NEW ORLEANS — Among the Mount Tabor experiences of his 57 years as a priest, Msgr. William Bilinsky, now 82, remembers the lock cutters.

The Ukrainian Catholic priest, born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1939 not long after the Nazi invasion of Poland, was back in his parents’ homeland for the first time in his life in 1991, emotionally overwhelmed by the scene unfolding in the dark of night in Mykolaiv, a tiny village 10 miles south of Lviv in western Ukraine.

Bilinsky was in Ukraine as a volunteer translator for retired New Orleans Archbishop Philip M. Hannan, the peripatetic founder of Focus TV who was interviewing Catholics behind the Iron Curtain about how they had struggled to keep the flame of faith alive during a half-century of religious oppression.

At the end of a long day of interviews, a young man found out that Bilinsky was not only a Ukrainian Catholic priest but also a Catholic priest from the U.S.

It was nearly 10 p.m., and the man gathered enough courage to ask Bilinsky if he would come with him in his car.

“As I was in the car, I was thinking to myself, ‘Are you crazy going with some stranger, God knows where? Where is he taking me?'” Bilinsky recalled. “Then, as soon as we got to the entrance of the village, he stopped and gave a signal to somebody, and they started ringing the bells of the church.”

Within minutes of the bells pealing from the steeple of Holy Trinity Ukrainian Catholic Church, hundreds of villagers walked up the hill to the town square for the first liturgy celebrated inside the church since 1946.

“There was a lock on the door, and they took lock cutters and broke it open,” Bilinsky told the Clarion Herald, New Orleans’ archdiocesan newspaper. “It was dusty. The vestments were not in the best shape.

“And the other problem was all of the liturgical books were written in the church’s Slavonic language, which is the old language we used to use prior to the Second Vatican Council.”

The church was a time capsule.

Five hundred people, standing, could squeeze inside the church. There were no pews.

Before the liturgy, an elderly sacristan asked what the priest needed.

“Some bread and wine,” Bilinsky said.

“Our wine is no good, but we have very good vodka,” the man said initially, before asking a few friends to find some suitable wine.

And he brought the priest leavened bread, which is what Eastern-rite Catholics use for holy Communion. But it was raisin bread.

“Instead of arguing with him, I said to myself, ‘You know what, Lord? You can make your way around the raisins,'” Bilinsky recalled. “I cut up the bread into little cubes and tried to make sure there weren’t any raisins in there.”

As Bilinsky began the liturgy, he noticed two elderly men walk into the sanctuary wearing vestments.

“They were old priests who had been in the underground church,” he said.

After proclaiming the Gospel, Bilinsky climbed the steps of the elevated ambo.

“It was one of those old European pulpits where you walk way up, and I preached, but I didn’t preach too long,” he said. “As I finished and I was walking down the steps, the sacristan came up to me and said, ‘Too short. Preach some more!’ So I went back up there and preached some more.”

At the end of the liturgy, Bilinsky walked outside into the square, where there were hundreds more Catholics who couldn’t get inside the church. He hopped into a pickup truck that had a battery-operated megaphone and preached another sermon.

Earlier in the day, Bilinsky had been translating for the local archbishop in Lviv during his interview with Hannan.

The Ukrainian archbishop held out his hands.

“He had no fingernails,” Bilinsky said. “He had been in prison and they pulled his nails out.”

When the archbishop found out Bilinsky was going to Mykolaiv, he gave him chrism along with a special mission to baptize and confirm anyone who asked. The Eastern Catholic Church confers confirmation at the same time as baptism.

“When you run into people, they may ask you to baptize their children, so don’t worry about the paperwork,” the archbishop told him. “I know how you Americans are with paperwork. You just baptize and confirm, and we’ll worry about it later.”

After the liturgy and throughout the predawn hours, Bilinsky went from house to house, baptizing and confirming.

“I would say, ‘What is the child’s name?’ and they would say, ‘What’s your name?’ so I told them my name was ‘Wasyl’ for Basil, because I was baptized on the feast of St. Basil the Great,” Bilinsky said. “If it was a girl, they went with ‘Wasylina.’ I’ve got more kids named after me in that town than you could imagine.”

When Bilinsky returned to Lviv, he walked into the Cathedral of St. George, the mother church for Ukrainian Catholics that had just been taken back from the Russian Orthodox Church, which had ties to the Soviet Union.

“I fell to my knees at the sanctuary and just cried,” he said.

Inside the cathedral, a few Redemptorist brothers dressed in their habits who had emerged from the underground were giving religious instruction to children in the choir loft.

“We are re-catechizing the children,” they told Bilinsky.

Bilinsky walked up the steps and, for the next two hours, taught them the faith.

“The next day, one of the Redemptorist brothers came over to my hotel to give me a gift,” Bilinsky said. “It was this church, made by the children out of stick matches.”

Somehow, Bilinsky was able to get it home as a lasting reminder of light conquering the darkness. He has it in a small chapel that he keeps in his home, right next to an icon of Mary holding tightly to the baby Jesus inside a prison.

“It’s called the ‘Church in Chains,'” he said. “Mary and Jesus are in a jail cell.”

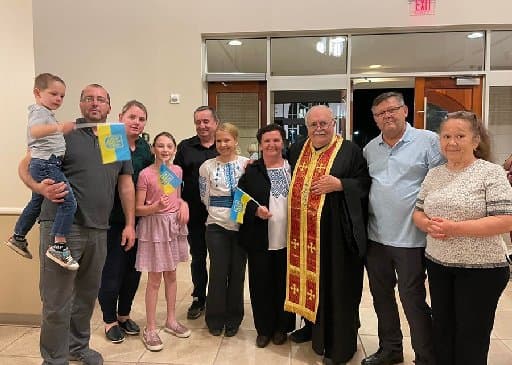

Bilinsky has been raising money to send to three Ukrainian Catholic priests who came to New Orleans for three summers when they were still seminarians.

He said Mary Queen of Peace Parish in Mandeville, Louisiana, and St. Joseph Seminary College had welcomed them as they studied and did a few odd jobs to earn money for their families.

Now, the three priests and their respective communities are under siege.

Bilinsky also has a cousin on his father’s side in western Ukraine, in her 70s, who has a grandson and daughter-in-law, both physicians. The grandson was in Poland but went back into Ukraine to help provide medical care.

Bilinsky is praying for a peaceful resolution, but he knows that will take a miracle.

“There is going to be a bloody end to this, more bloody than it has been,” he said. “The Ukrainians are not going to go back (to subjugation).”

– – –

Finney is executive editor/general manager of the Clarion Herald, newspaper of the Archdiocese of New Orleans.