In late November, when the Church marks the first Sunday of Advent, English-speaking Catholics will have been using a new translation of the Roman Missal, the collection of prayers and other texts used in the Mass, for five years.

Halfway through that run, in the Spring of 2014, Washington’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate commissioned a survey to find out how well the new translation was being received. Out of the priests and lay leaders in the 6,000 parishes surveyed, 51 percent said they either liked the new translation or didn’t notice much difference, while 49 percent said they disliked it.

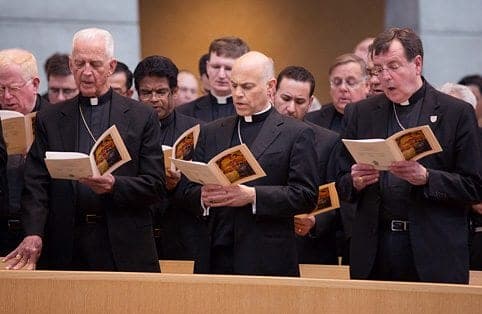

The majority of respondents who disliked it were priests. So, why do so many of the men who have to say these words every day dislike them?

75 percent ”agreed” or “strongly agreed” that some of the language was awkward and distracting, and half the respondents thought the text of the new translation needs urgent revision. When asked if they like the new translation and thought it was an improvement only about 40 percent said “yes.”

The new translation took nearly a decade to produce. It represents countless hours of time by expert and experienced translators. Are they out of touch academics and purists? Did they get it wrong, or are the priests in the trenches at fault for not being flexible and open minded enough to adapt to a new translation?

Are there hidden political or theological agendas at play? Is this a conservative-progressive issue? Has the new translation been foisted on an unwilling presbyterate, or is it simply a matter of hoi polloi not being able or willing to appreciate something noble, beautiful, good and true?

All of these theories may have some truth to them, but I suspect the real reason why the new translation of the missal has been difficult for some to accept is that the translators failed to adequately communicate the principles and objectives of their work.

This, combined with a widespread misunderstanding of the purpose of the Mass itself, are probably the most potent contributors to the ongoing problem.

On November 7, 2008, then-Bishop Allen H. Vigneron of Oakland addressed the Gateway Liturgical Conference in St. Louis, Missouri on the the art of pastoral translation of the liturgy. His paper is available on the website of the USCCB here, and makes for fascinating reading. (Vigneron is now the Archbishop of Detroit.)

Vigneron discusses the overarching principles for translation, as well as considerations of vocabulary and syntax. These norms are taken from the 2001 Vatican document Liturgiam authenticam.

This first set of principles have to do with accuracy and doctrinal faithfulness. With that, there should be no quibble.

The discussion of word choice is where it gets sticky, and it was exactly this problem that most respondents to CARA’s questionnaire found problematic. They said the language was often awkward, distracting or cumbersome. No doubt some of this has to do with the use of archaic language and a lofty turn of phrase, but if the language in the new translation is elevated, it was supposed to be.

Liturgiam authenticam p.25 states, “The translations need to use ‘words of praise and adoration that foster reverence and gratitude in the face of God’s majesty, his power, his mercy and his transcendent nature.’ ”

Do people have trouble with theological terms like “consubstantial” or “became incarnate of the Virgin Mary?” Do ordinary folks raise their eyebrows at phrases like, “We beseech you Almighty Father” or “To you therefore O Merciful Father we make humble prayer and petition…?”

Paragraph 27 of Liturgicam authenticam instructs, “Words and expression which differ from ‘usual and everyday speech,’ even those that are ‘somewhat obsolete,’ rather than being disallowed, are important resources for good translations.”

In other words, the language many find awkward or distracting is intended. That’s not to say that it is intentionally awkward, but that the language of liturgy should be different than the patois of the street because it is otherworldly language.

Literal accuracy is necessary, but language communicates more than the denotative meaning of the words. Something greater than one-to-one meaning is necessary. If this is so, then translating the liturgy is more akin to translating poetry than translating a business contract.

Vigneron explains why.

“The order of salvation brought to us by Christ transcends what is natural…Therefore, the mysteries presented in the liturgical texts are always beyond our registration. Accuracy is always important in translation, in any translation; however, in the case of translating texts which present revelation, the wisest translators will do everything possible to craft texts which express exactly what the original expresses,” he said in 2008.

“This theological ‘meta-principle’ helps us understand why Liturgicam authenticam is so insistent that our first response in translating liturgical texts should not be to make them sound like what we are used to,” Vigneron wrote.

“They present a dimension of reality that is not only beyond the ordinary, but even transcends the most hidden aspects of created reality…This basic meta-principle leads me to conclude that if a translation of the Roman Rite did not to some significant degree strike us as being out of step with our ordinary speech, we should be suspicious of that translation.”

It’s true that the new translation’s long sentences, subordinate phrases and archaic vocabulary is sometimes awkward. I have trouble with them myself, and I have a degree in Speech. I wonder sometimes how our African, Indian, Vietnamese or Polish priests manage.

However, while I am sympathetic to those who find the new translation troublesome, my overall impression is that it is worth making the effort. Articulated properly, the elevated language lifts the soul in worship just as assuredly as a lofty church or the sonorous blast of a pipe organ raises the heart to heaven.