As we seek to know more about prayer, we can turn to the Catechism of the Catholic Church. While there are many primary sources on prayer and many secondary sources that give helpful summaries of prayer and the spiritual life, the Catechism is second to none in its conciseness and summary of the principal points of the spiritual life.

In Part Four of the Catechism, the Church cuts through a lot of the more confusing aspects of the spiritual life and truly gives us a mysticism with eyes wide open. It makes the riches of the mystical life very digestible and easier to grasp.

After an introduction that presents prayer as a gift, covenant, and communion, Part Four of the Catechism moves to the first of only two sections.

The first of section one’s three chapters is on “the revelation of prayer – the universal call to prayer.” The chapter starts by balancing two essential truths: “Man is in search of God,” and “God calls man first.” In summary, the Catechism teaches us: “In prayer, the faithful God’s initiative of love always comes first; our own first step is always a response.”

The search for God by human beings is always preceded by God’s search for us. God is summoning all his children to himself. He is looking for us. Each person has to hear the call of God and begin their own journey to him. Such a search for God includes prayer and becomes “a reciprocal call.” God calls to us. When we pray, we call out to him.

The search for God is not without its bumps, trials, doubts, and difficulties. The Catechism calls the mutual search of God for man and man for God “a covenant drama.” Such a drama engages the spiritual heart of each person. It involves a crying out to God in prayer. The drama helps us to see the two sides of the mystery of prayer.

The Catechism then tells us that the drama of prayer “unfolds throughout the whole history of salvation.” It uses this assertion as a springboard to dive into the Sacred Scriptures and begin a summary of the revelation of prayer through the ages.

The Catechism tells us that the revelation of prayer in the Old Testament is the time period between the fall of humanity and its restoration.

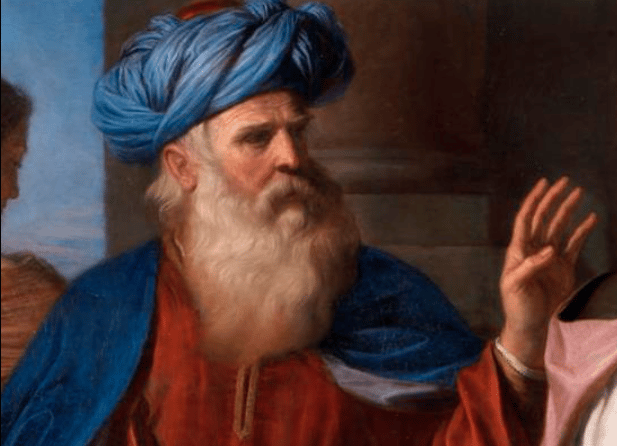

Within this context, the Catechism highlights creation as a source of prayer. It mentions the sacrifice of Abel and Noah, which were offerings from the creation given to humanity by God. While the early portions of Genesis can teach us about prayer, the Catechism highlights and points us to the patriarch Abraham: “In his indefectible covenant with every living creature, God has always called people to prayer. But it is above all beginning with our father Abraham that prayer is revealed in the Old Testament.”

The person of Abraham stands out in salvation history. He is the recipient of God’s promise and offers to God the prayer of faith.

The Catechism stresses the obedience of Abraham’s heart to the will of God. The Church highlights that – if we want to prayer – then our hearts must be willing to submit to the inclinations of God within it: “Such attentiveness of the heart, whose decisions are made according to God’s will, is essential to prayer, while the words used count only in relation to it.”

It’s important to point out the Catechism’s placement of the actual words we speak. As indicated, the words we use are only helpful in relation to the attentiveness of our hearts. If we seek to pray, but close off our hearts to the will of God, then we can easily fall into empty prayer, which is a mere “lip service” to God without meaning or substance.

The Catechism shows Abraham to be a silent man, a man of prayer by deeds. He builds altars and looks for opportunities to draw close to God. Only after such actions, does he speak and express his disappointment that God has not fulfilled his promise yet. Abraham wants a son, a son that God promised him.

Abraham vents before God and asks why there has been a delay. God is patient with him and teaches him about the importance of waiting and trusting. Abraham accepts the instruction and wants to obey and trust. The Catechism points out: “Thus one aspect of the drama of prayer appears from the beginning: The test of faith in the fidelity of God.”

If we are going to pray, we need to be willing to trust in the faithfulness of God. As we cry out to him in prayer, we must be confident in his goodness and be willing to wait for his answers.

Such a posture of trust and submission fly in the face of the messaging of our fallen world. We are told to trust only ourselves and to make things happen on our own terms. The more we temper such influences, the more we can hear divine wisdom and open our hearts to prayer.