MEXICO CITY — Pope Francis began his Feb. 12-17 visit to Mexico on Friday, becoming only the third pope to visit the country. In truth, however, the land of mariachis and tequila is a favorite papal destination, since John Paul II came to Mexico five times and Benedict XVI once, in 2012.

Much has changed since that first papal visit in 1979, but some things are still the same.

St. John Paul II never attempted to hide his predilection for the United States’ southern neighbor. Outside of his trips to his home country of Poland, along with France and the U.S., John Paul II visited Mexico more than any other country in the world.

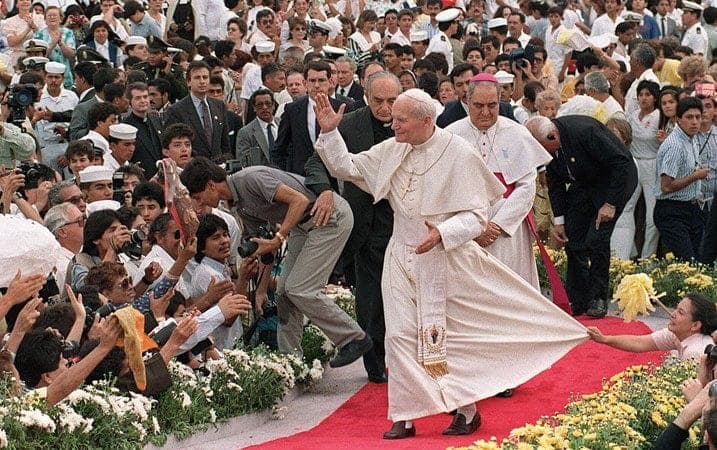

The “pilgrim pope” visited Mexico in 1979, 1990, 1993, 1999, and in 2002.

Mexico was the first foreign trip of his papacy, and it came only four months after his election, accepting an invitation to his predecessor, John Paul I, to attend a meeting of the Latin American bishops in Puebla.

The trip established John Paul II’s reputation as a magnet for humanity, with an estimated 10 million people coming out to see him during the six-day visit.

That foray hinted at the ambivalent relationship John Paul would have with liberation theology, as he denounced social injustice, but also underlined the “primacy of the spiritual”, rejected Marxism, and insisted on unity in the church.

“When they begin to use political means,” he told the bishops about followers of the Latin American movement, “they cease to be theologians.”

His first visit to the land of the Guadalupana was also a challenge to Poland: How could his home country, still under the Soviet Union, deny him entry, if an anti-clerical Mexico had surrendered at his feet with millions of people coming out to see him?

Reports say that large crowds would gather close to where John Paul was sleeping, to sing him the song “Amigo” by Brazilian artist Roberto Carlos.

Several times the Polish pope came out smiling, to tell his Mexican hosts: “Papa quiere dormir, dejen dormir a papa” (“The pope wants to sleep, let the pope sleep!”)

“It is said of my native country: ‘Polonia semper fidelis,’” he said at the cathedral church, on the first day of that 1979 visit. “I want to be able to say also: Mexico ‘semper fidelis,’ always faithful!”

The visit wasn’t free of political turmoil. At the time, the Vatican and Mexico had no diplomatic relations, so the pope hadn’t been formally “invited” by the government.

Throughout the trip, John Paul II broke the law by wearing a cassock in public (the bishops who greeted him at the airport were in coats and ties), and was welcomed by then-President José López Portillo as an “illustrious visitor.”

The second visit of the “pilgrim pope” took him on a tour that would put most mortals — and perhaps even Francis, who visited three countries in six days in Africa last November — to shame: During the 47th pilgrimage of his papacy, John Paul visited 10 Mexican cities in eight days, with a stop for prayers and jet fuel at the Caribbean island of Curacao on the way home.

Although his addresses and homilies were plentiful, for locals and observers alike, this is remembered as the visit in which he beatified Juan Diego, a native Mexican peasant to whom Our Lady of Guadalupe first appeared in 1531.

In Catholic parlance, “beatification” is the step previous to sainthood, an honor bestowed upon Juan Diego during John Paul’s last trip to Mexico, in 2002.

His 1993 visit was shorter, basically a stop-over on his way to Denver, and it was centered in Yucatan. It was preceded by the murder of Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo of Guadalajara, who was shot 14 times in his car in the parking lot of the local airport.

(A government inquiry concluded he was caught in a shootout between rival cocaine cartels and was mistakenly identified as drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, head of the Sinaloa Cartel.)

Despite newly re-established diplomatic ties, the pope still wasn’t received as a head of state. However, President Carlos Salinas de Gortari addressed him as “Your Holiness.”

He had only two official engagements: an address to the local indigenous communities, and a Mass on the following day, also for that crowd.

During this visit, his focus was on depicting the Church as a defender and protector of indigenous Americans and on promoting a new economic order in the wake of the Cold War.

In a speech that could very well be read by Pope Francis today, the Polish pope called for developed societies “to overcome economic systems oriented solely toward profit and seek real and effective solutions to the serious problems that afflict wide sectors of the continent’s population.”

In 1999, he visited Mexico for four days and stayed in the capital city, where he met with patients at a hospital and held several open-air events.

From the Tepeyac hill, where Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared to Juan Diego, he proclaimed Dec. 12 to be a feast for the whole continent, and elevated the Guadalupana to the honor of “Patroness of the Americas.”

During his last visit in 2002, and with his movement visibly affected by an advanced stage of Parkinson’s disease, the pope gave the Church what he described as “the gift of the first indigenous saint of the American continent.”

John Paul II described Juan Diego as an important force in the spread of Catholicism among this region’s Indians, whose contributions the pope repeatedly praised.

“Christ’s message, through his mother, took up the central elements of the indigenous culture, purified them, and gave them the definitive sense of salvation,” the pope said.

Benedict XVI visited Mexico only once, on his first foray to Spanish-speaking America. Like Francis, who met the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church at the airport in Havana, he included a stop in Cuba, but on the way back.

This papal tour skipped Mexico City in favor of Guanajato, birthplace of Mexican independence and of an armed uprising against harsh anti-clerical laws in the 1920s.

There were two reasons for the choice: one, the health of Benedict, who hadn’t received the all-clear from his physicians to go to Mexico City due to its high elevation, and because his predecessor had never visited the area during his five trips to the country.

During his visit, he paid special attention to children, meeting thousands of them at the Peace Plaza, and played to the crowd by wearing a classical “charro” hat.

Benedict’s trip came just before presidential elections, so just like with Francis, the local Catholic hierarchy warned against seeing the visit in political terms. Mexican Cardinal Javier Lozano Barragán, a retired Vatican official who accompanied Benedict, said that trying to view the trip in terms of electoral politics “would be like forcing the ocean into an oyster.”

Expectations for the trip were low, yet an estimated 3.5 million people came out to see the German pope. Videos show thousands of faithful chanting “Benedict, brother, you are now Mexican!” He, too, woke up to serenades of two youths who sang him a traditional folk song, “Las Mananitas” (“The Little Mornings”).

No matter how rapturous the reception for history’s first Latin American pope turns out to be this week, therefore, it almost certainly won’t be anything Mexicans haven’t seen before.