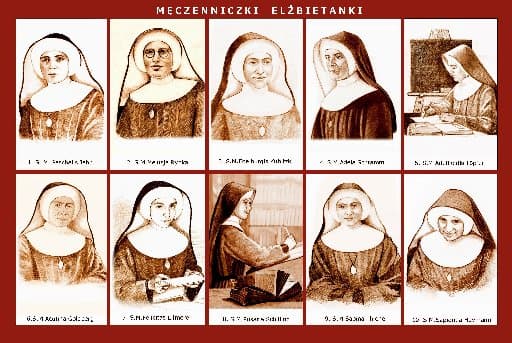

WARSAW, Poland — Senior Catholics see the beatification of 10 Polish nuns murdered by Russian soldiers at the end of World War II as highlighting the need for radical Christian witness while offering a prophetic reminder of current sufferings in Ukraine.

“Every beatification or canonization of any nun is a cause of joy, while every example of radical commitment, including martyrdom, has huge value,” said Mother Jolanta Olech, secretary-general of Poland’s Conference of Higher Female Superiors.

“What’s occurring today in Ukraine, however, with similar crimes committed every day, shows the importance of testimonies like these. I’m certain martyrs are being created there now about whom we’ll learn in the future,” the Ursuline sister told Catholic News Service amid preparations for the June 11 beatification of Congregation of Sisters of St. Elizabeth members.

Meanwhile, Archbishop Józef Kupny of Wroclaw, Poland, said the pope’s approval of the beatification in June 2021 turned out to be “prophetic” for Poland, Ukraine and the wider world.

“In their faces, we see the faces of women and children now falling victim to similar aggression by Russian soldiers,” he wrote in a May 29 pastoral letter.

“At one time, it seemed we could only talk about violence, aggression and the killing of innocent people in the past tense, hoping the events these sisters witnessed would never return,” he said.

“No one predicted our brothers and sisters in Ukraine would experience the same fate. Yet today, we must painfully concede that we were wrong. Evil still exists and takes its tragic toll. The world has apparently failed to learn from history,” the letter said.

Prayers for peace in Ukraine will be offered during the ceremony at the Wroclaw cathedral, he added.

The St. Elizabeth order, founded in 19th-century Silesia to nurse cholera and typhus victims, was one of many facing brutality from the Soviet Army during its victorious 1944-1945 sweep across Poland, which had already lost a fifth of its population, including most of its Jewish minority, during six years of Nazi occupation.

Atrocities were most common against women religious of German origin, who were among millions of civilians expelled as lands in eastern Germany were incorporated into Poland in exchange for Polish lands annexed by the Soviet Union in the east.

The oldest nun, 70-year-old Sister Sapientia Heymann, had spent the war caring for sick and elderly nuns at Nysa, Poland. She was shot by drunken Russian soldiers while attempting to protect fellow sisters from rape.

The youngest, Sister Paschalis Jahn, had joined the order in 1937, also nursing the old and infirm. Before making her final vows, she had been evacuated to Sobotina in nearby Czech Moravia. She was 29 when apprehended by a Russian soldier on May 11, 1945, four days after the war’s official end, and shot through the heart for resisting his advances.

In his letter, Kupny said the story of the nuns contained “terrifying descriptions of evil and cruelty,” and had left “wounds that cannot fail to move and should never be forgotten.”

The martyred sisters, he added, had offered “a signpost for people in the 21st century” by remaining “faithful to their vows and the values they believed in,” without expecting personal recognition.

Sister Acutina Goldberg, born into a peasant family, had taught children and war orphans before escaping from Lubiaz, Poland, with a group of girls, only to be caught by drunken Russian soldiers and shot in a field while protecting her charges.

Sister Edelburgis Kubitzki, a 40-year-old ambulance nurse, attempted to escape rape by hiding with other nuns inside a chapel at Zary, Poland, but was beaten and shot at least a dozen times when troops entered the building Feb. 20, 1945.

Another nun, Sister Felicitas Ellmerer, 56, took refuge in her order’s refectory at Nysa, after Russian soldiers profaned the chapel and drank wine from its liturgical vessels while shouting “Long live Christ the King!” She was shot by a Russian trooper, who stomped on her head to finish her off.

Sister Adela Schramm, 40, a convent superior at Godzieszow, Poland, had cared for wounded soldiers and displaced civilians when she was seized by Russians while sheltering in a farm attic and shot and dumped in a bomb crater following a long struggle.

Wroclaw-born Sister Rosaria Schilling, 36, who was raised as a Protestant, hid with other nuns in an air-raid shelter at Nowogrodek, but was dragged out, raped and shot by a group of 30 soldiers.

Others to be beatified are Sister Melusja Rybka, Sister Adela Schramm and Sister Adelheidis Töpfer.

In a June 1 message to CNS, the nuns’ postulator, Sister Miriam Zajac, said at least 100 St. Elizabeth sisters had been killed by Red Army troops, some disappearing without trace. She said the cases of the 10 martyrs had been detailed and documented from eyewitnesses.

She noted that no Russian soldiers had ever faced sanction for violence and rape, which were “used as an element of military strategy.” Establishing the truth, she said, was not intended as “an act of revenge or reckoning,” but as a necessity for “overcoming the traumas of the past.”

The “heroic attitude” of the nuns could provide a “model and impulse” for contemporary women facing a violation of dignity, as well as for married couples threatened by infidelity and victims of sexual abuse, Zajac said.

“Our order experienced exceptionally hurtful brutality and lawlessness from those came to liberate us but turned out to be barbarians — for long years, we had to keep silent about their martyrdom, and couldn’t speak or write about the Red Army’s bestial behavior,” she said.

“Whenever Christ isn’t accepted, with the commandments and values he left us, it always leads to criminal totalitarian systems, genocide and the collapse of morality and culture — as we now see among our neighbors in Ukraine, where the Russian army is doing the same as Red Army soldiers did in 1945, playing out before our eyes the same scenes with the same directors.”