It’s no secret that the off-the-cuff remarks of Pope Francis often generate more news than long, labored-over prepared texts. We tend to like our leaders, popes included, to come off as unfiltered, unhandled and unplugged.

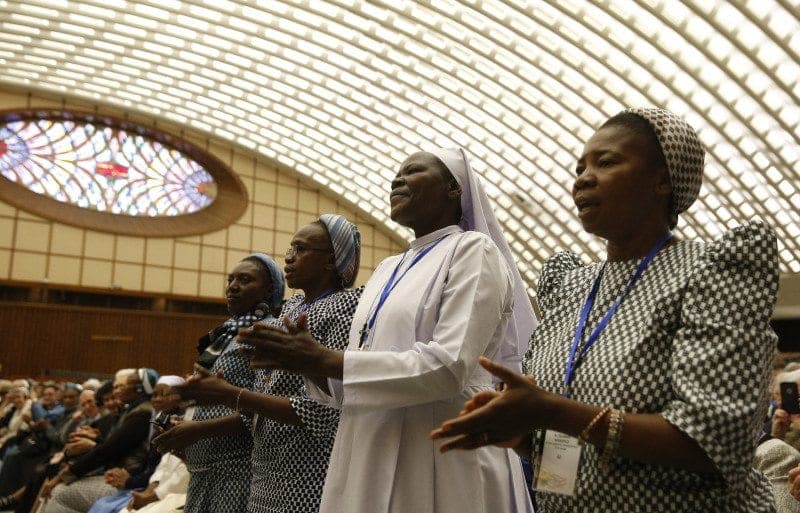

At a recent meeting of the Superiors General of Religious Women in Rome when asked about the possibility of women being ordained deacons, Francis responded, “I would like to constitute an official commission to study the question: I think it will be good for the church to clarify this point, I agree, and I will speak to do something of this type.”

With that simple statement, Francis opened a door that many had considered closed: the ordination of women. Francis himself has said that door was closed when referring to priestly ordination.

However, many have asked, if a woman can be ordained a deacon and thus gain entry to the clerical state, what is to prevent the same entrance to the priesthood? Has the time come to break through the “stained-glass ceiling” in the church?

In the wake of the hubbub created by the comments of Pope Francis, there have been the inevitable attempts to downplay their significance. Father Federico Lombardi, the chief Vatican spokesman said, “The pope did not say he intends to introduce the ordination of female deacons and even less did he talk about the ordination of women as priests.”

Technically, that’s correct, except that Pope Francis did introduce the possibility of a conversation about a topic that most assumed was off the table. (That’s despite the fact that women deacons were discussed as part of an International Theological Commission study of the diaconate 14 years ago.)

A woman religious and scholar said to me, “We were told it was an issue that we couldn’t even talk about. Now we are being told we can. It may not seem like a big deal to you, but it’s a big deal to me.”

It’s not only a big deal for women religious. People in the pews are also paying attention. At the parish where I assist on weekends, people were abuzz with consideration of what women deacons might mean for the Church.

One woman and parishioner said, “If women will be able to preach and do baptisms and marriages, it could be a first step toward someday being able to say Mass. I’ll really sing Alleluia on that day.”

That parishioner may have plenty of time to practice those notes, because her comments indicate a huge leap from where Pope Francis seems to be at the present.

The existence of deaconesses in the early Church, however, may be enough justification for Francis to revisit the issue and perhaps come to different conclusions than the International Theological Commission did in 2002. Some are hopeful this is the case; others shudder at the thought.

Welcome to our “wide-net” Church.

The exact role and function of women deaconesses is in need of discussion. There is little Scriptural and historical data to clarify a delineated ministerial role, though it appears that the ordination rite for women deacons in the early Church was virtually identical to that of male deacons.

In a culture where women were viewed and treated as inferior, the equal ordination rite alone merits attention and, as Pope Francis suggests, discussion. If a bishop once laid hands on a woman’s head and an “ontological change” occurred, who’s to say that can’t happen again?

The 3rd century document Didascalia of the Apostles exhorts the bishop to: “Appoint a woman for the ministry of women. For there are homes to which you cannot send a male deacon to their women, on account of the heathen, but you may send a deaconess… Also in many other matters the office of a woman deacon is required.”

It goes on to say that the bishop should see the male deacon as Christ and the woman deacon as the Holy Spirit.

This document indicates a valuable complementarity to the roles of deacons and deaconesses. It also seems to acknowledge that sometimes women can go where a man cannot. This could refer not only to the physical landscape, but perhaps to the emotional and psychological as well.

Pope Francis has been intent on talking about a “theology of women” and on exploring how leadership roles in the Church might be assumed by women. He has said that we must be careful, however, not to “clericalize” the role of women because that could feed into an already rampant clericalism for which he has voiced disdain.

But some ask if it is possible to de-clericalize ministry without permitting more universal access to that which is perceived as the center of power. Lip service does little to assuage those who feel left out of the voting that matters.

While some see value in distinguishing gender roles, others fear it is an excuse to keep women as second-class citizens. They argue that presently, power within the Church is reserved for the clerics. If true power is permitted to reside there, it will continue to be the standard by which all other ministry and participation in the Church is measured.

Admitting more members into the clerical state may not be the only solution to broadening and expanding ministerial outreach, but many see it as a necessary step to dismantling a patriarchal structure in which women have not shared equally.

The same woman religious quoted earlier said: “An equal playing field is needed if you want us all to be in the game. Otherwise, just admit you’re more comfortable keeping us on the bench.”

Some have taken issue with Pope Francis’s comments about women. They say he has voiced interesting ideas, but that he has done little to change structures and the lack of gender diversity within the power centers of the Church. That is why his comments about women deacons are such a beacon of hope for many.

With his comments so close to the feast of Pentecost, some are hoping they are indicative of a wind of change continuing to blow.

Sister Carmen Sammut, president of the International Union of Superiors General said, “We are already doing so many things that resemble what a deacon would do, although it would help us to do a bit more service if we were ordained deacons…It is not a question of feminism, it’s a question of our being baptized, that gives us the duty and the right to be part of the decision-making processes.”

It may be encouraging to those longing for more equal participation to recall that Pope Francis comes from a country where women have been in charge for a long time. From Eva Peron to Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, the pope has seen up-close that women are more than up to the task of leadership.

While he has not always agreed with the methodology and conclusions of those particular women, he no doubt has been impressed with the sociopolitical advancement of women in cultures where machismo has been more than evident.

When and how that historical reality may effect change in a patriarchal Church with Francis at the helm remains to be seen.