LEICESTER, United Kingdom – Thou shalt not kill: Although you might recognize this from the ten commandments, it is also the first, and one of the few, rules of the Royal Shrovetide Football Match.

While many people might be celebrating Shrove Tuesday by having one last night out on the town before Lent – or follow the English tradition of having pancakes – thousands will descend on the town of Ashbourne to watch, or participate in, one of the most unique sporting events in the world.

The two teams are made up of people who were born on the different sides of the Henmore River which divides the town called “up’ards” and “down’ards.”

There are two goals over two miles apart, and the ball can be carried, kicked, or thrown, but this rarely happens. The ball is moved through “hugs” – think Rugby scrums – punctuated by swift runs when the ball breaks free, and will be moved through the town, over the river, and through the woods in an attempt to score; according to the locals, the ball is “goaled.”

It is a physical affair, but outright violent action is officially frowned upon.

“For someone who was observing the game for the first time my first – and last – instruction would be: Keep your distance!” said Father John Guest, pastor of All Saints Catholic Church, the local parish.

“Play looks like mayhem, but the thirty to fifty regulars who constitute the heart of the teams have their well-hatched plans and do try to follow them,” he told Crux.

The origins of the game are lost in the mists of time, but it probably descends from the many local ballgames which were common in the Middle Ages around Shrove Tuesday, Easter, and Christmas.

The first historical mention of the game in Ashbourne was in the 1600s, and like many such games in England, the play was somewhat standardized in the 1800s.

For instance, no playing in cemeteries, churchyards and the town memorial gardens; no playing after 10 p.m. (when the town warden calls time); and to “goal” the ball, you have to tap the ball three times in the goal area.

Some of the rules came about because of the changes of the 20th century: No hiding the ball in your backpack or carrying it in your car or on a motorcycle. Also, don’t even think about throwing a fake ball into the fray.

And even the name is a modern invention: The match didn’t become “Royal” until 1928, when the Prince of Wales turned up.

Although these slight modifications may have brought about a greater sense of fair play, it didn’t really civilize the game.

“It is a bit like free-for-all rugby or American football without any protective clothing. It usually spends a good deal of the afternoon in the River Henmore,” Guest said.

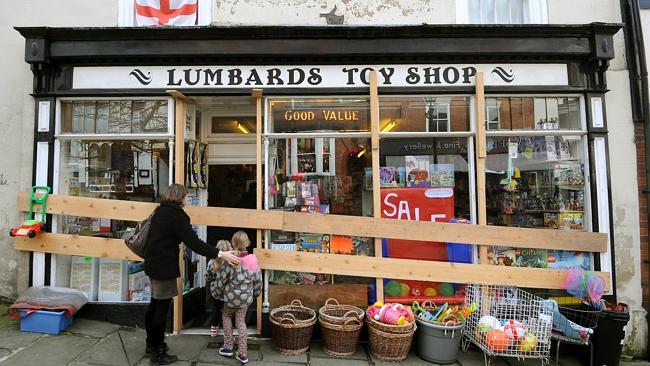

“There are the usual injuries and breakages. Town center shops usually close and have wooden bars hammered across their windows,” the priest said, although he noted “fighting is frowned upon.”

“The pubs of course remain open throughout. For many in the town it is the defining moment of the year. Others prefer to be elsewhere!”

Despite the chaos, the game is a central part of the life of the town. Not only does it bring in tourists – and their money – it is also a time when people born in the town return home and have a chance to see family and friends.

It is also a chance for the town – population 7,000 – to host celebrities and dignitaries, who have the honor of throwing out the ball, called the “turn up,” to start the match.

“It is a great honor to ‘turn up’ the ball, and the persons chosen tend to be celebrities or people who have contributed greatly either to the game or to the town of Ashbourne,” Guest said.

“The balls are beautifully decorated with details of the life and actions of the one doing the ‘turning up,’ though most of the art will have disappeared by the time the ball has been ‘goaled,’ if indeed that happens. If it is not goaled it, is kept by the turner up, if it is goaled it is kept by the one who scores the goal,” the priest told Crux.

The ball is “turned up” at 2 p.m. on both Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday. If it is “goaled” before 6 p.m., another ball may be “turned up” or introduced into play. If a goal occurs after this time, it signifies the end of play. If there has been no score by 10:00 p.m., the stewards will bring play to an end.

Goals are very rare, and a 0-0 tie is not uncommon. In 2011, the score was 2-2, considered a fairly high goal total.

Scoring a goal is considered a great honor, and within the “hug” the person who will “goal” the ball is determined: This keeps tourists from scoring one of the rare goals.

Guest says he is lucky: “The Catholic Church is on higher ground away from the river and the center of town and so is far away from any route the rampage is likely to take.”

He said his parish has no official involvement in the game, although parishioners have taken leading roles in the organization and administration of the match.

“Many of [All Saints] parishioners have claimed fame as supreme exponents and famous ‘goalers’ in the past,” Guest said.

“As far as I know, the Church has never complained about the game taking place on Ash Wednesday, though it can be difficult for parishioners to get to the blessing of the ashes and evening Mass if the route of the game happens to cross their route to church, but this rarely happens, and the locals have grown used to finding an alternative means of access,” he added.