ROME – While Pope Francis has written once again to cardinals to warn them of financial difficulties at the Vatican, this time focusing on a “serious imbalance” in the pension fund, his own workforce is raising alarms about a different sort of shortfall – a “trust deficit” about the scope of the problem and how to fix it.

It’s been the Vatican’s worst-kept secret for some time that the pension system is in trouble. In 2020, for instance, the late Cardinal George Pell, former head of the Secretariat for the Economy, sounded an alarm that the Vatican is “slowly going broke,” citing a ballooning deficit in the pension fund. In 2022, that deficit was estimated at around $664 million just for the Holy See, rising to $1.04 billion if one includes the Vatican City State and the Vicariate of Rome.

Thus when Francis wrote the cardinals of the world on Nov. 19 to report that current pension management “generates a significant deficit,” and that analysis shows this “imbalance” is increasing over time, it really didn’t come as a shock to anyone.

“In real terms, the current system is not able to guarantee in the medium term the fulfilment of the pension obligation for future generations,” the pontiff wrote, saying “urgent structural measures, which can no longer be postponed,” are required, which will require “generosity and willingness to sacrifice on the part of all.”

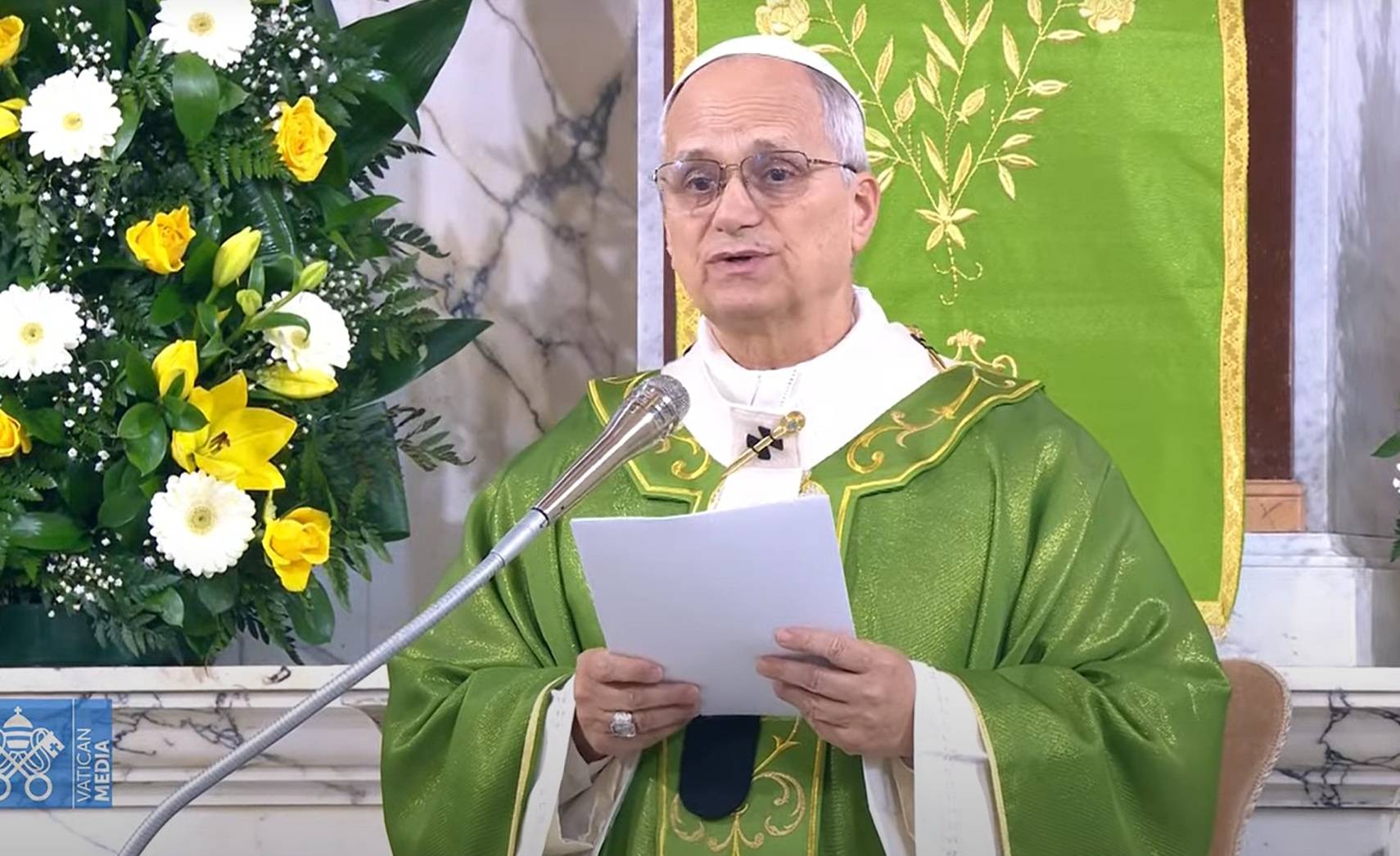

He also named American Cardinal Kevin Farrell as the sole administrator of the pension fund. Over the years, Farrell has emerged as the pope’s financial “Mr. Fix-It”: In addition to serving as Prefect of the Dicastery for Laity, Family and Life, Farrell is also the Camerlengo, a position which oversees properties and revenue of the Holy See, and he becomes acting sovereign upon the death or resignation of the pope; he’s president of the Reserved Materials Commission, which oversees sensitive contracts; and he’s president of the Committee for Investments, which oversees the Vatican’s investment portfolio.

On the surface, all that seems to demonstrate awareness of the problem and a determination to fix it. Yet Vatican employees this week declared the Italian equivalent of, “Not so fast!”

In a Nov. 21 statement, two days after the pope’s letter, the Association of Lay Vatican Employees (Adlv), the closest thing the Vatican has to a labor union, ticked off several reservations about the call for “sacrifice on the part of all.”

First, they objected that they’ve never seen the pension fund’s balance sheet, which sows doubt about what’s really happening.

“When you contribute to pension management, as we pay with our contributions, the accounts should be available to everyone,” the association said. “In the Vatican, however, this information is available only to a few.”

“We should understand how the deductions from employees’ paychecks are administered,” the Advl statement said.

