ROME—Now that the dust has settled a bit on Pope Francis’s Jubilee Year of Mercy, which formally ended last Sunday, it’s worth looking back at some of its key moments, trying to gauge how the pontiff’s appeal for a more merciful world resonated within the Church and beyond.

The photo album

It’s often said that pictures are worth a thousand words, and with few modern-day leaders is this as true as it is with Francis.

If he were a politician on the campaign trail instead of the spiritual head of 1.2 billion Catholics around the world, several pictures taken during the last year could have been perceived as a photo-op.

Yet they were intended as strong appeals for mercy, both the mercy dispensed by God and also that which is due one’s neighbors.

Opening the Holy Door in the cathedral of Bangui

Although the Holy Year was officially launched in Rome on December 8, Francis opened the first Holy Door a week earlier, during his visit to the Central African Republic, where violence between rival Christian and Muslim militias has left at least 6,000 people dead.

This was the first holy door ever to be opened outside of Rome.

“The Holy Year of Mercy came early to this land, a land that for many years has been suffering,” the pope said. “All the suffering countries in the world that are going through the cross of war are also represented in this land.”

Francis’s visit to the Central African Republic was an especially apt setting for that message of mercy, bringing the pope to one of the world’s poorest nations and also representing the first time that a modern-day pontiff set foot in an active war zone.

“All of us ask [God] for mercy, reconciliation, forgiveness and love,” Francis said, before pushing open the doors of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, using two hands to get the job done.

Over 10,000 more holy doors were opened throughout the world, because the pope’s goal was for the Jubilee Year to be celebrated locally, not just in Rome. According to the pope’s document Misericordiae Vultus, calling for the Holy Year, particular churches had to open their own doors as a visible sign of the Church’s universal communion.

Hence there were holy doors opened in a modest tent at a refugee center in Erbil, Iraq, in China where the faithful called the fact that not one of the 10,000 pilgrims who gathered for the opening last December was arrested a “miracle,” and in prison chapels.

In the Italian regions hit by a series of earthquakes last August, local bishops put up makeshift “holy doors” in the tent camps that sprung up to house people who had been displaced.

Opening the Jubilee Year of Mercy with his predecessor

From the beginning of Francis’s pontificate, in some quarters the narrative has been that he’s the opposite of emeritus Pope Benedict XVI and that the two are at odds with each other. Never mind the fact they’ve publicly praised each other several times, and the pictures of their many encounters show nothing but open and honest smiles.

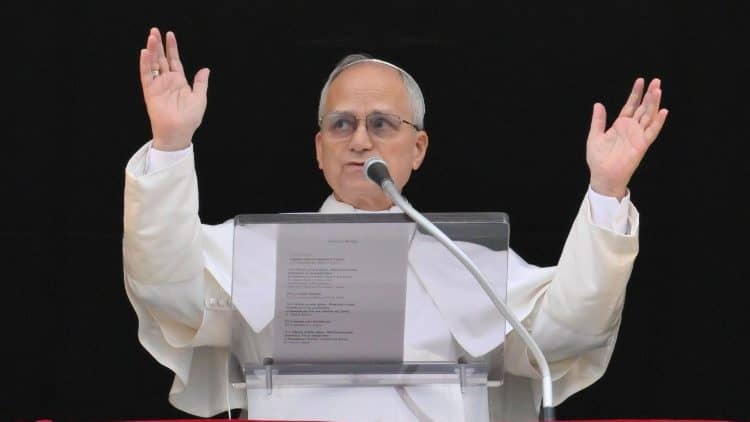

So the pope’s decision to invite his predecessor to be present at the opening of the Jubilee, where Francis broke all protocols to embrace the man he’s called “revolutionary” before leading the solemn ceremony shouldn’t have been a surprise to anyone paying attention. Benedict was the second pilgrim to go through the holy door at St. Peter’s Basilica. Once inside, the two embraced again.

On that day, Francis said that the jubilee was to be a year in which Catholics were called to grow ever more convinced of God’s mercy, which should always come before judgment.

“How much wrong we do to God and his grace when we speak of sins being punished by his judgment before we speak of their being forgiven by his mercy,” he said as he celebrated a Mass in St. Peter’s Square.

“We have to put mercy before judgment,” he added.

The Friday’s of Mercy initiatives

Mostly in Rome, but not exclusively, once a month on Fridays, the pope made a point to live one of the “works of mercy” the Catholic Church teaches about, trying to urge the faithful- and the hierarchy- to follow suit.

Among other things, he visited a house for the elderly and one for the terminally ill, a community for recovering drug-addicts, refugees and migrants stranded in the Greek island of Lesbos, a center for people with serious intellectual disabilities, and a home for elderly priests.

In July, he went to the concentration and extermination camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau during his visit to Poland for World Youth Day, and on the following months he visited a center for women rescued from slavery, the ward for premature-born babies at a Roman hospital, a children’s hospice and a group of men who left the priesthood to form a family.

All of these visits had a strong pastoral meaning, but at least in some cases, there was more to the pictures of each event than Francis’s intention to accompany these people in their suffering.

For instance, in a recent interview with Italian network TV2000, the pope himself spoke about two moments that moved him: meeting women rescued from a situation of modern day slavery, including forced prostitution, and a hospital ward for premature babies.

When telling the story of the first, Francis said he hadn’t been able to avoid thinking about “the men who paid the girls: Don’t they know that with that money, to have some sexual satisfaction, they helped the exploiters?”

He wasn’t just bringing comfort to the women who needed it, he was making an international appeal to end human trafficking, the world’s third most profitable illegal industry.

When visiting the hospital, the pontiff was particularly touched by the tears of an inconsolable woman who’d given birth to three babies, one of whom hadn’t survived.

