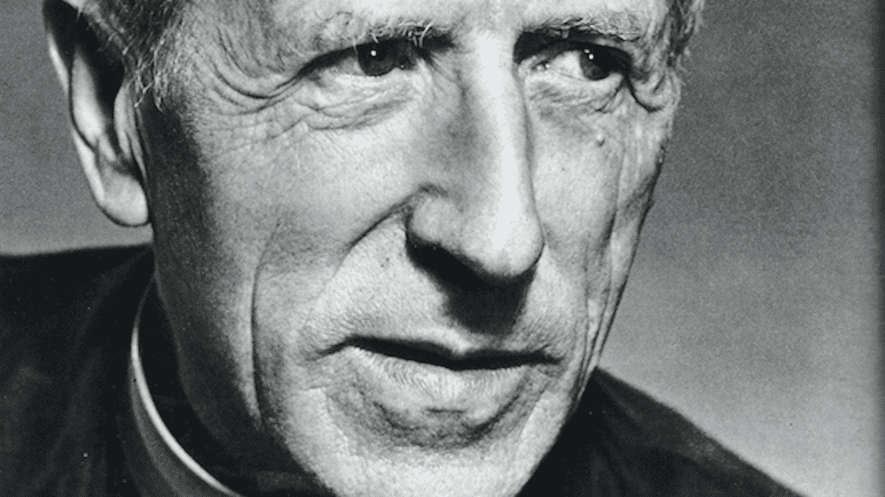

LEICESTER, United Kingdom – For nearly a century, a controversial Jesuit scientist’s statement of faith had been stored away in the Jesuit archives in Rome, forgotten if not exactly lost. And perhaps fittingly for a man whose work touched on the mystical and looked at mankind’s place in the cosmic drama, it was found not by a scholar, but by an actor researching a play.

French-born Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (May 1, 1881-April 10, 1955) had a monitum – an official warning – attached to his work by the Holy Office, the forerunner to today’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in 1962. That monitum was reaffirmed by the Vatican in 1981, on the 100th anniversary of Teilhard’s birth.

Despite this official warning, his main books – The Phenomenon of Man and The Divine Milieu – remain popular today, and his work was citied positively by Pope Benedict XVI and was mentioned in Pope Francis’s ecological encyclical Laudato Si’.

(Last year, the Vatican’s Council for Culture asked that the monitum on Teilhard’s work be lifted.)

RELATED: Rehabilitation won’t do much for Teilhard, but symbolically it matters

Teilhard was a scientist who worked primarily in paleontology, and his theology heavily relied on evolutionary theory, and posited all creation is moving towards an “Omega Point” of divine unification.

In 1925, the Jesuit was asked to sign a document assenting to six propositions, including traditional teachings on original sin and the place of Adam and Eve in Church teaching.

The document sat in the Jesuit Archives in Rome until found by actor and writer Paul Bentley, who was researching a play on the Jesuit.

Bentley, best known for playing the High Septon on HBO’s Game of Thrones, spoke about the document on Feb. 22 at a day-long event on the propositions taking place at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“They are essentially six of the traditional teachings of the Church about Adam and Eve and Original Sin,” Bentley said, according to the Scottish Catholic Observer. “He had to sign up to all six and he was prepared to sign five of the six, but the fourth proposition he felt he couldn’t sign up to because, as a scientist, he didn’t believe it was true.”

Eventually, Teilhard did sign all six.

Bentley said he had been interested in the Jesuit theologian since attending a Jesuit grammar school and wanted to write a play on Teilhard’s struggle to sign the propositions.

When the Vatican archives from 1922 to 1939 were opened, he saw his chance to seek them out, but they weren’t there.

Eventually, he found his way to the Jesuit archives, and found the document after searching several files from the time period.

Bentley doesn’t think they had been deliberately hidden away, but that “no one has been as curious as me,” and he needed to see the propositions to properly write his play.

A staged reading of the work, titled Inquisition, was part of the conference.