To say that David Albert Jones enjoys a “certain standing” within the field of Catholic bioethics would almost certainly be putting things mildly. Since 2010 he’s directed the Anscombe Bioethics Centre at Oxford in the UK, one of most influential think tanks on such matters in the world.

Jones is also a key adviser to both the English and the European bishops. He’s a member of the Health and Social Care Advisory Group and the Department of Christian Responsibility and Citizenship of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, and is also a member of the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the EU (COMECE) Working Group on Ethics in Research and Medicine.

Of late Jones’s interests have taken a turn into matters of gender identity, reflecting a new surge of attention fueled, to a great extent, by larger social and cultural developments. The following is a transcript of his exchange with Crux.

Camosy: Until now your work has mainly been in Catholic bioethics, on issues such as abortion and euthanasia. Why did you decide to engage with the issue of gender identity?

Jones: I came across the concept of gender identity first as a bioethical issue. People asked me how Catholics should regard the ethics of gender reassignment surgery and the ethics of prescribing hormones or hormone blockers. In response, I wrote a brief statement on bioethical principles and some clinical aspects.

In writing this I was struck by the weakness of the evidence base for current clinical practice on “gender dysphoria” (a medical term referring to the distress caused by a mismatch between natal biological sex and experienced gender identity). At the same time, I was very wary of the reliance of some Catholic commentators on that minority of clinicians who are equally certain of the opposite opinion – that current clinical practice is harmful, especially to children. This led me to write a short article criticizing a statement on “gender ideology” produced by a group called the American College of Pediatricians.

I concluded that “there is an urgent need for the Church to develop… theological resources, in dialogue with clinicians and with people experiencing gender incongruence.” However, my own understanding was still theoretical, indirect, and mainly focused on clinical aspects rather than on the experience of persons with a divergent sense of gender identity.

On the basis of what I had written, I was asked to help develop pastoral and theological resources in this area. This gave me the opportunity to seek out transgender people who were practicing Catholics to ask them about their experiences and what they felt would be helpful. I also spoke to canon lawyers, educationalists, and priests with experience accompanying transgender people but the most important thing for me was to listen to people who were seeking to live their faith while accepting their deep-rooted sense of gender identity.

Despite the very personal nature of the journey that each had made, I found a great willingness to talk and an appreciation of my attempts to listen, as one person said to me, “thank you for speaking to us and not just about us.”

What have you found from your research? What does the Church teach about gender identity and about gender reassignment surgery? Why have Catholic hospitals sometimes refused to perform such surgery?

My investigation of the issue of gender identity has revealed to me how little I understood this aspect of human existence. It is not simple and if you think it is simple you are probably misunderstanding it. It also reminded me how we all carry with us unexamined cultural assumptions through which we express Christian doctrine or frame scientific and philosophical enquiry.

I began the task of teasing apart what is true and authoritative in the Catholic tradition regarding sex and gender and what is unwarranted cultural assumption. At the same time, I sought to attend carefully to the voices of those whose experience of gender identity challenges these assumptions. Recently these strands of work have been brought together as a project to support transgender people in the Church, hosted by St Mary’s University in Twickenham, London.

One practical issue for Catholic hospitals is whether they should offer gender reassignment surgery. I examined this question in an article recently published in Theological Studies. Though gender reassignment surgery has been practiced in Europe since the 1950s and in the United States since the 1960s it has never been mentioned in any official teaching document of the Church. It has not been mentioned explicitly in any papal address or encyclical. It is not mentioned in the Catechism of the Catholic Church nor in any statement by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

In the absence of any official teaching most Catholic moral theologians, where they have considered the question, have taken one of two views. Some have characterised such surgery as mutilation, direct harm to the body, and therefore as incompatible with Catholic medical ethics. Others have argued that such surgery could be considered justifiable, if it helps alleviate the extreme distress of gender dysphoria. However, typically, this second group of theologians have cast doubt on whether such surgery is effective in providing long-term relief.

My own view is that surgery may alleviate the suffering of some patients. However, I cannot see how gender reassignment surgery, where this causes sterility, is compatible with the ethical principles of the Catholic tradition. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that, as yet, there is no explicit and authoritative Catholic teaching precisely on this question.

Furthermore, if Catholic hospitals do not offer gender reassignment surgery this must not be because of a reluctance to care for transgender patients. Any such refusal, to be ethical, must refer not to the person to be treated but only to the nature of the procedure.

Pope Francis and Catholic bishops in many countries have taught that a gender ideology has emerged that is harmful to society in general and to children in particular. Do you agree?

The movement for greater acceptance of transgender people is part of a much larger debate about sex and gender in society. On these questions there is more than one secular view, more than one religious view, and the Catholic view, while constant in its essentials, has developed over time.

