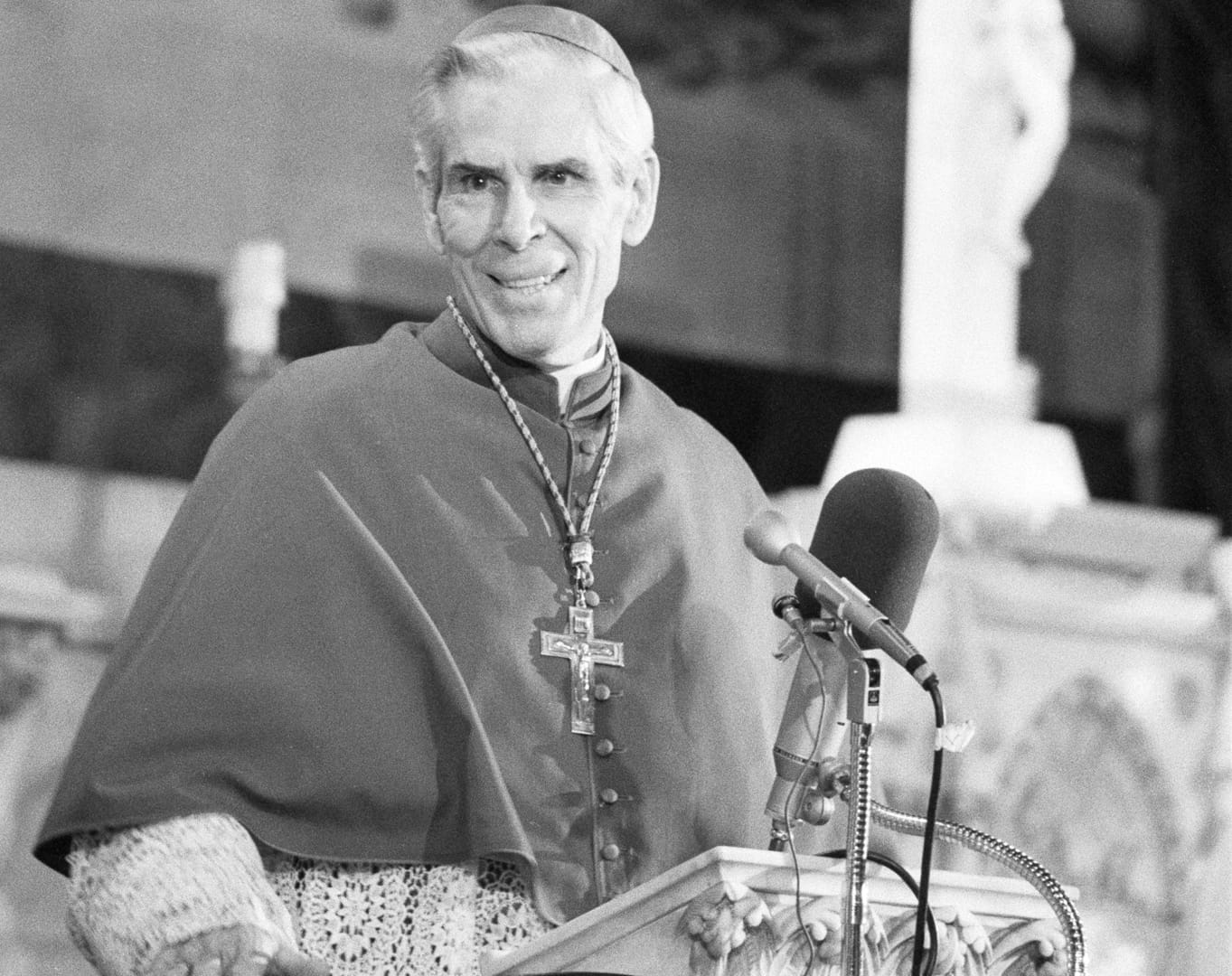

NEW YORK – Now that we know why the scheduled Dec. 21 beatification ceremony for the late Archbishop Fulton Sheen has been postponed, it raises broader questions about how we evaluate not only potential candidates for sainthood, but those who’ve already crossed the finish line, vis-à-vis the clerical sexual abuse scandals.

