When Pope Francis’s “C-9” council of cardinal advisers got together last month, among the topics of discussion were two new super-departments in the Vatican the council has recommended and which Francis has decided to create: One for “Charity, Justice and Peace,” and another for “Laity, Family and Life.”

Rome being Rome, a hot topic of conversation around town since talk of the new departments first surfaced has been, “Who’s in line to run these outfits?” The presumption is that either position is fairly desirable, since it means heading a department with considerable personnel, authority and visibility. Though it isn’t written down anyplace, the assumption is also that if whoever is tapped isn’t already a cardinal, he’ll be made one as a condition of the new post.

From the outside, it may seem that any Catholic cleric in his right mind would want the job.

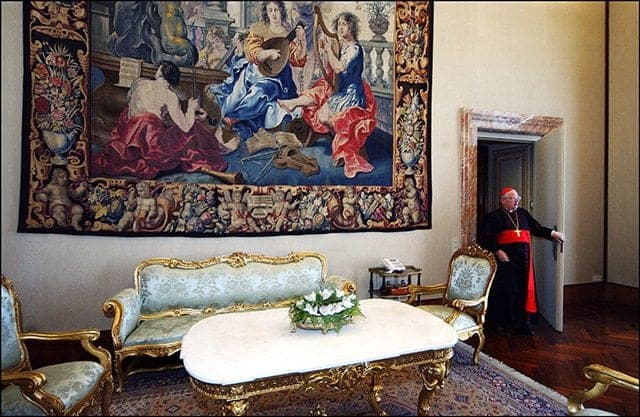

When you’re fairly far up the ladder, like an archbishop or cardinal, a Vatican gig is undeniably a pretty sweet deal: You get a healthy monthly stipend, generally a great apartment in prime Roman real estate, the best tables at all the restaurants in town, and you’re treated like a celebrity everywhere you go.

In addition, the prime directive in bureaucracies everywhere is to move up, and common sense would say that in the Catholic Church, the Vatican is a step up from, say, a parish, or a seminary, or a local diocese.

Yet one of the names making the rounds right now is someone I know who’s currently running a diocese, so I reached out to ask what he’s hearing. The gist was that he hasn’t heard anything, and, while he obviously will do whatever the Holy Father asks, based on his own preferences, he’d run screaming into the night before taking such a position.

That may seem like deflection, but knowing this person, I can vouch that his reluctance is utterly real.

In truth, there are at least five good reasons why a Catholic priest or bishop might not recoil from a Vatican position, quite apart from a pietistic sense of personal unworthiness.

(By the way, I meant what I said above – the vast majority of clergy would do whatever the pope asks, regardless of their personal desires, but it’s those desires I’m talking about.)

First, there’s a question of personality. Some people instinctively regard living in another culture and learning another language as romantic, whereas others would be homesick from the moment they leave until they’re finally cut loose.

Second, many Catholic leaders are convinced that for reasons both theological and pastoral, the real action in the Church is at the local level. Yes, the Vatican is critically important in terms of setting policy and answering questions about the faith, but all of that, they think, is secondary to the real drama of individual people’s spiritual lives.

In the end, the faith either comes alive or it doesn’t at the local level, and so they believe that their greatest contribution can be there.

Related to that, some bishops also feel they have a much better opportunity to help shape their national conversation from a diocese inside the country than they would sitting in an office in Rome. As a Vatican official, often the only national conversation you have a chance to effect on a regular basis is Italy’s, and even that’s hit and miss.

Third, everyone knows that promoveatur ut amoveatur is a time-honored principle in the Catholic Church, roughly meaning “to promote in order to remove.” The idea is that sometimes the face-saving way to get rid of someone is to promote them to a theoretically higher, but in reality less consequential, position.

As a result, the natural gut reaction some Catholic heavyweights have when news breaks they’re under consideration for a Vatican gig is, “Who wants me gone?”

Fourth, most Catholic clergy learned a long time ago to distinguish between the teaching authority of the papacy and the institutional infrastructure of the Vatican, and they don’t typically see the latter through rose-colored glasses.

Often, they look at the Vatican and see yet another bureaucracy, subject to the same dysfunction, corruption, and occasional pointlessness as all the rest, and they don’t regard spending a chunk of their lives in that environment as an especially attractive option.

Fifth, let’s face it: In his own diocese, virtually every Catholic bishop in the world is the star of the ecclesiastical show. He’s the commander-in-chief, the top teacher of the faith, the ultimate financial decision-maker, and so on.

In the Vatican, heads of departments are important, but no one would confuse them with the place’s main draw. Especially if they run a major diocese, many bishops actually would see a Vatican appointment – depending, in part, on where they’re headed – as a demotion.

All of which illustrates the challenge facing Francis, like any pope, in finding the right people for the posts he has to fill. It’s not just a question of subject-matter competence, but who’s in a position personally and emotionally to give it their best.

That’s a special problem, perhaps, in Catholicism, where it sometimes can be tough for a pope to get an honest answer. If the question is, “Will you accept the Holy Father’s request?”, almost anybody raised in the clerical system is trained to say simply, “Yes.”

(By the way, not wanting a job is hardly disqualifying in terms of being suited for it. There are plenty of people capable of summoning their best efforts despite their personal feelings, and the fact that someone isn’t lusting after a position may well be a mark in their favor.)

Fortunately, Francis, who didn’t especially want to relocate to Rome himself, is probably in a better position to evaluate given cases better than most.

As part of that picture, he knows in his bones that popular mythology aside, it’s just not the case that every cleric in the system secretly yearns for the chance to get saluted by Swiss Guards every day on their way to work.