LONDON — In a gallery of The British Museum, light plays on an array of medieval crosses, reliquaries and manuscripts, as an audiovisual display reenacts one of English history’s most notorious crimes.

At the center, three stained-glass windows, painstakingly transferred from Canterbury Cathedral, convey images from the fabled afterlife of St. Thomas Becket (1120-1170), next to badges and keepsakes left by generations of pilgrims at his place of martyrdom.

When the exhibition, “Murder and the Making of a Saint,” opened in May, as England’s coronavirus lockdown was relaxed, the curators said they hoped to depict Becket’s journey from a humble clerk to one of Europe’s most popular miracle-working saints.

Three months on, after attracting record crowds for the 850th anniversary of his death, many are struck by the exhibition’s warm evocation of the country’s Catholic past and dramatic reconstruction of the centrality of church and faith.

“There’s no doubt the anti-Catholicism long embedded here is dissipating now, enabling a more sympathetic understanding of the past, which cultural events like this can subtly reflect,” Jesuit Father Timothy Byron, a historian, told Catholic News Service.

“There are issues surrounding our religious and cultural identity and how we evaluate our history and a better climate now for debating the place of our Catholic and Protestant traditions.”

Born in London, Becket studied in France and Italy, rising to become a senior lay office-holder at Canterbury for Archbishop Theobald of Bec.

In 1155, he was appointed chancellor to King Henry II, responsible for royal revenues, becoming a close and trusted confidant; just seven years later, after Archbishop Theobald’s death, the king named him archbishop of Canterbury.

The top church post carried vast wealth and power. But Becket, a fine horseman and sword-fighter, was not even a priest. So the surprise appointment also required, in the words of the curators, “some stage management.”

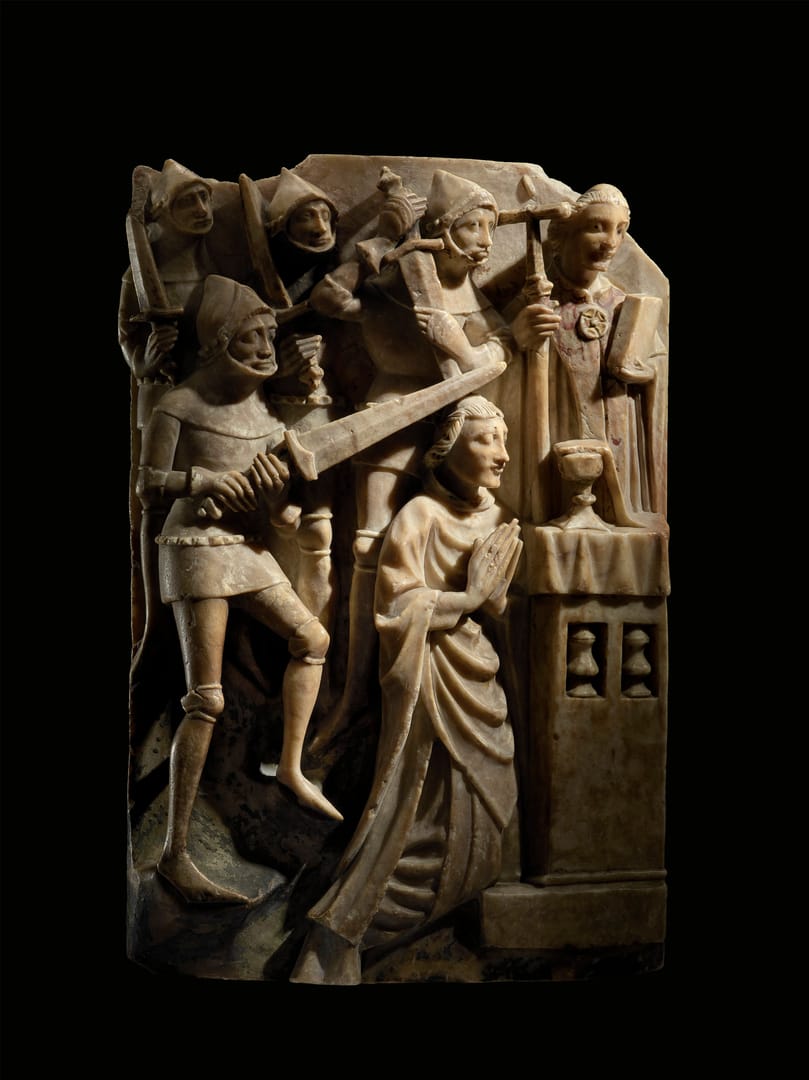

The exhibition includes artifacts from Becket’s early London life, a rare document bearing his seal, and an alabaster altar panel depicting him delivering a blessing at his episcopal consecration just a day after he had been ordained.

