ORLANDO, Florida — The independent drama Roe v. Wade had its red-carpet premiere, billed as the first large-scale movie opening since the pandemic began, on Feb. 26 at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando.

The event at last allowed viewers to evaluate for themselves this decidedly pro-life production dramatizing the 1973 Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion across the United States. Like that landmark ruling, the film has — predictably — been the subject of much controversy.

Co-director Nick Loeb welcomed a socially distanced crowd that filled the majority of the Hyatt Regency Hotel’s expansive conference hall. Introductory remarks also came from Fox News political commentator Tomi Lahren, who had a cameo in the movie.

Meanwhile, high-profile advocates such as Father Frank Pavone, national director of Priests for Life, and Emily Berning, president and co-founder of the charity Let Them Live, posed for the cameras.

As is the case with many a finished feature, the warm reception accorded Roe v. Wade at CPAC belied the movie’s arduous birth pangs. In this case, though, those travails were more political than cinematic. Loeb, for instance, has accused Facebook of denying his efforts to raise funds on its platform because of his movie’s agenda.

Subsequently, Salon and the Daily Beast opened fire on the production, questioning the script’s veracity and reporting that crew members — including the director — were storming off the set in protest, “shocked by the extremity of (the film’s) point of view.” That left Loeb and co-producer Cathy Allyn, with whom he collaborated on the screenplay, to direct Roe v. Wade themselves.

In his riposte to this negative publicity, in an in-depth interview The Hollywood Reporter published in late February, Loeb maintains that he intended to do justice to both sides in what is arguably the nation’s most rancorous debate. “I think it’s up to your perspective, right?” he asked.

“What we tried to do is really just lay out the facts of how Roe v. Wade came to be and how it was decided,” he said. “People can take one view or another. I’ve had a lot of people who think it’s in the middle.”

Loeb also pointed to his portrayal of Dr. Bernard Nathanson, a prolific practitioner of abortion who helped shape the movement for its legalization in the United States. Nathanson later became devotedly pro-life and was involved in tell-all projects like the 1984 movie The Silent Scream — from which Loeb and Allyn’s work draws much of its information.

In Roe v. Wade, Nathanson says, reflecting on the mortality caused by illegal abortions, that he chose his career so that “no woman ever had to (die) again.”

“There are characters who are generally trying to support abortion for serious issues,” Loeb observed. “Betty Friedan really wants to save women and help women. This is really an important thing, and we don’t vilify her at all.”

The first-time director echoed those sentiments in his remarks for the crowd at the debut. “Why are all these actors, producers, people part of it when it’s such difficult subject matter?” Loeb asked in his short opening speech on the main stage. “They wanted to be involved in telling the truth, telling both sides of what actually happened in 1973.

“The goal is not to get you guys to support it,” he said, “but the others who may not agree with us — to win their hearts and minds.”

Amid the palm trees, all the invective and investigative reporting was almost — but not totally — forgotten. “The media’s gonna write what they’re gonna write anyway,” Loeb said.

Perhaps characteristically, Lahren adopted a more combative tone when she received the microphone from Berning, the opening speaker. “People tried to shut us down. People are not being taught this story in schools, the true story of Roe v. Wade,” she said. “No matter which side you fall on, it’s an important film to see.

“They say I’m an actress, but I was only in this movie for about three minutes,” Lahren joked about her brief appearance. She plays Justice Harry Blackmun’s daughter Sally, who volunteers at Planned Parenthood and tries to influence his vote.

Indeed, many conservative actors joined the cast, reportedly for lower than usual salaries. Jon Voight portrays Chief Justice Warren Burger while Stacey Dash is Dr. Mildred Jefferson, a co-founder of the National Right to Life Committee who later served as its president.

Criticism of the film’s approach has been loud. It centers on claims that historical interpretation is presented as fact and that members of the production crew who quit upon reading the full script felt they had been misled.

Salon depicted assistant director Ben Collinsworth as one example among many. After a normal hiring process, he came, by his own account, to the rapid realization that details of the screenplay had been withheld. “I felt this script was a false account of history,” he is quoted as saying, “and the writer was engaging in disingenuous character assassination.”

Critics have also attacked Roe v. Wade for misquoting Abraham Lincoln and Benjamin Franklin. Additionally, the movie’s depiction of birth-control activist Margaret Sanger has been targeted.

Sanger is shown speaking to Ku Klux Klan members while a cross burns. The fact that she delivered such a speech is not disputed — but its content is. It includes racist language about eradicating Black people via abortion that Sanger biographer Jean H. Baker rejects as an inaccurate representation of Sanger’s opinions.

Loeb and Allyn counter that 40 percent of abortions are performed on African Americans, and they take pains to name their sources. In fact, the picture’s last minutes are devoted to citing the books, down to page numbers, that they scoured in order to include such material as a jingle Nathanson is heard to sing: “There’s a fortune in abortion.”

They show footage from ABC’s Nightline of Norma McCorvey — the real Jane Roe — calling her lawyers in the case liars. And they cite Sanger’s autobiography for the Klan scene.