On that occasion, the pope didn’t just visit the sick, he was also making a strong appeal to end the “horrendous crime” and “very grave sin” of abortion.

Similar parallels can be drawn by his visit to the terminally ill and the Church’s stance against euthanasia, Auschwitz-Birkenau and persecution of people for ethnic and religious reasons, and so on.

The Jubilees for prisoners and for the homeless

There were several “major events” celebrated in Rome throughout the year, such as the canonization of Mother Teresa, the Marian Jubilee, the Jubilee for children, which saw 100,000 kids coming to Rome, one for the sick and disabled, and the jubilees for priests and deacons.

But on the last two weekends before the closing of the Holy Year, the attention was focused on two groups that represent what Francis has often described as “the outskirts of society” and the “throw-away culture.”

On the weekend of November 4-6, over a thousand inmates from around the world, including about 50 from the United States, accompanied by family members and prison workers, traveled to Rome to participate in the jubilee for prisoners.

The event had a clear spiritual message, with Francis reminding those present that God’s mercy knows no jail bars. Yet it also had a political undertone, with the pontiff calling for improvements in the conditions of prisons so that “the human dignity of the detainees is fully respected.”

He also called for the “competent civil authorities” to consider granting clemency to detainees suitable for benefiting from such a provision, and he once again reiterated his invitation to end the death penalty.

A week later, thousands of homeless men and women from around Europe came to Rome, in what organizers hope will become an annual pilgrimage to the Eternal City.

Their jubilee, formally described as the one for Socially Excluded People, included an audience with Francis on Friday, prayer vigils around Rome that same day, participating in the monthly Saturday jubilee audience with the pope, titled “Mercy and Inclusion,” and a Sunday Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica, presided over by the pontiff.

“I apologize in the name of Christians who don’t read the Gospel finding poverty in the center,” he told them during the weekend.

“I ask for forgiveness for all the times that Christians in front of a poor person or in a situation of poverty, looked the other way. Forgive us. Your forgiveness towards men and women of the Church, who don’t want to look at you or didn’t want to look at you, is like holy water for us.”

The Jubilee way beyond the Tiber

Time and time again, Pope Francis called for the Year of Mercy to be lived not as a pilgrimage to Rome but as a local event, in churches, prisons, schools and hospitals.

He called for dioceses from around the world to think of specific “monuments of mercy” that could remain after the doors were closed as concrete signs of this jubilee. Francis made this appeal on April, as he was leading celebrations in Rome on Divine Mercy Sunday.

“As a reminder, a ‘monument’ let’s say, to this Year of Mercy, how beautiful it would be if in every diocese there were a structural work of mercy: a hospital, a home for the aged or abandoned children, a school where there isn’t one, a home for recovering drug addicts — so many things could be done,” he said at a prayer vigil on Saturday.

Leading by example, he decided to finance two said monuments: An Agricultural School in Burkina Faso and a new Cathedral in Moroto, Uganda.

Archbishop Leo Cushley of St. Andrews and Edinburgh, Scotland, decided to create an app for smartphones which uses GPS to let users know where the nearest churches are, with updated Mass schedule and the hours when the sacrament of Reconciliation is available.

In Faisalabad, Pakistan, Bishop Joseph Arshad is set on reopening the St. Dominic medical dispensary, which provided care for 12,000 people a month, but which had to be closed for lack of funds.

In Port Pirie, Australia, Bishop Gregory O’Kelley, sent a circular letter to every priest in his diocese in May, to be read at Mass, asking for Parishes, church agencies, schools, communities and families within the diocese to plant a tree or trees (or an avenue or a woodlot) as a Memorial of the Year of Mercy.

“The idea is to have community involvement and for it not to be left to the parish priest to ensure the survival of the tree for instance!” O’Kelley said in the letter.

In Poland, we4charity was a campaign launched around World Youth Day to finance a mobile clinic, sent to Lebanon. Organizers of the youth rally that gathered millions also built a house for the elderly next to the big campus where the closing vigil and Mass took place and also a Caritas distribution center, called “Bread of Mercy.”

In the diocese of Ranchi, India, the monument of mercy took the shape of a hospital for the poor and the tribals.

In the Americas, 15 cardinals, 120 bishops and laity from over 22 countries came together in Bogota, Colombia, last August, to celebrate the Extraordinary Jubilee as a united continent. It was organized by the Vatican’s commission for Latin America, the conference of Catholic bishops from Latin America and the Caribbean, and the bishops’ conferences of the United States and Canada.

But Francis also extended an invitation for non-Catholics to join in, something which Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, took to heart. The leader of the Church of England participated in the ceremony for the closing of the Holy Door at Westminster Cathedral, saying that the Year of Mercy has “caught the imagination” of all Christians.

Welby also described the frequent absence of mercy in everyday life.

“Whether it is in elections and referendums, or in the international politics of refugees, of trade and commerce, and even in our own lives and expressions through social media, mercy is often absent,” he said.

Noting that the Holy Year had taken place 50 years after the end of the Second Vatican Council, Welby said that that this year “has been received as water in the desert for global churches sadly lacking mercy, and must be offered as the way of living to a world which sees mercy only in terms of exchange, and never as the excess of abundant love.”

After the jubilee for prisoners, some governments answered to his appeal.

The Castro regime in Cuba, took note announcing soon after Francis’s appeal the release of 787 prisoners “in response to the call by Pope Francis to heads of state in the Holy Year of Mercy.”

The statement said that those pardoned include female, young and sick prisoners but not those who have committed “extremely dangerous” crimes such as murder or rape. Since the government denies having “political prisoners,” no comments in this regard were made.