VALLECORSA, Italy – On the church’s liturgical calendar, last Thursday marked the feast of the Assumption. For Italians, however, it was also Ferragosto, the annual summer holiday when cities empty out for days on end, beach resorts and mountain destinations swell with revelers, and work comes to a grinding halt.

The term is a contraction of the Latin phrase Feriae Augusti, the holidays of the Emperor Augustus, reflecting the fact that the mid-August break reaches back all the way to antiquity.

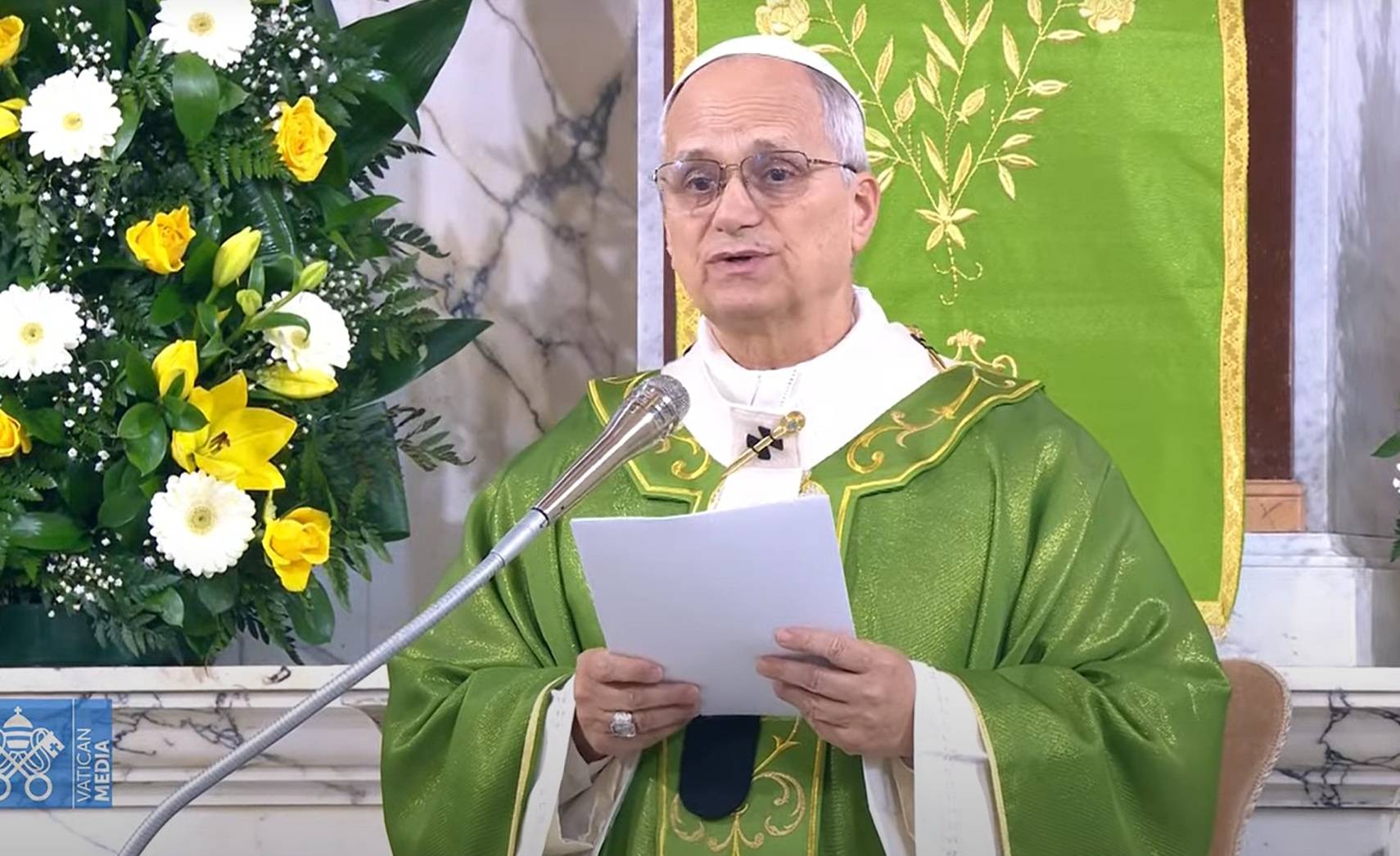

While technically the Vatican remains operational – Pope Francis takes his annual “staycation” in July, resuming his usual schedule in August – many personnel, especially Italian laity with families, are out of the office, and the place generally has a fairly sleepy feel.

That doesn’t mean, however, the Catholic church itself goes off the clock. Away from the spotlight – because, let’s face it, most reporters here are away during August too – ecclesiastical life grinds on, often enough generating some classic “only in Italy” moments.

This year, three vignettes in particular capture the unique fashion in which Catholicism is woven into the warp and whoof of Italian life, generating ironies and epiphanies that could only occur in il bel paese.

Colonial amends

Italy is home to scores of different women’s religious communities and societies, in part because once upon a time, founding an order of nuns was part of how an Italian bishop made his bones. Most of these groups are relatively small – according to statistics from the bishops’ conference, the average convent in Italy has eight sisters – and carry out their quiet missions far from the madding crowd.

Thus it was a bit unusual this week when the Suore della Divina Provvidenza per l’Infanzia Abbandonata (“Sisters of Divine Providence for Abandoned Children”), a community of fewer than 100 nuns founded in Piacenza in 1921, made national headlines for the election of a new Mother General.

The choice fell upon Sister Tigist Ashebir, an Ethiopian, who takes over from Italian Sister Albina Dal Passo, now 83, who entered the community in 1957 and who’s led the order since 2018.