The exhibit also noted the king’s neat arrangement soon unraveled.

Henry had expected his new chancellor-archbishop to do his bidding, but Becket adopted an ascetic lifestyle and opposed the king’s authority, notably when he sought to tighten control over the church with a series of statutes in 1164.

With tensions rising, Becket fled abroad to the protection of the king of France, as the pope negotiated on his behalf.

He finally returned in late 1170 and was killed at Canterbury Dec. 29 by four knights who had witnessed the king’s Christmas tirade against “miserable drones and traitors” he had “nourished and promoted” in his royal household.

Evidence indicates the intruders planned to take Becket to Winchester. When he resisted, they lost control and hacked the archbishop to death in his cathedral during vespers.

Becket’s violent end, captured by five eyewitness accounts, shocked Europe — sending, in the curators’ words, “strong echoes out down the centuries.”

His martyr cult quickly developed, and just 26 months later, he was canonized by Pope Alexander III, making Canterbury Europe’s foremost pilgrim center after Rome, Jerusalem and Santiago de Compostela.

His four disgraced murderers later died while serving in the Holy Land by papal order, while in 1174, Henry II begged forgiveness.

Becket’s fame is recalled in objects such as a gilded blue-green casket, which would have contained fragments of his bones or bloodied clothing, as well as in the stained-glass cathedral “Miracle Windows,” depicting cures at his intercession.

An original copy of Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales,” the first book printed in English, shows how Becket’s story quickly became rooted in public imagination.

Father Byron, the historian, thinks Becket’s enduring cult typifies how popular devotions can endure for centuries, against all efforts to diminish them, if the “soft power” they represent is effectively harnessed and directed.

Joseph Shaw, an Oxford lecturer on medieval philosophy, agrees and is struck by the exhibition’s sympathetic portrayal of Becket.

“Catholics have often been presented here as peddlers of strange superstitions — but this exhibition shows a detachment from sectarianism and a real willingness to engage with what Becket achieved,” Shaw told CNS. “Though it shows there are two sides to the story, it also reflects today’s greater openness, which is enabling people to look at art, theology and history more objectively.”

During the 16th-century Reformation, King Henry VIII declared Becket “no longer a saint, but a traitor to the crown.” All references to Becket were ordered erased from prayer books, while the king proclaimed an end to his feast-day — a move that shocked Europe and hastened Henry’s excommunication.

People drew parallels between Becket and the new generation of Reformation-era martyrs, notably St. Thomas More, who also was a royal chancellor. The Catholic English College in Rome, training priests for secret ministry, promoted Becket “as a model for emulation.”

The exhibition includes a carved marble base from Becket’s desecrated tomb, found in a river near Canterbury, as well as a bone fragment reputedly from the saint’s skull, which was smuggled abroad to an exiled Jesuit college in France.

Shaw thinks the exhibition’s connection of Becket with later Catholic persecutions is significant.

“It’s a reminder that, even after the terrible destruction of the Reformation, Catholicism still remained the true faith of many English people,” Shaw told CNS.

Ruth Cornett, an art historian from Northern Ireland, admits it’s difficult for any exhibition to capture complex historical ideas through material objects or to retrace political and ecclesiastical divisions for modern minds. But the exhibit shows what was lost to spiritual life from Reformation disputes, she said, and will resonate with people familiar with the modern killing of outspoken clergy, as well as with images of cultural and artistic vandalism from Afghanistan to Syria.

“Becket’s instant fame across Europe, where Christians were horrified by his fate, shows how the church of the day knew no borders,” Cornett told CNS.

“Today, when education is key, exhibitions like this can help widen knowledge and understanding, by challenging perceived truths about the past.”