After being initially reported that the Vatican had postponed the beatification at the request of a “few U.S. bishops,” the Diocese of Rochester, where Sheen served as an auxiliary bishop from 1959 to 1966 and as the bishop until his retirement in 1969, acknowledged in a statement that it had requested the delay “to allow for further review of his role in priests’ assignments.”

To be clear, there’s no suggestion of any personal misconduct by Sheen. An official in Sheen’s home diocese of Peoria, Illinois, which spearheaded the beatification cause, told reporters the concerns focus on a particular Rochester priest accused of sexual misconduct during Sheen’s years as a bishop, but insisted that the case had been thoroughly investigated and no mishandling by Sheen was discovered.

The caution in Rochester is understandable, given that the diocese in September became the first in New York to seek bankruptcy protection amid a new wave of abuse lawsuits driven by a one-year window in the state to file claims previously barred by the statute of limitations. Some of those claims date back to the 1960s, and obviously the diocese doesn’t want the spectacle of watching a former bishop proclaimed a near-saint whose history all of a sudden could be a liability.

We’ll see how the review of Sheen’s record shakes out, but in itself the cesura illustrates a new fact of life about sainthood in the Catholic Church: Going forward, in order to claim a halo, any candidate who was in a leadership position in the Church – meaning, usually, a bishop or religious superior – will have to be shown to have had “clean hands” on the abuse scandals.

What that new standard leaves unaddressed, however, is what to do in the case of such a figure who’s already been proclaimed a saint, but whose record is later shown to have been suspect in terms of handling allegations.

Probably the best-known, and most delicate, for-instance is St. Pope John Paul II, who was beatified in 2011, just six years after his death, by Pope Benedict XVI, and canonized three years later in 2014 by Pope Francis.

At the time, some critics warned that an accelerated sainthood process risked embarrassment, depending on what a later review might unearth about the way abuse cases were handled on the late pope’s watch.

Back then, they mostly had in mind the late Mexican Father Marcial Maciel Degollado, founder of the Legion of Christ, who faced allegations as early as the mid-1990s but who didn’t face any sanction until after the transition to Benedict XVI, and who was clearly favored by high-ranking officials in John Paul’s papacy.

Today, one could easily add the case of ex-cardinal, and ex-priest, Theodore McCarrick. When (and if) the Vatican finally releases its long-awaited report on the contents of its archives related to McCarrick, it’s possible the record may suggest that certain officials close to John Paul had been made aware of concerns about McCarrick but, for one reason or another, did not react as aggressively as today’s standards would suggest.

In an Oct. 6, 2018, statement, the Vatican appeared to hint at such a possibility.

“The Holy See is conscious that, from the examination of the facts and the circumstances, it may emerge that choices were taken that would not be consonant with a contemporary approach to such issues,” it said.

Theologically speaking, once a pope canonizes a saint, the judgment is considered definitive, so no one’s halo is likely to be revoked. Further, sainthood has never been tantamount to a declaration of personal perfection, but more akin to a recognition that sanctity is achievable even amid flaws and failures.

The open question illustrated by the example of John Paul II – though hardly exclusive to him – is whether post-abuse crisis, the sainthood of certain figures now should come with an asterisk, much like the Hall of Fame status of baseball players who played during the steroids era.

Of course, there are legitimate defenses to be made of John Paul’s record. One could argue, for instance, that by the time either the Maciel or the McCarrick cases were coming to a head, the late pontiff was already diminished by age and disease and thus dependent on aides to handle such matters properly.

One could also make the argument that it’s unfair to project understandings and protocols that really solidified only post-2002 into the past – though, if that’s the case, then it’s hard to explain why it’s fair in the Sheen case either.

The larger point is that the clerical abuse scandals now provide a new prism through which saints, both prospective and already declared, will be seen.

Suppose, for instance, it should emerge that Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador, the martyred hero of the liberation theology movement, mishandled an abuse allegation against a priest? Suppose it turns out that St. Paul VI did the same while serving as the Archbishop of Milan? Suppose, indeed, we could somehow show that St. Charles Borromeo covered up an abuse charge, or St. Ignatius Loyola, or any other revered figure who once had responsibility over other clergy?

If the answers don’t seem intuitively obvious, that’s because they’re probably not – and that, in a nutshell, is what we might now be able to call the Catholic Church’s “Sheen dilemma.”