ROME – Recently the Catholic world has marked the death of two high-profile figures, Pope Benedict XVI and Australian Cardinal George Pell, each of whom leave behind a deep imprint on the history of their times.

Both are loved and revered by admirers, but because both held leadership positions, both had what would conventionally be described as a conservative agenda, and both were associated with the clerical abuse scandals, they were also highly controversial. Commentary about both deaths has generated considerable sound and fury, much of it laudatory and, equally, much of it bitterly critical.

As the same time, there have been two other Catholic losses of late, neither one of which has had much echo outside their own home towns.

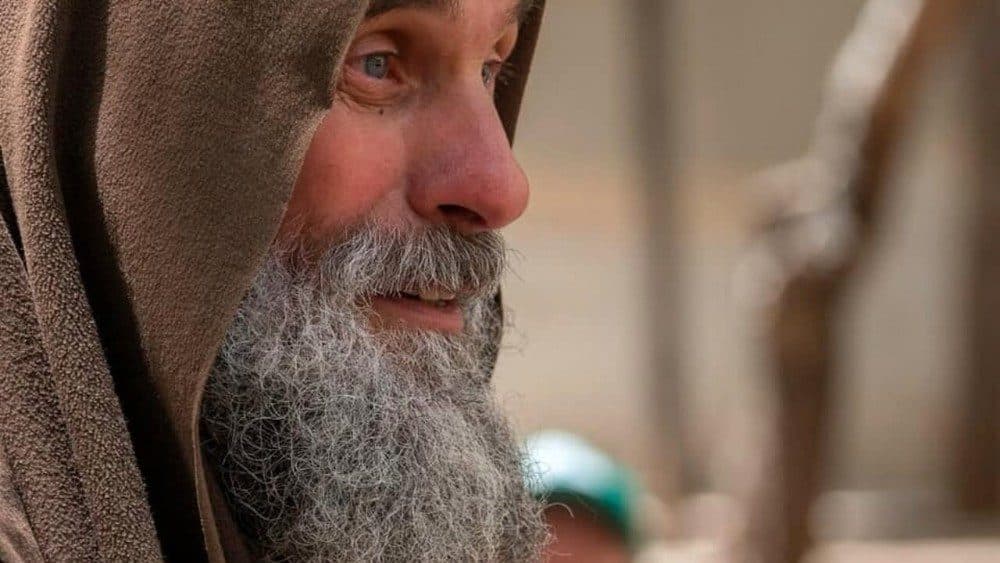

On Jan. 12, a Catholic layman named Biagio Conte, better known as “Fratel Biagio,” died in his native Palermo in Sicily at the age of 59, after a long battle against colon cancer.

The son of an upper middle class family, Biagio attended private schools and entered the family construction business until he was seized by a profound spiritual crisis in 1990. At first he went off into the mountains to live like a hermit, then set off on foot for a pilgrimage from Palermo to Assisi, a distance of almost 700 miles, in search of inspiration from St. Francis.

Having lost touch and fearing the worst, at one point his family went on an Italian missing persons TV program called Chi l’ha visto? to appeal for news, compelling Biagio to go on the show live to apologize.

Upon his return to Palermo, he began begging around the central train station to raise funds to care for the homeless persons who congregate there. Out of those efforts developed the “Mission of Hope and Charity,” a sprawling outreach ministry which today embraces three separate facilities in Palermo, collectively serving around 800 persons and 2,400 meals every day, as well as offering shelter, hot showers and basic medical care.

When Pope Francis visited Palermo in 2018, he had lunch at one of the mission’s centers, spending time with the homeless who ate there and with Conte.

While Conte never sought political or ecclesiastical power, he was adept at holding the powerful to account. More than once he organized protests, including his own lengthy hunger strikes, to demand that city officials step up their efforts on behalf of the poor.

For years, Conte was forced to use a wheelchair to get around Palermo because of crippling pain in his legs. In 2014 he traveled to the famed healing shrine of Lourdes and, after immersing himself in its waters, regained the ability to walk. The Archdiocese of Palermo would later declare that doctors “were unable to furnish a scientifically plausible explanation” for his recovery, effectively declaring it a miracle.

“While everyone else in his generation was shouting ‘God is dead,’ he turned his gaze to heaven to see God, that merciful and compassionate God who, in the end, he found in the poor, in migrants, in those who’ve lost everything, including hope,” an admirer once said of Conte.

“He walked, he rejoiced, he sang, he suffered, like St. Francis, who showed him the way.”

Also on Jan. 12, Sister Aderita Guidolin of the Franciscan Elizabethan Sisters of Padua, Italy, better known to everyone as “Sister Rita,” passed away at the age of 109. At the time she was the oldest consecrated religious person, male or female, in Italy, and a full 50 years older than Conte, who died the same day.

Born in 1913, Guidolin took her religious vows at the age of 21 and spent the next couple of decades as a cook and a helper in an after-school program for children in her native province of Padua.

She then went overseas as a missionary, first in Egypt (where she taught hairdressing and sewing at a school for female domestics) and then in Lebanon, learning to speak Arabic along the way.

Eventually declining health forced her to return to Italy, where she resumed her activity as a cook and aide in after-school programs run by her order. When she theoretically retired in 1996 at the age of 83, she moved into an assisted living facility but continued to be highly active, including volunteering at residences for poor families.

Once asked about the secret of her long life, Guidolin said, “I pray every day. Find time to do it, and you’ll live long and happy.”

The mayor of her native Padua paid tribute: “She led a humble, simple and hard-working life of service to her religious community and to society, even abroad, and she was an example of generosity for future generations.”

To be clear, the deaths of Conte and Guidolin won’t make international headlines. A week from now, no one outside either Palermo or Padua probably will even remember they happened.

Yet for precisely that reason, they’re more akin to the rule than the exception. Most Catholics will never be popes or cardinals. They will never hold the reins of ecclesiastical power, they won’t write books or give speeches that will echo through the ages, and they’ll never know real celebrity.

Yet, like Conte and Guidolin, countless scores of Catholics, inspired by the faith, will live and die trying their best to serve God and others. They may not go to the heroic lengths of a Conte, and they may not keep at it quite as long as a Guidolin, but in their own unspectacular way they’ll try to walk the same path.

In that sense, perhaps the comparatively quiet deaths of Conte and Guidolin are actually the key to a deafening Catholic story, which is the informal, and wildly diverse, “mission of hope and charity” which untold legions of believers carry forward every day, far away from the public narrative about Catholicism, but arguably forming the beating heart of the faith.