Second, the association noted, Vatican employees have already “tightened their belts” in many ways. For one thing, they noted that a suspension of automatic biennial pay increases from 2021 to 2023 will cost employees as much as $20,800 over the course of their careers. Moreover, employee salaries are not indexed to inflation, but the rents they pay on Vatican-owned apartments are.

Third, the association said that despite handwringing about deficits and calls for cutting back in recent years, this has not stopped the Vatican from contracting with expensive external consultants or from taking on new management-level personnel as exceptions to a general hiring freeze.

“If we now want to intervene on pensions, then what results has the financial reform launched four years ago had?” the Adlv statement asked. “What results have been brought by the ad hoc staff hired, often with considerable salaries?”

Fourth, the association wondered aloud if the Vatican’s Secretariat for the Economy has considered methods for boosting income, or possibilities for reductions in other areas that would not require further cuts in employee salaries, “already reduced to the minimum.”

There’s a special irony, the association noted, in imposing such hardships on working parents while the pope repeatedly makes public appeals for the protection of families and meeting their needs.

Fifth and most basically, the association complained that its repeated requests to be able to talk all over with Vatican managers have been ignored.

“Employees, exhausted by cuts and above all by the lack of answers to their legitimate requests to be heard, including through the Adlv, believe they have already contributed, to the maximum of their possibilities, to replenishing the deficit, and vigilantly await any future provisions.”

“We hope that the Adlv will be received soon to discuss all these issues,” it said.

The irony that the Vatican just wrapped up a three-year synod process on synodality, which cost God knows how much money and which was premised on building a more participatory and consultative Church, while the group representing its own employees – including, for instance, the people who set up the round tables for synod sessions, brewed the coffee for its breaks and photocopied its vast paperwork – can’t even get a meeting is, well … fairly thick, to say the least.

The Association of Lay Vatican Employee was created in 1982, and formally recognized by the Holy See in 1993. It enjoys observer status with the International Trade Union Confederation. Its current president, Paola Monaco, is a 20-year veteran of Vatican service, and certainly knows her way around financial matters, having spent most of that time in what once was the Prefecture for Economic Affairs and later with the Council for the Economy.

At the moment, there are more than 700 formal members of the Adlv, out of a total workforce of about 4,000, and requests for membership are said to be growing.

What all this suggests is that if Pope Francis and Farrell want to fix the pension deficit, they might need first to address a trust deficit in their own house – if, that is, they genuinely expect “willingness to sacrifice on the part of all.”