PINE RIDGE, South Dakota — Middle schooler Rarity Cournoyer stood at the heart of the Red Cloud Indian School campus and chanted a prayer song firmly and solemnly in the Lakota language — in a place where past generations of students were punished for speaking their mother tongue.

Her classmates stood around her at a prayer circle designed with archetypes of Native American spirituality, with a circular sidewalk representing a traditional medicine wheel.

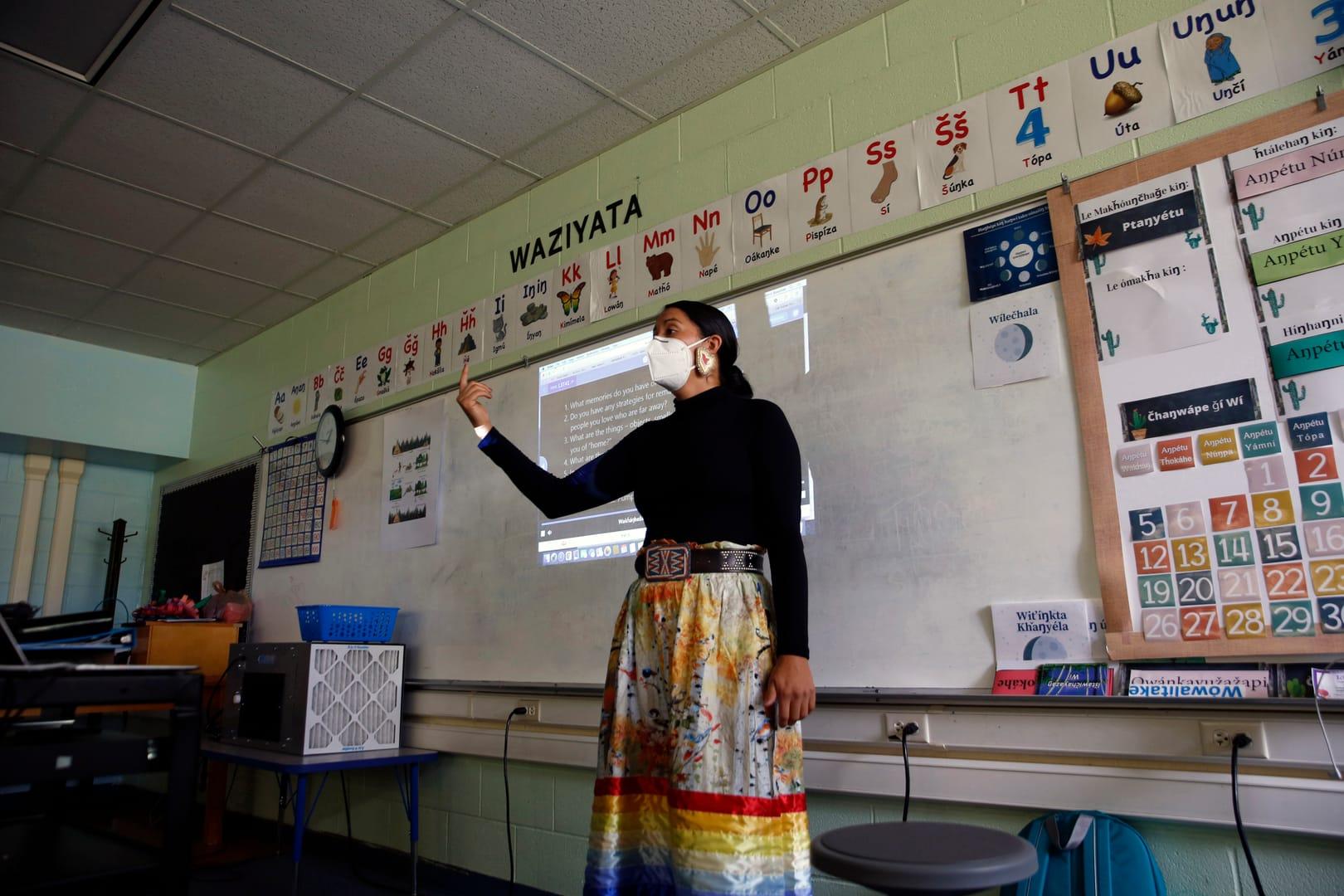

Lakota language teacher Amery Brave Heart walked quietly with a small bundle of smoldering sage stems. Brave Heart — sporting a long braid on the very campus where his grandfather, Basil Brave Heart, said he had his long hair shorn and carelessly trampled on as a newly arrived pupil — offered the sage to each student as part of a brief smudging or purification ritual, in which they symbolically waved the scented smoke toward themselves.