In itself, the transition is hardly unusual. On the contrary, it’s the Catholic mega-story of our times: All over the world, young and dynamic churches in the developing world are taking the reins from the aging and diminishing West.

What captured the Italian imagination about this particular passing of the baton, however, is that it amounts to a small bit of justice regarding one of the darkest chapters of the country’s recent history, which was the colonization of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 under fascist ruler Benito Mussolini.

Though Ethiopia, in tandem with Somalia and Libya, was basically Italy’s only colonial enterprise, it was especially brutal. Among other things, Italian forces used mustard gas on both combatants and civilians, and even attacked hospitals and the Red Cross in order to discourage resistance. Hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians are believed to have died at Italian hands, including an estimated 20,000 in one three-day massacre alone in the capital of Addis Ababa in 1937, which was twenty percent of the city’s population at the time.

During the fascist era, Italian rule in Ethiopia was celebrated as a great conquest. The Roman neighborhood where my wife and I live, which had been known as Della Vittoria after Italy switched sides and joined the winning team in World War I, was rechristened as Delle Vittorie, plural, to include Ethiopia.

After the post-war transition to democracy, the savage rule of Ethiopia began to look less like a victory and more like a stain on the national conscience. Ever since, Italy has been trying to make amends: Our neighborhood, for instance, went back to calling itself Della Vittoria, hoping to shed the sense of shame that hung around its previous designation.

Thus for many Italians, the fact that an Ethiopian is now in charge of a religious order founded in Italy is a belated, admittedly small and inadequate, but still meaningful nod to making past wrongs right.

Of tomatoes and titles

Though Italy didn’t give birth to the tomato – that honor belongs to the Andes region of Peru and Ecuador – arguably no place loves it more. Italians lead the world in per capita consumption of tomatoes, with the average Italian consuming a staggering total of 220 pounds a year.

The San Marzano variety of tomato, grown largely in the southern region of the country between Naples and Sorento, is widely considered perhaps the world’s finest, and is a source of intense national pride.

Yet what’s less known is that the field hands who cultivate Italy’s tomatoes, as well as the factory workers who process them, often work under intense pressure during harvest season, facing long hours, low pay, and frequent workplace accidents. Attention to their fate has risen lately amid a general spike in concern about worker safety in the country; recently one of Italy’s major unions placed almost 200 coffins in front of Milan’s famed La Scala Theatre to represent the more than 1,000 workers who died on the job last year.

All that makes a recent gesture of Father Gerardo Coppola, a young priest and pastor the Church of St. Anthony of Padua in the southern Italian town of Pagani, especially touching.

Coppola made his way to one of the massive tomato canning factories that dominate the lands just outside his city of roughly 35,000 people this past week, with the intention of offering a blessing and expression of solidarity with the largely female workforce. He showed up outside at noon, knowing that a shift change would be underway so he could catch both those exiting the factory and those coming on to work.

Coppola was invited inside the factory and made the rounds, offering personal blessings, delivering hugs and prayers, and taking selfies with the workers.

“In our area, the tomato processing industry is a huge and strong presence,” Coppola said. “There are lots of seasonal workers who, while everybody else is on vacation, come here for work to supplement their family income or to pay off some debts. They’re a richness for us.”

What lifted this story to national attention is an amusing irony: In Italy, priests are known as “Don,” a contraction of the Latin dominus, so Coppola is known to basically everybody as “Don Gerardo.” As it happens, one of the largest and best-known processing plants in the area is run by the Feger company, whose best-known brand of canned peeled tomatoes is called … wait for it .. “Don Gerardo.”

The line is named for the company’s founder, layman Gerardo Ferraioli, who was informally afforded to honorific “Don” in recognition of his entrepreneurial acumen.

Nonetheless, the fact that another “Don Gerardo” came to bless workers who can the tomatoes bearing the same name couldn’t help but seem to many Italians absolutely charming. (For an American analogue, imagine a war hero named Colonel Sanders visiting the headquarters of Kentucky Fried Chicken, and you’ll get the idea.)

Church and Rome

One enterprise that definitely doesn’t take a break for Ferragosto is soccer’s transfer window, known in Italian as the calciomercato, or “soccer market.” Every club in the country is scrambling to fill out its roster, trying to add as much talent as possible before the window closes at the end of the month.

One player who’s been very much at the center of attention is Federico Chiesa, a 26-year-old striker who’s played the last four seasons for the perennial Italian powerhouse Juventus. He became a national hero in 2021 for his star turn during Italy’s run towards the European soccer championship, which culminated with a victory over England at Wembley Stadium.

The management of Juventus, however, has made it clear that Chiesa no longer fits into their plans, and they’re looking to make a deal. He’s been variously rumored to be destined for other Italian clubs, for European squads such as Chelsea in England’s Premier League, and, inevitably, for a couple of deep-pocketed teams in Saudi Arabia.

As part of the sea of speculation, there’s also been talk that Roma, one of two top-flight Italian clubs in the city of Rome – the other being Lazio, named for the surrounding region – might be among the possible landing places.

On that front, one well-known soccer writer for a major Italian publication, which is more or less the Sports Illustrated of Italy, recently published an essay arguing that Chiesa’s particular skills set wouldn’t be a good fit for the tactical approach of Roma’s new coach, former player Daniele De Rossi.

To be clear, “chiesa” in Italian is also the word for “church,” while “Roma” is not just the soccer team but also the name of the city.

Herewith, then, the immortal headline of our sportswriter’s piece: Per la salute di Chiesa, deve stare lontano da Roma, which, if you put it through a translation app, might well give you, “For the church’s health, it needs to stay aaaaway from Rome.”

That’s got to be one of the great journalistic double entendre of recent memory, and it’s obviously intentional. Once again: Only in Italy, folks, only in Italy.