Against the backdrop of a pandemic’s blight and wounds from an acrimonious election, a group of acclaimed actors on Sunday staged an online reading of a religious text with remarkable relevance to the current moment: the Book of Job.

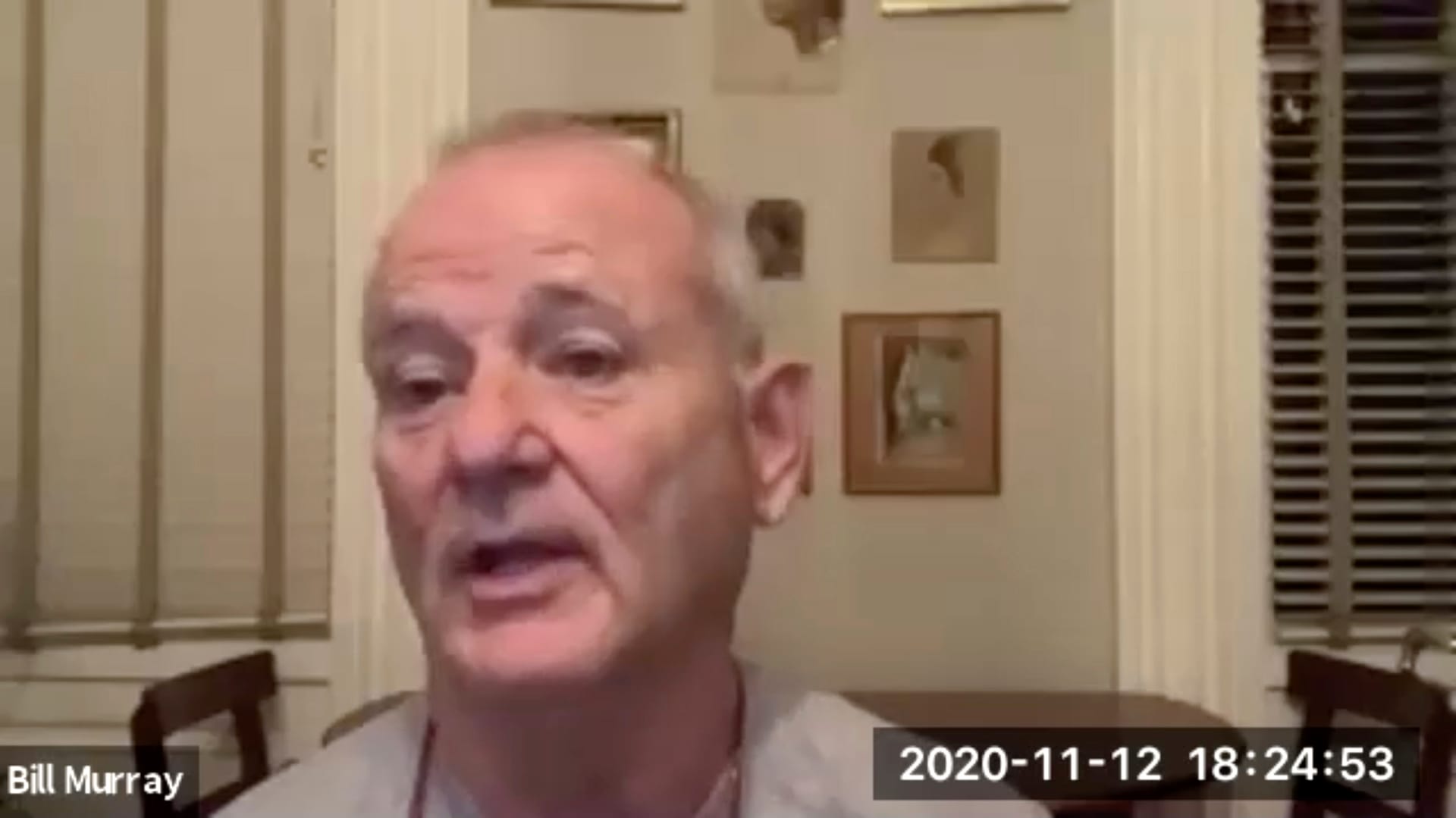

Audience members may have been drawn to the production by the casting of Bill Murray as Job, the righteous man tested by the loss of his health, home and children, but the real star was the format. Staged on Zoom, it was aimed at Republican-leaning Knox County, Ohio, with participation from locals including people of faith, and designed to spark meaningful conversations across spiritual and political divides.