Such scenes would have been hard to imagine here decades ago when Holy Rosary Mission — as the Catholic K-12 school was then named — formed part of a network of boarding schools across North America where generations of Indigenous children were brought to weaken their bonds to tribe and family and assimilate them into the dominant white, English-speaking, Christian culture.

But while Lakota staff, language and ritual have increasingly become central to Red Cloud, the 133-year-old school has never fully reckoned with this history, which has alienated many Lakota living on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, one of the nation’s largest.

Now the school is undertaking what it calls a Truth and Healing process, seeking to hear the stories of former students, open its archives and face its past.

The ceremony at the prayer circle was a way of acknowledging that history, one of several small gatherings held at Red Cloud on the last day of September to mark what’s come to be known across North America as Orange Shirt Day.

Many students and teachers wore orange in solidarity with Indigenous children of past generations who suffered cultural loss, family rupture and sometimes abuse and neglect while compelled to attend residential schools from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries.

The event commemorates the long-ago account of an Indigenous woman in Canada whose residential school confiscated her orange shirt — a cherished gift from her grandmother — and made her wear a uniform.

“Our ancestors faced a lot in their time, but they remained resilient,” Red Cloud senior Mia Murdoch told fellow students during the high school’s observance. “They weren’t allowed to express themselves or to rejoice in who they were. We as young people now have those privileges. … Orange Shirt Day is not just a single day. It is a confrontation of the past and a conversation that takes place over a long period.”

The school’s Truth and Healing process, begun in 2020, is following four steps described as confrontation, understanding, healing and transformation.

“We’re really in the early stages of confrontation,” said Maka Black Elk, executive director for Truth and Healing at Red Cloud.

“I think people want to rush quickly to healing because it’s hopeful … but there’s a lot more that needs to happen before we can,” he said.

That includes giving former students a chance to tell their stories, whether in public settings or confidentially.

It will also involve a deep dive into school archives, even if it yields stories “we don’t want to hear,” Black Elk said.

The Truth and Healing process comes amid larger-scale reckonings by governments and church groups that ran residential schools.

Earlier this year in Canada, specialists using ground-penetrating radar discovered hundreds of unmarked graves at former school sites. A 2015 report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada said residential schools were often abusive, unsanitary and unsafe.

While school conditions varied across the U.S. and Canada, and some former students say they had positive experiences, even schools with better track records were serving in the larger project of cultural assimilation — what some call cultural genocide.

At least 367 such boarding schools once operated across the United States, about 40 percent of them affiliated with Catholic or Protestant churches, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. Most have closed, and most of the remaining ones, including Red Cloud, no longer board students overnight.

Holy Rosary, long staffed by Jesuit brothers and Franciscan nuns, boarded students for nearly a century after its founding in 1888.

A small group of Jesuits remain, but much else has changed at what is now a day school, with a total enrollment of 600 at its main campus and a second elementary school about 30 miles away.

Still, the wounds remain for many.

“This is something that people in the community who are from here have known about for a long time,” Black Elk said. “It’s their family history.”

Black Elk said the school plans to use ground-penetrating radar next summer where unmarked graves are suspected — in tandem with archival research about student deaths.

“It isn’t to do a quick and dirty measure of what your number (of graves) is. That’s actually traumatizing,” he said. “Really what ground-penetrating radar is about is healing. You’re finding people. You’re trying to find names, and a story about why that person is there.”

The Jesuits at the school, as elsewhere, are undergoing their own soul-searching.

U.S. and Canadian Jesuit leaders issued a statement of regret in August for the suppression of Native culture. They pledged to help “shine the light of truth” on this history.

“The pain or the trauma of that past can hold us back no matter what positive moves we’ve made,” said the Rev. Peter Klink, former president and now vice president for mission and identity at Red Cloud. “We’ve got to pursue the truth so that we understand fully the past.”

AP journalist Emily Leshner contributed to this report.