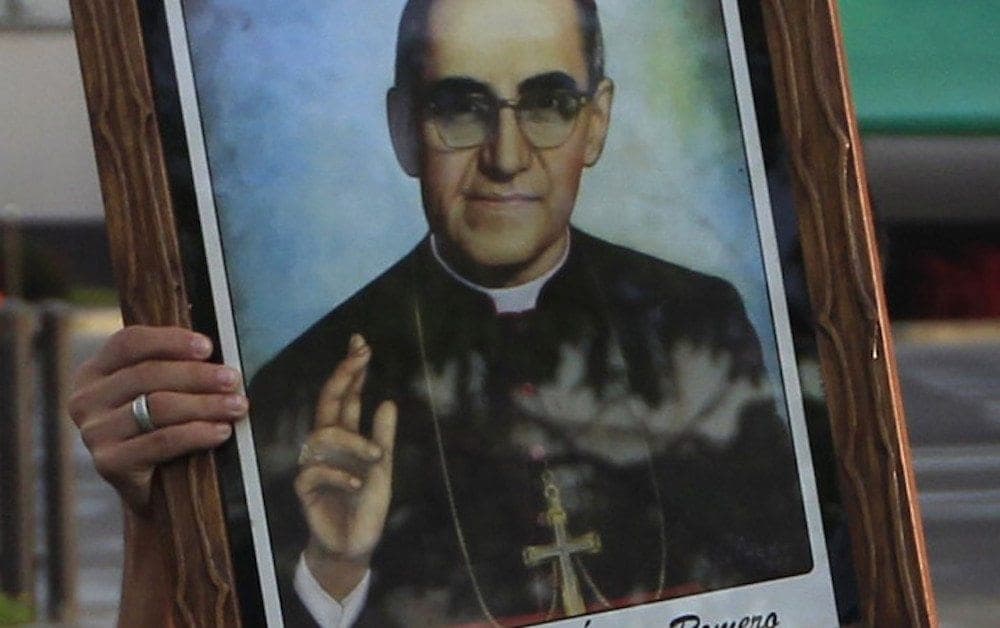

SAN SALVADOR — When the Catholic Church declares someone “blessed,” the final step before sainthood, it’s a person receiving the honor, not a symbol. In the case of the late Archbishop Oscar Romero, however, the symbolism sometimes has obscured important aspects of his life and of his legacy.

At the symbolic level, Romero has often been seen as a sort of Che Guevara in a cassock, a progressive firebrand who challenged an oppressive U.S.-backed regime in El Salvador and paid the ultimate price, shot to death while saying Mass on March 24, 1980.

In truth, Romero was a more complicated figure. The following are five surprising aspects of his life and legacy, which together represent the Oscar Romero you probably don’t know.

1. Romero wasn’t a liberation theologian

The Salvadoran prelate is conventionally seen as a champion of liberation theology, a progressive movement in Latin American Catholicism that seeks the place the church on the side of the poor in struggles for social change.

Liberation Theology was partially condemned by the Vatican in the 1980s for its tendency to mix Marxist social analysis and concepts such as “class struggle” with religious commitments.

Peruvian Theologian Rev. Gustavo Gutiérrez, widely considered the founding father of Liberation Theology, has repeatedly said that Romero didn’t belong to the movement.

Speaking to Crux in San Salvador, he said Romero didn’t adhere to any particular theological path, to one school or the other.

Romero was not “cloistered or encapsulated in only one current,” Gutierrez said.

There would have been no reason for him to be so, he said, because “theology is more flexible than that, and because there are coincidences in different theologies as basic messages.”

If anything, Gutiérrez said, Romero was a traditional person, “but in the good sense: Not exactly conservative, but a very pious person.”

That isn’t to say he was against Liberation Theology.

In 1972 Romero participated in a one-month conference for bishops of Central America. Gutiérrez was in charge of one week of the program and still has the notes Romero took. In them, Romero expresses his interest on the subject.