After the performance, several people from the area were asked to share their perspective on the ancient story in a virtual discussion. It was then thrown open to some of the scores of others signed in, no matter their location. One young woman studying social work shared that Job’s judgment at the hands of others during his suffering inspired her to reflect on “how I am practicing empathy” during the coronavirus.

The structure of a dramatic reading followed by open-ended dialogue is a fixture of Theater of War Productions, the company behind the event. Artistic director Bryan Doerries is an alumnus of Kenyon College in Knox County and chose the area to focus on bridging rifts opened by the election and sharing the pain of a pandemic that’s tied to more than 275,000 U.S. deaths.

By using Job’s story “as a vocabulary for a conversation, the hope is that we can actually engender connection, healing,” Doerries said. “People can hear each other’s truths even if they don’t agree with them.”

The performance was headlined by Murray and featured other noted actors such as Frankie Faison and David Strathairn. The cast also included Matthew Starr, mayor of the Knox County town of Mount Vernon, who will play Job’s accuser. He said the timing is perfect for the moment the country is going through, between the pandemic, the heated election and racial justice protests.

His hope is that the event and the dialogue afterward lead to less shouting and more listening. And a good story like that of Job can do so more effectively than a new law or a new directive, by changing people’s hearts, said Starr, a Republican and supporter of President Donald Trump who founded an independent film company before going into politics.

“God does not say that bad things aren’t going to happen, but He does tell us, when they do, we’re not alone,” Starr said.

Knox County, a largely rural community of about 62,000 residents including a medium-size Amish population, lies about an hour east of the state capital, Columbus. Despite its numerous farms, most people in the county work blue-collar manufacturing jobs at several local factories.

The county, which is 97 percent white, is a conservative stronghold that voted for Trump by a nearly 3-1 margin in November and also went overwhelmingly for him in 2016.

An exception is Kenyon College, a small liberal arts school perched on a hill a few miles outside Mount Vernon. Voters in the precincts comprising the college and the village of Gambier voted 8-1 for President-elect Joe Biden.

To help prompt more locals to engage in the post-reading conversation, Doerries worked with leaders from multiple faith traditions. Among them is Marc Bragin, Jewish chaplain at Kenyon, who said he hopes the experience can help people who share bigger values look beyond their differences.

Bragin, administrator of a project backed by the nonprofit Interfaith Youth Core that partners Kenyon students with counterparts at nearby Mount Vernon Nazarene University, said he’s hopeful they will attend the discussion and take away an important lesson: “Surround yourself with people who aren’t like you,” he said, “and you can have such a bigger impact on your community, your world.”

Pastor LJ Harry, who has also been recruiting people for the virtual conversation, does not believe Knox County is as divided as other places in the country. The police chaplain and pastor at the Apostolic Church of Christ in Mount Vernon said most in the area are united in their support for Trump and for law enforcement, with protests after the death of George Floyd spirited but peaceful.

Harry said the community’s biggest point of contention is over mask-wearing, with many resisting Republican Gov. Mike DeWine’s statewide mandate. He likened Knox County’s need for healing to that of a hospital patient who has left intensive care but remains in a step-down unit, and said he hopes the performance will drive home God’s central role in Job’s story.

“That’s the message I’m hoping our church family, our community, hears,” Harry said. “God has this in control, even though it feels like it’s out of control.”

In the biblical tale, God allows for Job’s massive losses as a means to share broader truths about suffering. The story ends with the restoration of what was taken from him, plus more.

Theater of War held its first Job reading in Joplin, Missouri, a year after a tornado killed more than 160 people there in 2011. The company has performed more than 1,700 readings worldwide, harnessing Greek drama and other resonant texts to evoke deeper dialogues about an array of issues.

Doerries acknowledged that his company’s readings always have the potential to fall flat if a genuine back-and-forth doesn’t develop. Still, he’s betting that Sunday’s event could create space for people from different backgrounds, in Ohio and beyond, to engage with each other.

“Our hope is not that there’s going to be a group hug at the end of the thing, or that we’re going to resolve all our political differences, but that we can remind people of our basic humanity … what it requires to live up to basic values such as treating our neighbor as ourselves,” Doerries said.