Is it time to head for the hills? That’s what St Benedict did. By the end of the fifth century the great Roman Empire had completely collapsed. The center of government had moved to Constantinople. The Vandals and Goths had sacked Rome, and the church and people had drifted into decadence and despair.

As a young man Benedict went to study in Rome, but soon gave up and retreated to Subiaco to live as a hermit.

Conservative writer Rod Dreher thinks it is time for American Christians to consider what he calls the “Benedict Option”. He contends that Christians have lost the culture wars, predicts that persecution of Christians is right around the corner, and recommends heading for the hills.

Dreher has a wetted finger in the air, and he doesn’t like the way the wind is blowing. While the Little Sisters of the Poor and other religious organizations are awaiting a Supreme Court decision on religious liberty, Dreher cites last year’s battle in Indiana over the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

In the face of legislation promoting same sex marriage, Indiana Governor Mike Pence signed legislation that protected the religious freedoms of businesses and individuals. There was a widespread backlash—most importantly from business giants like Apple, GenCon and Subaru.

Dreher sees the Supreme Court decision last summer to allow same sex marriage as another major setback for historic Christianity, and he’s ready to throw in the towel.

In the face of increasing secularization, Islamic extremism, urban violence and economic uncertainty, many Christians are feeling nervous and threatened. Furthermore, they not only feel that they are on divergent paths with the culture, but they increasingly feel that discussion is pointless because discussion is impossible.

It’s impossible, according to this line of thinking, because the powers within academia, the media, big business and government have been caught up by what Pope Benedict XVI called “the dictatorship of relativism.” At its most fundamental, relativism rejects the idea of objective truth, thereby making any real debate impossible. If there is no truth, there is nothing but an exchange of opinions.

Abetting the decline of a Christian culture in America is the simultaneous decline of historic Christianity into what Christian Smith calls “Moralistic, Therapeutic Deism.”

Instead of Christianity being understood as a transaction with the supernatural through inspired Scriptures and effective sacraments, mainstream American Christianity (both Protestant and Catholic) has become a bland weekend activity for respectable suburbanites to encourage one another to be nice and overcome their problems. God is reduced to the Deistic version of a celestial Colonel Sanders who, if he exists at all, is having a nap.

American Christianity is therefore indistinguishable from American culture. Both accept mindless materialism as the default setting, and encourage a cheerful hedonism tempered by a self-help mentality in which nobody is really very bad, but neither is anyone really very good.

The result is a cultural collapse into mediocrity and mendacity: a whole population of the bland leading the bland.

Dreher defines the “Benedict Option” as “Christians in the contemporary West who cease to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of American empire, and who therefore are keen to construct local forms of community as loci of Christian resistance against what the empire represents.”

These communities keep alive classical education, nurture reverent worship and cultivate lasting and stable relationships with God and one another. The “Benedict Option” is therefore not so much a resignation in recognition of defeat as it is a retreat to a field of endeavor where something positive can be achieved.

Dreher’s dream has its critics, of course.

“Are we all supposed to become monks?” they ask. Others see the “Benedict Option” as a cowardly cop out or a romantic Utopian dream.

Others are more practical in their critique. “Isn’t the Benedict Option what the church should be doing anyway? Why the need to head for the hills?”

Dreher addresses frequently asked questions and gives examples of parishes, schools, religious communities and families who are consciously and quietly attempting a rejuvenation of Christianity and culture from within their own circumstances.

While one’s decision to take the “Benedict Option” may not be explicit and formal, Dreher’s idea can certainly be the spark for parish and personal renewal. We may not be able to head for the hills, but we can reassess the priorities of our communities and commit ourselves to local social action, renewal of classical education, reverent liturgy and deeper lives of prayer.

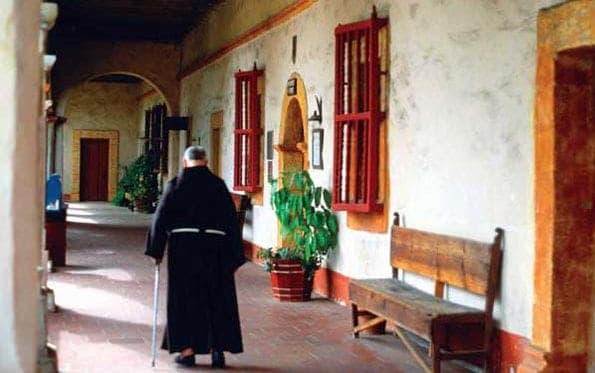

This is the step St Benedict took at the end of the fifth century. He established small communities of men and women whose lives were dedicated to worship, scholarship and work.

At Europe’s turning point from the classical age to the age of Christendom, Benedict did what he could, and the seeds he planted grew into a Christian civilization that lasted for a thousand years. Because of his simple faithfulness Benedict is acknowledged as the patron of Europe, and if they are faithful, his followers today might plant the seeds of a New Christendom.