The Rev. Jesus Delgado, Romero’s personal secretary, claims that his late boss was never swayed by the many Liberation Theology proponents who visited him and gave him books on the subject.

“I saw [the books], and they were brand new, Romero never even opened them” Delgado said last February in Rome. “On the other hand, all the books of the fathers of the Church were worn and were the source of his inspiration,” he said.

2. Romero was friendly to Opus Dei

For Delgado, there’s more truth in the claims that Romero was close to the Opus Dei, a somewhat conservative lay organization (technically, it’s a “personal prelature” in church law.)

For almost 15 years Romero had a spiritual director/confessor from the Opus Dei – first the Rev. Juan Aznar and later the Rev. Fernando Saenz, who would replace Romero as Archbishop of San Salvador after his death.

Romero went to the beach with a group of Opus Dei friends on the morning of the day he was killed. He also met with St. Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei, several times in Spain and in Rome, and exchanged letters with him.

Speaking to Crux in Rome, Delgado expressed his disappointment with the way Opus Dei ignored the link between Romero and the group during the 35 years it took for the Vatican to recognize his martyrdom.

Salvadorian Carlos Mayora Re, local spokesman for the Opus Dei, said he’s spent considerable time reflecting on this silence. Speaking in a personal capacity, he said he found three reasons for it.

The first, he said, is the fact that the church in El Salvador was used to preaching and dictating positions, not to listening and dialogue, so when it came to making a stand in favor or against Romero, they waited for the Vatican to decide.

The second reason, according to Mayora Re, was a fear of being perceived as Marxists during the 12-year long civil war (1980-1992).

The last reason, Mayora Re said, was Colombian Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo, whom he defined as a “highly prudent person”, and who made clear his opposition to Romero’s beatification.

Lopez Trujillo died in 2008, around the same time Pope Benedict XVI lifted an informal block on Romero’s sainthood cause.

3. Romero did not back El Salvador’s guerillas

There were reasons many Salvadorans saw Romero as someone too close to the guerrillas, such as his habot of celebrating funeral Masses for priests killed for embracing armed struggle.

However, according to Mayora Re, “it’s clear that Romero wasn’t a Communist.”

“He was a bishop who knew himself to be a father to his priests and who saw the church as their mother,” Mayora Re said.

“Others claim to have seen him with family members of the guerrillas,” he said. “It’s true, he was with them, but because he didn’t believe in second-hand information, he wanted to see the bodies of those murdered by the military … He didn’t deny comfort to anyone who needed it.”

4. Romero has his own United Nations Day

Another little known fact about Romero is that the United Nations considers March 24 to be the “International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims.” The date was chosen to honor the Salvadorian.

Roberto Cuellar, a lawyer who was hired by Romero to run a free-legal assistance office in San Salvador and who currently works as representative of the Organization of American States in El Salvador, describes the archbishop as a precursor in the fight for human rights in the country, and the first one to openly criticize the corruption of the local legal system.

Cuellar told Crux that during the three years they worked together, Romero wanted weekly updates on the cases they were working on, in order to personally decide which ones he could denounce from the pulpit.

“He wanted for us to thoroughly research each claim, to pay attention to the people behind them, to listen to the roots of the problems, to verify the facts, and help the victims,” Cuellar said. “He wanted justice to be available for all, not only those who could afford it.”

Romero is the only Central American with a U.N. day dedicated to his memory.

5. Romero will be the first Salvadoran saint

As of Saturday, Romero is the first officially recognized martyr of El Salvador, a country that in many ways is still suffering the violence the archbishop died trying to stop. In 2014 it hard the world’s highest murder rate, with an average of 12 to 21 people killed each day, mostly victims of the country’s notorious criminal gangs.

Although beatification is merely the penultimate step before sainthood, there’s every indication Pope Francis intends to move Romero across the finish line quickly.

Back in 2007, then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina reportedly told a Salvadoran priest that “to me [Romero] is a saint and a martyr … If I were pope, I would have already canonized him.”