BOSTON — The extra day we get approximately once every four years is a way to adapt the calendar year to the astronomical year.

But did you know the present system of calculating the leap years was designed around fixing the date of Easter?

While the concept of the leap year has been around since ancient times — the ancient Jewish calendar added a leap month every 19 years for example — the current calendar year has its origins in the Catholic Church.

According to Father James Weiss, an Episcopalian priest and associate professor of church history at Boston College, in 1582 Pope Gregory XIII set about adjusting the calendar to bring the celebration of Easter to the time of year it was celebrated when it was introduced by the early church.

The Julian calendar — used by the Roman Empire and named after Julius Caesar — had followed the ancient Egyptian calendar and added an extra day every four years. However, Weiss explained, that was not in keeping with the astronomical calendar.

“Once every four years proved to be too many leap years, and over time, the calendar year did not match the astronomical year,” he told The Pilot, newspaper of the Boston Archdiocese.

Pope Gregory determined the calendar was out of sync with the spring equinox by 10 days. This was significant to the church because the date of Easter was set by the Council of Nicea in 325 as the Sunday after the first full moon of spring, and the start of spring was fixed as March 21. Without adjustment, the date of Easter would eventually drift into the summer.

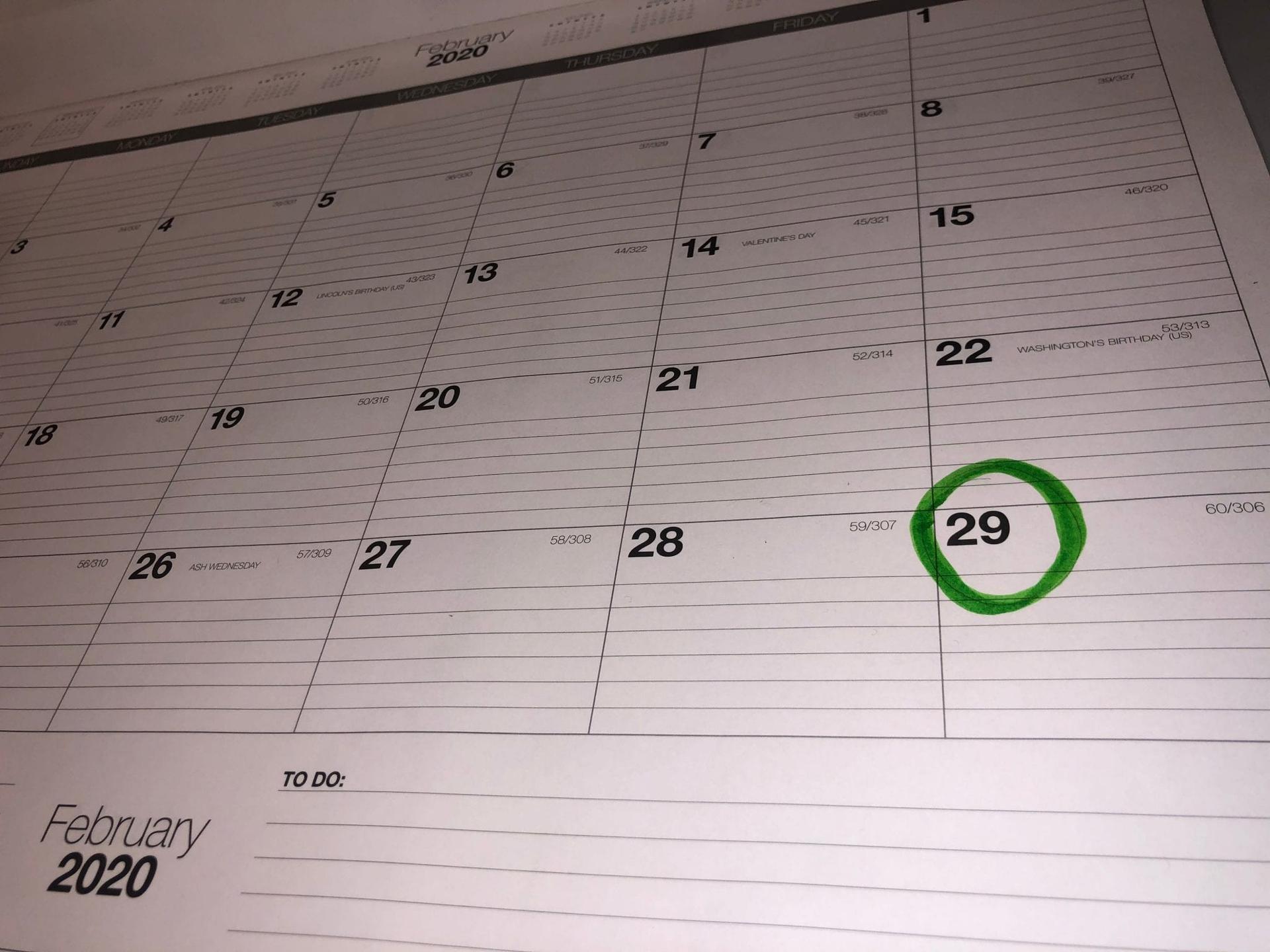

So, on Feb. 24, 1582, Pope Gregory issued a papal bull titled “Inter gravissimas” in which he set about to correct the error. The new calendar — which would be called the Gregorian calendar — added an extra day to February every four years, unless the year is divisible by 100. Those years do not have a leap year. The exception to that rule is if the year is divisible by 400. So, following this rule, 1900 was not a leap year, but 2000 was.

Although this mathematically corrected the problem, Weiss continued, there was the problem of the 10 days that were “out of sync.” Catholic countries such as Italy, Spain and Poland, he said, altered their calendars during the month of October, so that when people went to sleep Oct. 4, they awoke on what was then Oct. 15.

“To complicate matters, not all of Europe followed the Gregorian calendar,” Weiss continued. “There was a huge confusion for a very long time with regards to the date, which introduced a kind of chaos into European dating.”

Over the next 200 years, most European nations adopted the Gregorian calendar, he continued. The final country to switch to the Gregorian calendar was Turkey, which finally adopted the calendar in 1927.

Today, most of the world uses the Gregorian calendar. Some exceptions, such as Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Afghanistan still use their traditional calendars to mark the years. Others, such as India, Bangladesh and Israel use both the Gregorian and their traditional calendars to mark the passage of time.

Tracy is a contributor to The Pilot, archdiocesan newspaper of Boston.

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.