The first time I encountered the charismatic Irish priest, poet, and philosopher John O’Donohue, he was online talking about the upside of last rites.

“Usually people are so surprised that ‘That was it,’” he said. There is no more to their life. That’s particularly true of those who never lived the life they wanted or thought they deserved. Those who postponed life, allowed themselves to be contained by other people’s expectations. Those who dreamed of a future that never came. “Their life was squandered,” he said.

So the upsides, then?

A deathbed is “the loveliest place to be if you’re helping someone to die who has really lived,” said O’Donohue, remembering one wild and roguish character. After he finished with the sacrament, he asked the man, “What would you say about the whole [life] thing now that you’re about to leave it?” A sly smile crossed the man’s face. He told O’Donohue: “By Jesus, I knocked a hell of a squeeze out of it.” Two minutes later, he was gone.

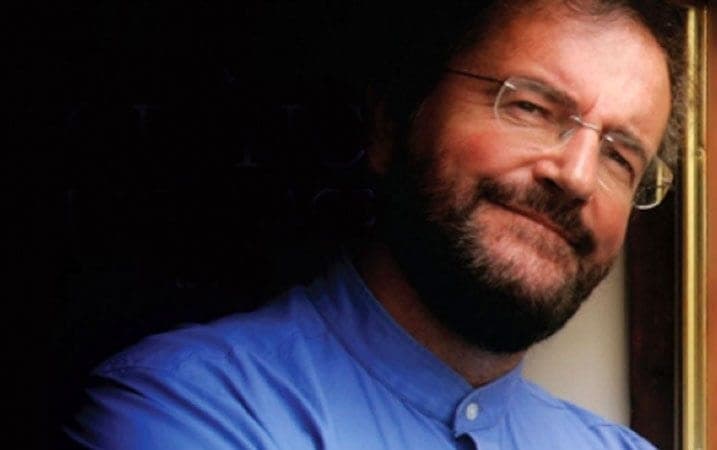

John O’Donohue became famous in the United States and in Ireland partly because he believed we could all transform our fear of death — and that enables us to fear little else. We don’t know how O’Donohue himself fared facing his own death eight years ago last month. He died in his sleep. The cause remains uncertain. He was just 52.

But his ideas about transforming our fear have to do with living more fully, getting our own big “squeeze” out of life. “The Glory of God is the human being fully alive.” That’s a favorite O’Donohue quote from the early Church father, Irenaeus.

His ideas have to do as well with learning to live in an uncommon way for our 21st-century, wired and weary rat race: seeking more silence and solitude, slowing down, living mindfully, paying attention to the beauty we do not see.

Some of that sounds quite new age-y, I realize. Yet his writing does not. Some is, in fact, heavy-lifting philosophy. His second book, “Eternal Echoes” (1998), delves into the theories of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Jean-Paul Sartre on post-modern malaise and our need to belong. Perhaps a more apt description of his books, essays, poetry, and blessings would be this: expressions of wisdom and perspective that, once read, feel very familiar and sensible. You just haven’t seen them written quite O’Donohue’s way before.

And there’s simply a soul-soothing simplicity and gentleness to the language of his first book, the surprise 1997 bestseller “Anam Cara: (Soul Friend) a Book of Celtic Wisdom.” Here’s how he starts it:

It’s strange to be here. The mystery never leaves you alone.

Then he guides you through that wisdom. The mystery of friendship. A spirituality of the senses. The luminosity of solitude. The last part of the book returns to a favorite theme, death as the root of our fears. But he offers, again, the upside of departing this world: the beautiful death of a young mother who’d been petrified until assured by her priest, over and over, that she was going home, that the “God who had sent her would welcome her and embrace her and take her so gently and lovingly home.” That the children she was leaving would still know her to be near, loving, and guiding.

O’Donohue speaks, too, of the dying he’s helped who lived hard, tight, and unyielding lives, “knuckled into themselves.” Yet within days of their deaths, “I’d see them loosen up and a kind of buried beauty surface that they’d never allowed to enjoy themselves, [that] brought a radiance to their face. Suddenly there was a recognition that their time was over and that their way of being could no longer help them, that there was another way of being [that] became transformative.”

John O’Donohue spent 19 years as a Catholic priest before leaving over disagreements with the hierarchy. He was the son of a housewife and a stonemason whom he called “the holiest man I ever met, priests included.” He grew up in Connemara, one of the most haunting and unspoiled parts of Ireland’s west coast, and he talks about the impact of that childhood landscape, and its quiet, on his spiritual life.

“It makes a huge difference when you wake in the morning and come out of the house into a landscape that is just as much if not more alive than you but in a totally different form,” he told “On Being’s” Krista Tippet in one of his last interviews before he died.

Beauty is not a luxury, not something owned by the wealthy or elite, but something available to us all that “ennobles the heart and reminds us of the infinity that is in us. We feel most alive in the present of what is beautiful,” he said. “It returns us to our highest selves,” and points us toward God.

He also spoke about the relationship between his early life, much of it spent in silence and solitude, and his sense of time. “Still in the West of Ireland there’s a sense that there is time for things. One of the huge difficulties of modern life is the way time has become the enemy. Stress is a perverted relationship to time. So rather than be a subject of your own time you’ve become the target and victim of time. At the end of the day [you’ve had] not a true moment to yourself.”

There are numerous videos online of O’Donohue, a handsome man with a glorious brogue, reading his poetry or his blessings or expounding on Ireland, love, faith, God. “Anam Cara,” broken up into small sections two or three pages long, is probably his most accessible book. Each little section, “The Trap of False Belonging” or “The Passionate Heart Never Ages,” is worthy of a meditation. You can read a little every day.

And here, for you poetry fans, is a taste of O’Donohue from his poem “Beannacht,” or blessing:

On the Day when

the weight deadens

on your shoulders

and you stumble,

may the clay dance

to balance you.And when your eyes

Freeze behind

The gray window

And the ghost of loss

gets in to you,

may a flock of colors,

indigo, red, green

and azure blue

come to awaken in you

a meadow of delight…