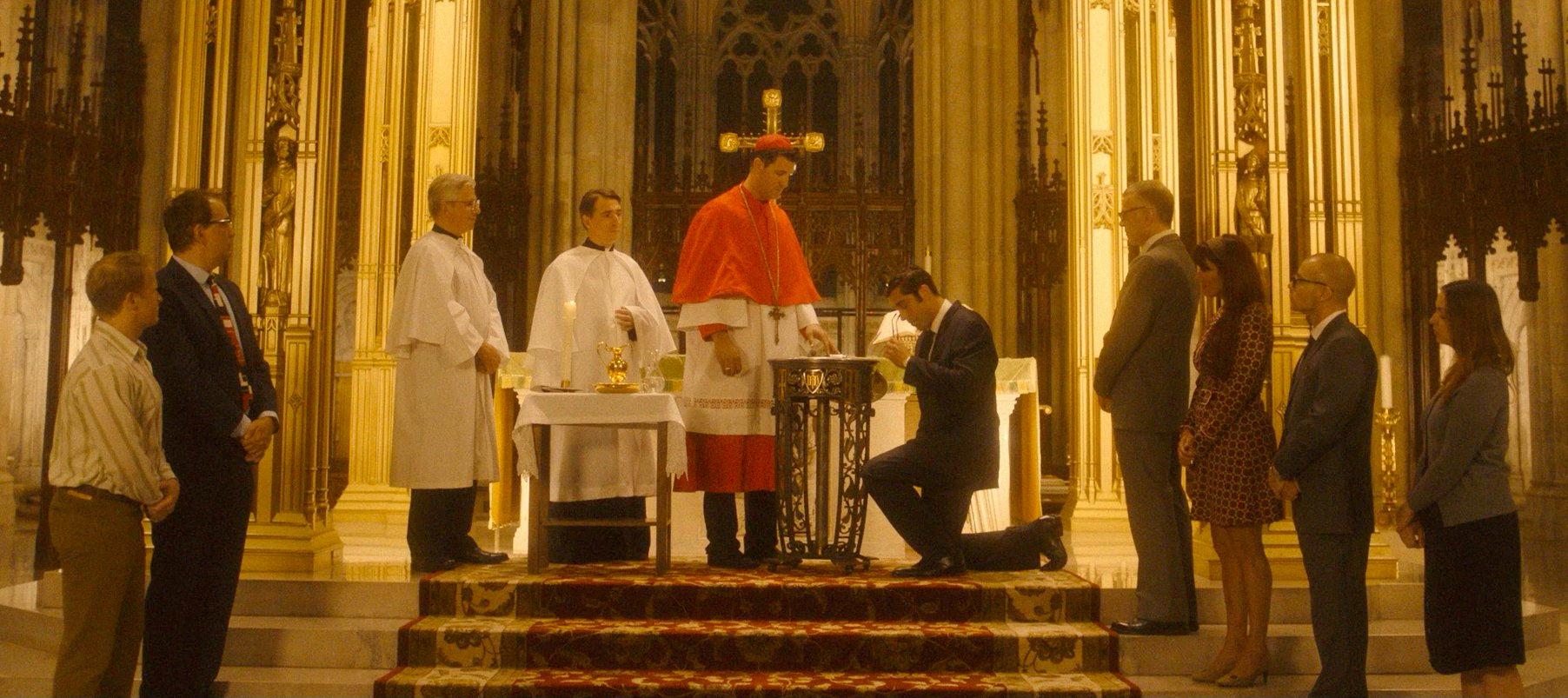

New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the National Mall in Washington are easily recognizable in the movie. But several host venues including Tulane University — Loeb’s alma mater — and Louisiana State shut down production. Loeb maintains it was because of the film’s subject matter; the schools cite logistics.

Other questions surrounding the movie concern its graphic depiction of abortion. Is this content propaganda intended to shock or an honest portrayal of the procedure? Roe v. Wade includes a few scenes of patients in distress as well as three quick shots of aborted fetuses — one of these is purposefully kept out of focus, but another is clear and distinct.

Loeb is likely to have culled from his own experience in preparing to portray Nathanson. The actor has openly regretted the two abortions carried out on previous partners of his — the same number the film depicts women involved with Nathanson as undergoing. Loeb credits the sadness he felt in the wake of these events with reversing his views on the subject.

Loeb’s legal battle with his ex-fiancee, actress Sofia Vergara, over the fate of embryos the pair had frozen has, moreover, been a well-publicized one.

The credits list the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s niece, Alveda, a former member of the Georgia House of Representatives, as an executive producer. And various Catholic organizations are named as well.

As for the picture’s unusually long crawl of special thanks, it includes expressions of gratitude to many small, independent financial backers like the young Seagraves family of Tennessee. They made an eight-hour drive to be present at the premiere, where they were seated in a “silver guest” section just a row or two behind some of the cast.

Roe v. Wade was screened at the Vienna Independent Film Festival last year, winning its Best Supporting Actor award for Voight. It’s scheduled to open in wide release April 2.

Augsberger is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.