For example, in the twentieth century, the teaching of the Church has shown a greater appreciation of the equal dignity of husband and wife within marriage.

In their reflections on the equal but in some ways distinct roles of men and women in the family and in society, Pope Francis, and several bishops’ conferences have called attention to some contemporary ideas that are potentially harmful. Chief among these are a denial of the complementarity of male and female, a failure to recognise the goodness of the body and the unity of body and soul, a radical separation of the concepts of sex and gender, finally, the idea that gender identity is or ought to be a matter of personal choice.

These errors, grouped together under the term “gender theory” (teoria del gender) or “gender ideology” (ideologia del genere), can be traced back to certain strands of feminism. Nevertheless, to recognise these as errors is not to reject feminism as such, “If certain forms of feminism have arisen which we must consider inadequate, we must nonetheless see in the women’s movement the working of the Spirit for a clearer recognition of the dignity and rights of women” (Pope Francis Amoris Laetitia).

It is also important to note that the focus of this papal teaching is on various errors of a theoretical kind and the way these errors have been promoted by governments and educational bodies. It is not directed at the situation of people who experience a consistent, persistent and insistent sense of identity incongruent with their natal sex.

In this regard, it is worth quoting a recent statement by the LGBT+ Catholics Westminster Pastoral Council:

“Being transgender does not mean that someone wishes to abolish gender or sexual difference; in fact many transgender people report feeling great joy and peace once their bodies and gender identities are aligned. The argument that gender is purely a social construct is often used to delegitimize, rather than support, transgender identities. Gender is not a matter of individual choice for transgender people any more than it is for cisgender (i.e. not transgender) people. Although it is currently not known why some people are transgender, current research suggests that genetics, hormones and environment all play a role.”

The very idea of transitioning from male to female (or vice versa) does not contradict but rather presupposes the existence of a gender binary. Hence, while it is important to accept the positive teaching of the pope and bishops on gender complementarity, it should not be assumed that this teaching is necessarily incompatible with affirming the gender identity of trans people.

You’ve written that gender transition could be compatible with a Catholic anthropology, but one might ask how denying your own God-given sexual identity can be compatible with a Catholic understanding of the body, marriage, and the Divinely created complementarity of male and female?

When we try to make sense of diverse expressions of gender identity it is natural to reach for analogies with other issues. Transgender identity is seen as being like feminist ideas of social gender roles, or as like sexual orientation (hence the initialism LGBT), or like physiological divergences of sexual development (popularly known as “intersex” conditions), or as a type of body dysmorphia (like anorexia). I have argued that incongruent gender identity is like (but also unlike) each of these phenomena.

Legal or social changes of gender identity are also like (and unlike) the legal and social practice of adoption. An adopted son or daughter is a true son or daughter, by adoption (and this true relationship is invoked in Scripture as a model for our relationship with God by grace – Galatians 4.5). An adopted child does not deny the reality of his or her natal biological identity, but he or she is assigned a new identity that has a social and legal reality in order to address his or her needs. Sophie-Grace Chappell, an academic philosopher sympathetic to the Catholic intellectual tradition, who is herself trans, has also made use of this analogy (while acknowledging its limits).

If you’re an adoptive parent, you’re a parent for most purposes and no one sensible scratches their head over it – they don’t decree that you can’t sit on school parents’ councils, or see it as somehow dangerous or threatening or undermining of “real parents” or dishonest or deceptive or delusional or a symptom of mental illness or a piece of embarrassing and pathetic public make-believe…”transwomen are to women as adoptive parents are to parents.”

How, in your view, can faithful Catholics show respect and pastoral concern for trans people while also honoring what they believe to be true about sex and gender?

No pastoral approach is sustainable if it is not honest and informed by a commitment to seek what is true and good. This commitment will include the acknowledgement of sin in ourselves and in the social structures that shape our world.

Discernment is needed, however, to distinguish what is sin and needs to be renounced (though perhaps this will only be accomplished by steps) and what is not sin but is an element of diverse and complex human experience. In the case of divergent gender identity, we should not assume, as perhaps the question seems to assume, that someone expressing a deep-seated sense of gender identity is doing something sinful or objectively disordered. On the contrary, the person may be accepting his or her gender identity as something given by God.

There are difficult moral issues related to incongruent gender identity, issues concerning marriage, sexual ethics and surgery. Moral discernment is needed to know what can be endorsed, what cannot be endorsed but might, in certain circumstances, be tolerated, and what should be challenged.

