ROME – At the end of the 2007 movie “Charley Wilson’s War,” about how covert American support for the mujahadeen in Afghanistan helped bring down the Soviet empire, a quote appears from the real Texas congressman played in the film by Tom Hanks: “All these things happened, and they were glorious and they changed the world.”

“Then, we …”

Well, I can’t actually quote what Wilson said at that point, because this is a family news outlet. Suffice it to say, his point was that the people in charge didn’t handle the aftermath very well.

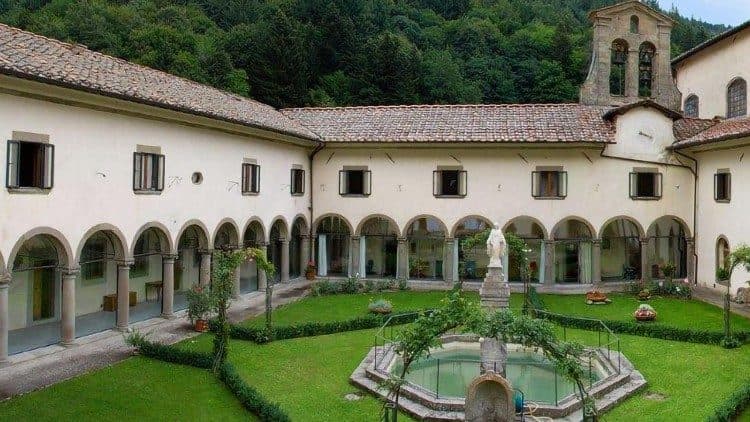

If a movie is ever made about the famed Italian Codice di Camaldoli (“Code of Camaldoli”), a blueprint for a just society produced by a cross-section of Catholic intellectuals and activists in July 1943 at a Benedictine monastery in Tuscany, that Wilson quote easily could serve as its denouement too … though, perhaps, not quite its final word.

Among the participants in that fabled summit eighty years ago this month were two future Prime Ministers of Italy, Aldo Moro and Giulio Andreotti; the future Mayor of Florence, Giorgio La Pira; and a future Cardinal of the Catholic Church, Pietro Pavan, who would go on to ghostwrite the social encyclicals Mater et Magistra and Pacem in Terris for Pope John XXIII.

The work was coordinated by Italian economist and intellectual Sergio Paronetto, a leader in the Catholic Action movement and a close friend and advisor to both Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, who would become St. Pope Paul VI, and Alcide de Gasperri, who would serve as Italy’s Prime Minister from 1946 to 1953, and who would also become one of the founders of the European Union and a candidate for sainthood himself.

It’s almost impossible to overstate the centrality of Catholicism for this cohort.

Andreotti, who would serve as Prime Minister in seven different governments, first met de Gasperri when both were young activists in FUCI (the “Italian Catholic University Federation,” basically the youth arm of Catholic Action) and they were studying together in the Vatican Library. When a prominent journalist later would say the difference was that when de Gasperri went to church, he talked to God, while Andreotti spoke to the priests, Andreotti shot back: “Priests vote, God doesn’t.”

Organized in seven sections and 99 individual propositions, the Codice di Camaldoli would become a key source for Italy’s post-war constitution and also serve as inspiration for the political platform of the Christian Democratic party, which governed the country for the next 50 years.

The backdrop to the gathering at Camaldoli was the stuff of high drama. Just eight days before the group assembled, American forces had launched the invasion of Sicily; the day after the meeting began, American bombers strafed Rome, dropping more than 1,000 tons of explosives and killing 3,000 people.

One day after the Camaldoli meeting concluded, Mussolini was ousted by the Grand Council of Fascism and placed under arrest, which would lead to the German occupation of northern and central Italy by September.

As a result, it was clear to the thinkers in Camaldoli that the old order was crumbling, and that something new would have to be built. It was, to some extent, an Italian analog to the U.S. constitutional convention in 1787, in that participants weren’t just considering reforms to an existing system but trying to imagine a new government from the ground up.

One key difference is that unlike what happened in Philadelphia more than two centuries ago, these Italian founding fathers were all Catholic and self-consciously trying to imagine a state rooted in Catholic social doctrine. To extend the analogy, the Codice di Camaldoli is akin to the American “Federalist Papers,” in that it reveals the aspirations of the architects of the novus ordo seclorum.

In terms of content, the Codice di Camaldoli identified two core pillars of a just society: The “common good,” and “social harmony.”

Beyond that, it listed eight principles which should govern economic activity (listed below in my translation from Italian).

- The dignity of the human person, which requires a well-ordered freedom of the individual also in the economic field.

- Equality of personal rights, notwithstanding deep individual differences as a result of different degrees of intelligence, ability, physical strength, etc.

- Solidarity, that is, the duty of collaboration also in the economic arena to reach the common goals of society.

- The primary destination of material goods for the advantage of all people.

- The possibility of ownership in various legitimate ways, among which work is preeminent.

- Free commerce of goods with respect for commutative justice.

- Respect for the exigencies of commutative justice in payment for work.

- Respect for the exigencies of distributive and legal justice in the interventions of the state.

One of its best-known prescriptions is this: “A good economic system must avoid excessive enrichment which damages equitable distribution. In any case, it must prevent the excessive power of small groups over the economy through the control of a few [individuals] over concentrations of wealth.”

In effect, the Codice di Camaldoli was an attempt to answer one of the most fascinating thought exercises in Catholic intellectual life of the last 150 years: What would an actual, real-world government based on papal social teaching since Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum in 1891 look like?

In some ways, the Codice was a rousing success.

Led by statesmen such as de Gasperri and the Christian Democratic coalition he founded, Italy negotiated the transition from fascism to democracy, constructed a social welfare state that aspires to guarantee a certain minimum dignity to citizens, held Communism at bay, and tried its best to balance growing secularization and religious pluralism with respect for the country’s traditional Catholic identity. In general terms, the Christian Democrats were also able to hold the political left and right together in a rough consensus.

On the other hand, we all know how the story ended: The Christian Democrats imploded in 1994 amid a series of corruption scandals known as Tangentopoli, or “Bribe City,” and many of the core principles of the Codice di Camaldoli were more honored in the breach than the observance. Despite the emphasis on a right to work, for example, Italy has long been plagued with one of the highest youth unemployment rates in Europe, especially in the chronically underdeveloped south, where talk of the “common good” and “social harmony” often seem little more than a cruel joke.

De Gasperri himself seemed to anticipate that the real-world application of the Codice would fall short of the ideal.

Here’s what he said at the time: “Approaching this session of Catholic Action is like climbing a great mountain. You find yourself in an oxygenated atmosphere. When you come down, it’s not always possible to maintain the same atmosphere … [one] has to seek a third way between the aspirations of principle and the possibilities of action.”

And, yet.

Despite it all, the Codice di Camaldoli remains arguably the most thoughtful, thorough and provocative effort in history to apply the principles of Catholic social doctrine to the hard work of real-world governance. The fact that it took shape in a famed monastery of the Benedictines, who have been in the business of sustaining and saving Western civilization for 1,500 years, probably isn’t an accident.

Perhaps the dream the Codice represents has never been fully realized … but that, by no means, suggests the dream is dead.

Follow John L. Allen Jr. on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr