ROME— There’s a natural tendency for people everywhere to forget that the pope is a global leader, and to assume that whatever he says or does is directed at them. Under Pope Francis, that may be a special temptation for Argentinians, because he’s one of them, and for Americans, because it’s where media discussion of the pope is often most animated.

More often than not, however, that sort of myopia is a mistake.

Recently, for example, Pope Francis talked about the “virus of polarization,” an “epidemic of animosity and violence,” and about the dangers of walls being built. Americans tended to hear references to their political climate and to the new administration of Donald Trump.

In reality, however, the pope’s horizons are almost certainly far broader.

Those walls

For many Americans, papal rhetoric about walls inevitably comes off as a reference to Trump and his immigration policies. Those who favor the wall say the pope is anti-American, and that he should mind his own business. Those who are against it see it as papal support of an anti-Trump crusade.

But here’s the thing: the pope has global responsibilities, and a wall along the United States-Mexico border is far from being the only, and some would argue most threatening, wall in the world today.

Francis has often been labeled as a pope of gestures. Arguably, few gestures he’s made have had more impact than his praying at the Israeli West Bank barrier in his visit to the Holy Land.

Then there’s the ironically named Korean Demilitarized Zone, dividing North and South Korea, which just happens to be the world’s most heavily militarized border.

Though less visually evident, there are also walls around several Syrian and Iraqi cities. Aleppo, once Syria’s second most important city, for instance, has virtually been under siege for six years now, with basic things such as food, medicine and electricity, not to mention peace, becoming rare commodities.

All across Europe, including among many Catholic countries, borders have been closed, to keep immigrants out, and many living and serving in the refugee welcoming centers have re-named the facilities detention centers.

Though admittedly an oversimplification, many have argued that the United Kingdom voted Yes on the Brexit referendum because they couldn’t build a wall to stop the influx of refugees fleeing war, hunger and persecution in Africa and the Middle East.

In other words, memo to Americans: Not every papal use of the word “wall” is directed at you.

Polarization

Again, based on the vitriol and division that this presidential election created in the United States, it’s hard not to think that when the pope talks polarization, he’s thinking solely about the Land of the Free.

It’s well known, for instance, that across the United States these days, some families are struggling to get people together for the Thanksgiving holidays because of disagreements over which candidate people supported.

Yet in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, people from one neighborhood don’t dare enter another because the city has been divided by different factions in an ongoing civil war that has its religious components.

In eastern Ukraine, Russians and Ukrainians are fighting what Sviatoslav Shevchuk, the head of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, has defined as the “forgotten war.”

In Nigeria, the Muslim terrorist group Boko Haram has caused almost 3,000 casualties this year alone, but the death toll is close to 30,000 people in less than a decade, plus 2.3 million displaced people.

According to the United Nations, the ongoing war in Afghanistan has killed 10,000 people in the last 11 months.

Even among Church watchers, it’s too easy to reduce the pope’s words to whatever the latest intra-Catholic dispute is.

This weekend, for instance, Francis’s homily in the consistory for the creation of new cardinals was taken by some as the pontiff putting down specific bishops-most of them Americans- who’ve engaged in public crossfires over his document on the family, Amoris Laetitia, or as a response to a small group of conservative cardinals that has floated the idea of a public “correction” of the pontiff.

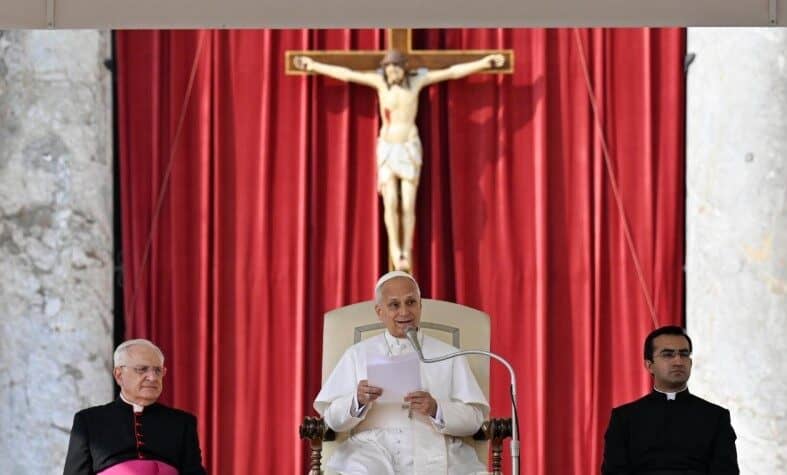

Granted, it wasn’t all that far-fetched: “How many situations of uncertainty and suffering are sown by this growing animosity between peoples, between us!” Francis told a St. Peter’s Basilica filled with cardinals and bishops from the four corners of the world. “Yes, between us, within our communities, our priests, our meetings.”

Yet animosity among bishops – or the laity, for that matter – did not begin this week, nor three years ago.

Some have been holding a grudge for decades and often seem a little too eager to let it all hang out.

Never mind that the fighting – which goes beyond passionate dialogue in the public sphere, giving way to name calling and public shaming – has an extremely negative impact in many Eastern European nations, where Catholic bishops are struggling with reviving a Church that was for too long oppressed by Communism.

For bishops, priests and laity in such contexts, it’s often difficult to make a persuasive case for unity when members of the Church to which they belong often seem bent on being at one another’s throats.

The “it wasn’t me” issues

Of course, there are also things Francis — exactly like his predecessors — speaks about, and absolutely no one seems to feel it’s directed at them.

“It makes no difference where arms come from; they circulate with brazen and virtually absolute freedom in many parts of the world,” the pontiff told the United Nations World Food Program this June. “As a result, wars are fed, not persons.”

The countries that signed the Paris agreement on climate change seemed all too happy to quote Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’, yet based on the international silence over arms trade, one would think weapons materialize in conflict zones out of thin air.

This could be an American issue since according to a 2015 study from Mexico’s governmental research service, an estimated 2,000 weapons are trafficked from the United States into its southern neighbor each day.

That means the United States imports 83 illegal weapons into Mexico each hour, 365 days a year.

One might argue the pope gives too many addresses in any given day, so perhaps someone missed his (repeated) denunciations against arms dealing- both legal and illegal. But Laudato Si’ for instance, wasn’t just a call for reducing carbon emissions.

It also had an intrinsically pro-life message, and a clear warning to those who see global warming as a justification to reducing the world’s (human) population. In rather blunt language, Francis said that concern for the protection of nature is simply “incompatible with the justification of abortion.”

Often accused of not being pro-life enough, he’s called abortion a “scourge,” a “great sin,” a “horrendous crime” and defined a just society as one that “recognizes the primacy of the right to life from conception to natural death.”

He’s compared abortion activists to the Italian Mafia, drawn a parallel between abortion and Herod’s slaughter of the innocents, and wondered aloud how “modern” societies can get up in arms over parents spanking their children when they have laws “allowing them to kill their children before they are born.”

Real abortion statistics in countries where this practice is illegal are hard to come by. But, in the United States, in the last 43 years, an estimated 60 million pregnancies have been terminated. That’s the equivalent to the total population of Francis’s Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and half of Chile.

The first pontiff of the Global South also time and time again has decried the fact that there are people dying of hunger around the world, and he’s not wrong.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, roughly one third of the food produced in the world for human consumption every year — approximately 1.3 billion tons — gets lost or wasted.

The United Nations’ World Food Program offers statistics on hunger: Some 795 million people in the world do not have enough food. That’s about one in nine people on earth.

Then there’s the blood-chilling statistic of children dying of hunger: Before Christmas gets here, 3.1 million girls and boys under five will have died because 1.3 billion tons of food are wasted every year.

Or, as Francis told the general assembly of the Catholic charity Caritas Internationalis in 2015, people are dying because “there is a lack of willingness to share.”

Then there are the statistics of those children who have died amidst bombings, and too many generations knowing nothing other than war.

Cherry-picking papal words

It might be a healthy exercise, whenever the spiritual leader of 1.2 billion Catholics speaks, neither to over-personalize nor over-generalize everything he says.

That also applies to the fact that the Church believes in the continuity of the papal magisterium, so the Successor of Peter doesn’t overrule what his predecessors have said.

When Francis is talking about divisions, he’s not just talking about the United States or Argentinians (who believe themselves to be so important as to take a Tweet from Francis’s nine accounts on the eve of Labor Day as a direct reference to a general strike against President Mauricio Macri).

He has Syria, Iraq, the Central African Republic, Nigeria, Ukraine, Russia, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Venezuela, Colombia, the Koreas, Mexico, Pakistan, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya and Iran in mind too, and other places beyond.

And when he talks divisions in the Church, he doesn’t mean between priests, nuns and bishops, but among the faithful too.

Then again, when Francis speaks about labeling “those among us with the status of a stranger,” even “an enemy” because they’re immigrants or refugees, or because they have different religions, customs, skin color, language or social class, as he did Saturday, he’s not (only) talking about Syria, the Central African Republic or Timbuktu.

He’s also talking about the United States.

Statistics from a 2011 study from the Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health (i.e. before the 2016 presidential race) show that in the year 2000, more people died in the country from low educational attainment (245,000) than heart attacks. In addition, 176,000 deaths were due to racial segregation, 162,000 to low social support, 133,000 to individual-level poverty, 119,000 to income inequality, and 39,000 to area-level poverty.

In other words, if we’re going to assume everything the pope says is about us, then we have to take the bitter with the sweet.