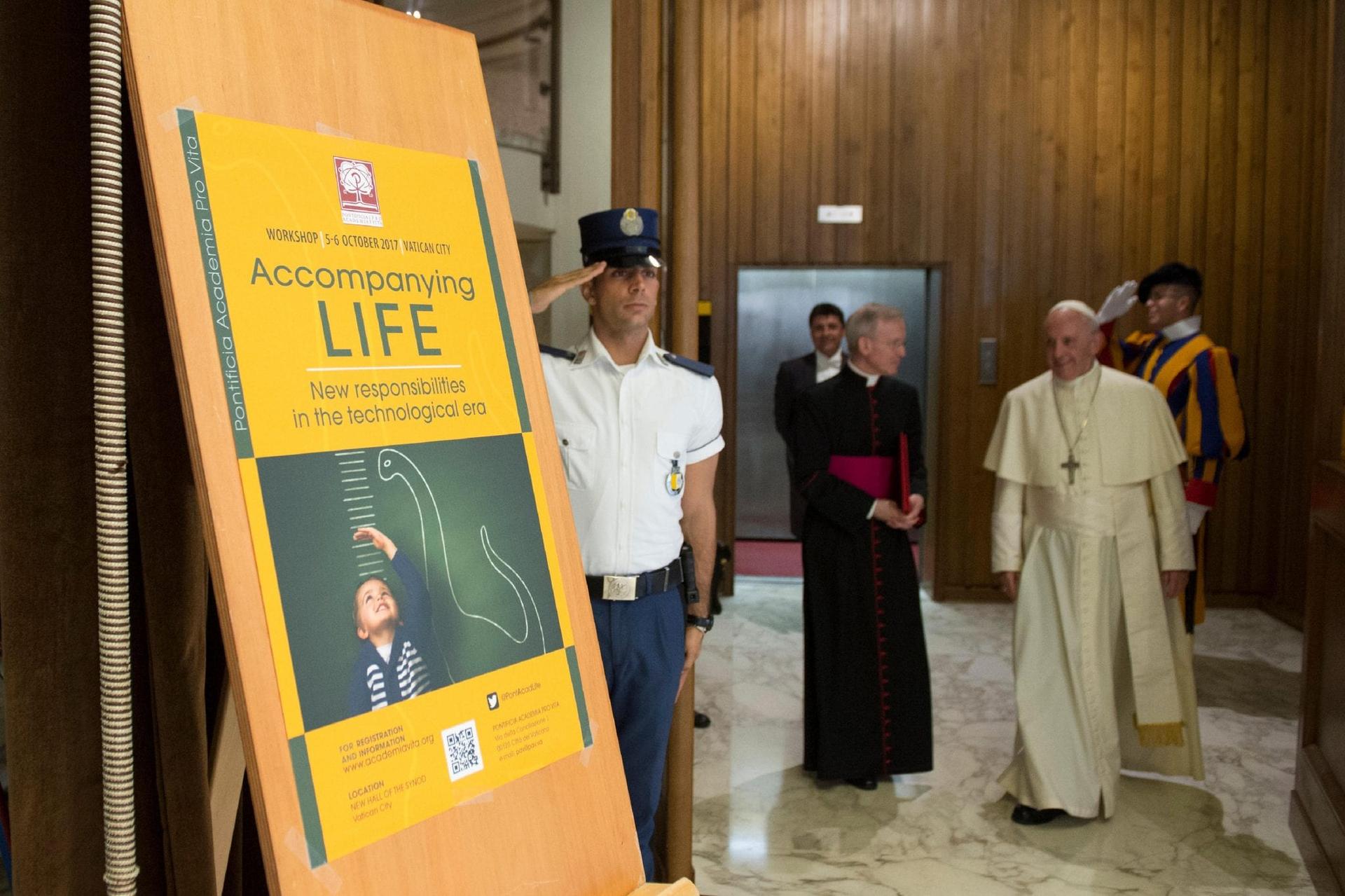

However, prior to discernment comes accompaniment. Pope Francis, talking about the pastoral support of trans people said, “for every case welcome it, accompany it, look into it, discern and integrate it. This is what Jesus would do today.” Pastoral guidance in this area, if it is to be wise and helpful, will be the fruit of accompaniment and informed by the experience of the people the guidance exists to support. It should arise from “speaking with” and not just be “speaking about” Catholics with a divergent sense of gender identity.

A final pastoral reflection: Pope Francis, who more than any other pope has called attention to the dangers of “gender theory,” consistently uses gender pronouns that reflect the person’s sense of identity. He refers to a person who was born a girl as a “man,” as “he,” and as “he, who had been she, but is he.”

Catholic pastoral practice must begin with welcome and the first sign of welcome is how we address someone. There is nothing un-Catholic about the use of names and pronouns that reflect a person’s sense of identity.

Professor David Albert Jones is Research Fellow at St Mary’s University, Twickenham and director of the Anscombe Bioethics Centre in Oxford, though the views expressed here are his own and should not be attributed to either institution.