Editor’s Note: This is part one of a two-part interview with Dominican Father Paul Murray. Part two will be published shortly.

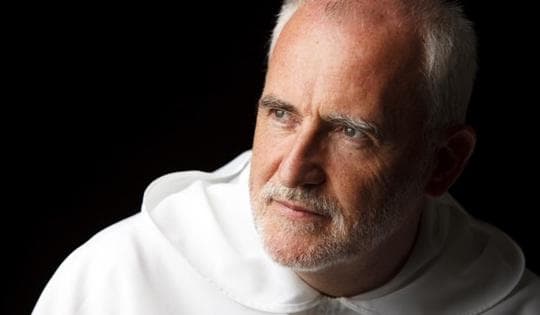

ROME – Dominican Father Paul Murray is one of English-language Catholicism’s most prominent contemporary theologians and poets. Born in Northern Ireland in 1947, he joined the Irish Dominican Province in 1966 and was ordained in 1973.

Murray has published five collections of poetry, including Scars: Essays, Poems, and Meditations on Affliction, and most recently, Stones and Stars in 2013, in addition to numerous books and essays on theology. He teaches the literature of the mystical tradition at Rome’s Dominican-run University of St. Thomas Aquinas, universally known as the “Angelicum.”

Crux recently reached out to Murray via email to talk about the spiritual significance and fallout of the coronavirus pandemic. The following are Murray’s responses.

Crux: Is the obvious historical parallel to what we’re experiencing the plague, or is that too facile? What does the situation call to mind for you?

Murray: I’d say there are real parallels between what is happening today with the present pandemic and the plagues and pandemics of the past. What’s more, there are things which we can learn from the wisdom of the Christian response in those early centuries.

I have particularly in mind here the response of St. Cyprian, the Bishop of Carthage, to the pandemic which afflicted the Roman Empire in the third century. It’s said that in Rome, at the height of the outbreak, approximately 5,000 people were dying every day. This pestilence was the second of two pandemics which marked the very first transfers from animal hosts to humanity, something that’s characteristic, of course, of the present corona virus.

St. Cyprian, while recognizing the appalling nature of the pandemic, saw it first and last as an opportunity for the strengthening of faith and hope. In his opinion the situation called for enormous courage and enormous trust.

“What a grandeur of spirit it is,” he declared, “to stand up with living faith before “the onsets of devastation and death” and, instead of being paralyzed by fear, to “embrace the benefit of the occasion.” By this Cyprian meant the opportunity for Christian believers to manifest to those around them a willingness to bear the cross of the moment and, at whatever cost, to do everything they could to assist those in the greatest need.

But why had this pestilence come upon the world? If God really cares for us, where is God to be found in all of these catastrophes? The response Christian spirituality gives to this question – and it is the question of all questions – possesses little or nothing of the bright cleverness of a well-argued, academic answer.

Instead, with humility and reverence, all four Gospels together, and with them the great spiritual tradition, direct our attention first and last to the figure of Christ Jesus on the cross. It is to that presence, and not to some kind of abstract, indifferent deity, that we are encouraged to bring all our doubts, and all our anguished questions.

And while we ourselves are engaged in searching for answers, while we are presuming to put our questions to God, there is a sense in which, St Cyprian reminds us, God is questioning us, God is engaged in probing and searching our hearts.

Cyprian writes: “How fitting, how necessary it is that this plague and pestilence which seems horrible and deadly, searches out the justice of each and every one, and examines the mind of the human race, asking whether or not those who are healthy are caring for the sick, whether relatives dutifully love their kinsmen as they should, and whether doctors are refusing to abandon the afflicted in their charge.”

Many bishops, faced with the suspension of public Mass, have been emphasizing “spiritual communion.” In light of the Catholic spiritual tradition, are there any reflections you’d like to share?

First of all, let me state the obvious: for countless thousands of Catholics today it is nothing less than a tragedy to find themselves unable to attend Mass, and so unable to receive Christ in Holy Communion. In light of this unhappy situation the advice now being offered by the bishops for all those at present in isolation to begin practicing what has been traditionally called “spiritual communion” is unquestionably wise.

Of course, as a spiritual practice, it is nothing as great as actual attendance at Mass. And it may well appear, at first, as a very poor substitute indeed. But “spiritual communion” is in itself a tremendous grace, as has been attested by saints and theologians over the centuries. St Teresa of Avila, for example, has this to say: “When you do not receive communion, and you do not attend Mass, you can make a spiritual communion which is a most beneficial practice; by it the love of Christ will be greatly impressed upon you.”

Spiritual communion, when it is authentic, always has at its core a desire to be one with Christ in the Eucharist. Desire of this kind I was privileged to witness once in the life of a prisoner on death row.

Catholic Mass had not been celebrated in that particular part of the prison for several years. The prisoner in question, a Catholic, struck me as a very ordinary guy. All the more striking, therefore, was the strength, the force, of his desire to attend Mass and to receive the Eucharist. He asked the authorities of the prison that Mass be celebrated at least on Sundays, and he kept on asking although ordered to stop. After some considerable time, permission was granted, but only after he had suffered a great deal.

When, some months later, I celebrated Mass for him and for a small number of other prisoners on Death Row, I noticed that he wept at the moment he received the host. And, just after the Mass, when I spoke to him through the bars, I noticed that once again tears were flowing down his cheeks. He said to me: “It’s only when you are deprived of something that you realize how precious it is!”

Are there any particular stories from the Christian past, stories from the lives of the saints, for example, which stand out for you as examples of “spiritual communion”?

There are, of course, a great number of stories which could be recalled in this context. But the story which, for me, most stands out is the story of the imprisonment of the Carmelite poet and mystic St John of the Cross. Captured and taken from his priory, John was forced to live in appalling conditions, beaten regularly, and almost starved to death. He appealed to the authorities to be given permission to attend Mass, but this request was refused.

Astonishingly, it was in these dreadful conditions that John began to write what is arguably the greatest mystical poetry in the Catholic tradition. One of the poems speaks of the fountain of living water welling up in the heart of the believer, but always within the darkness of faith:

“How well I know the spring that brims and flows, although by night!” The poem’s brief concluding stanzas constitute a meditation on the Eucharist. The first begins: “This eternal fountain is concealed from sight / Within this living bread to give us life.” Here, although John is cut off from the Mass, he finds that in a real way he is present to the mystery, his whole attention focused on the Eucharist. The final stanza reads: “I long for this, the living fountain-head, / I see it here within the living bread, / although by night.”

Over the centuries, Christian men and women, when deprived of the sacraments, discovered in their need some rather surprising ways of practicing spiritual communion. A bishop from Bulgaria told me many years ago that, during a certain period of Communist persecution in his country, almost all the priests of his diocese were either dead or in prison. As a result, the people of God, when they wanted to go to Confession, would go to the graves of the priests, and it is there they would confess their sins to God.