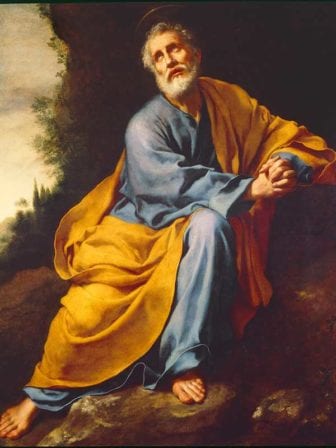

Rarely was the iconography of defiantly Catholic belief so meticulously and self-consciously rendered. Here, tender and otherworldly subjects wrapped in religious ecstasy gaze toward heaven; the baby Jesus’ two fingers meet to form a benediction; the Virgin Mary’s eyes betray her sorrow; the disciple Peter sheds a tear for denying Jesus; the angel Gabriel crosses his hands over his chest as he delivers his message.

Dolci’s paintings are libraries of the day’s Catholic visual conventions:

- Mary Magdalene is portrayed with wild, curly locks and a jar of oil next to her. (In some accounts, Magdalene is the “sinful woman” who anoints Jesus’ feet, though many scholars say this was not Mary Magdalene.)

- John the Baptist is typically portrayed carrying a cross made of reeds on which hangs a banner with the Latin phrase “Ecce agnus dei,” or “Behold the Lamb of God.” (John, according to tradition, preached about the one who is to come who is mightier than he.)

- Matthew, the author of the first Gospel in the New Testament, is represented writing with a quill while an angel hovers in the background. (Matthew’s symbol is an angel, while Mark is represented by a lion, Luke an ox, and John an eagle.)

These devices were not new with Dolci. They were the deposit of hundreds of years of accumulated symbolism. But he upheld them with a controlled virtuosity.

He was admired for his exacting attention to detail, for example in the red ringlets that drape the side of the angel Gabriel’s face, or in St. Appollonia’s left thumb pressing into her chest while she holds a pliers with one of her extracted teeth in her right hand. (According to legend, all her teeth were pulled out before she was killed.)

“These images were created for a specific time and place where Catholicism was the prevailing religion,” said Eve Straussman-Pflanzer, who curated the show and now heads the European Art Department at the Detroit Institute of Arts. “Art had a real role to play in society, and in a largely illiterate society, that was really the visual vocabulary.”

Dolci’s generation of Catholic artists assured that the language survived while the faith was under attack elsewhere.

“Carlino,” as he was often called because he was short but also shy, began painting at age 9 in the workshop of another Florentine artist. Following his teacher, he joined a lay confraternity, or brotherhood, devoted to St. Benedict. According to his biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, Dolci was said to utter, “ora pro nobis,” Latin for “pray for us” in between each brushstroke. He also wrote prayers and other religious sayings on the backs of his canvases.

“For Dolci, the act of painting was an act of prayer and devotion,” said Sarah Schroth, the Nasher’s director. “The way he pictured the divine figures was very well thought out religiously.”

He eschewed formats like altarpieces and frescoes in favor of portraits of faith so arresting and intimate they could be used as an aid to prayer and a reminder of God’s creation, Schroth added.

The Medicis loved them and commissioned Dolci to paint multiple versions for their bedrooms and oratories, or private chapels.

He has subsequently been collected by the world’s great museums; and the 50 paintings on view here come from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

But such honors have not come without struggle. In their zeal to scrub churches of devotional artwork and especially images of saints, the Protestant reformers found Dolci’s works distasteful.

Later art historians and critics found his works “affected” “cloying,” or excessively, “sweet.” (“Dolce,” spelled with an “e,” actually means “sweet” in Italian.)

But others liked what they saw. Thomas Jefferson encountered the master’s paintings while traveling abroad. The deist Anglican, who might have been expected to hate Dolci’s work, wrote a friend that the painter was a “violent favorite.”

One arena in which Dolci’s artistic conventions have never gone out of style is the market for mass-produced Catholic devotional items, such as saint prayer cards handed out at churches and images of Jesus, Mary or the saints glued to candle jars.

Beyond that niche, Straussman-Pflanzer said, much of the artist’s iconic symbolism may be lost on today’s viewers, more literate in pop culture than religious imagery.

But at least one group taking in the exhibit in October showed that Dolci can still be very much appreciated. Members of a tour group of Catholic students, accompanied by Father Michael Martin, the Catholic chaplain at Duke University, gazed reverently on the works, pausing to recite short prayers before some of the paintings.

Emma Miller, director of communication for the Duke Catholic Center, said the Dolci tour had all the emotional weight of the Stations of the Cross, the pre-Easter ritual in which Catholics reenact Jesus’ steps on his way to the cross.

“It felt like I was walking through different points in the Catholic tradition,” she said. “A little mini-pilgrimage with your feet.”

(“The Medici’s Painter Carlo Dolci and 17th-Century Florence” is on view until Jan. 14, 2018.)