ROME – Pope Francis said on Saturday that many Christian communities around the world suffer persecution because of the devil, who’s behind the hatred of the Christian faith that drives oppressors to lash out.

“With his death and resurrection, [Jesus] rescued us from the power of this world, the power of the devil, and the prince of the world doesn’t want this,” Francis said.

“Because we were saved by Jesus, and the prince of the world doesn’t want this, he hates us and provokes the persecution,” the pope said.

Francis was reflecting on a passage of the Gospel read during a prayer service for the Christian martyrs, in which Jesus, “who is the teacher of love,” speaks about hatred: “The world will hate you, but know that before hating you, it hated me first.”

Martyrdom, the pope said departing from his prepared remarks, “is a grace from God, not courage.”

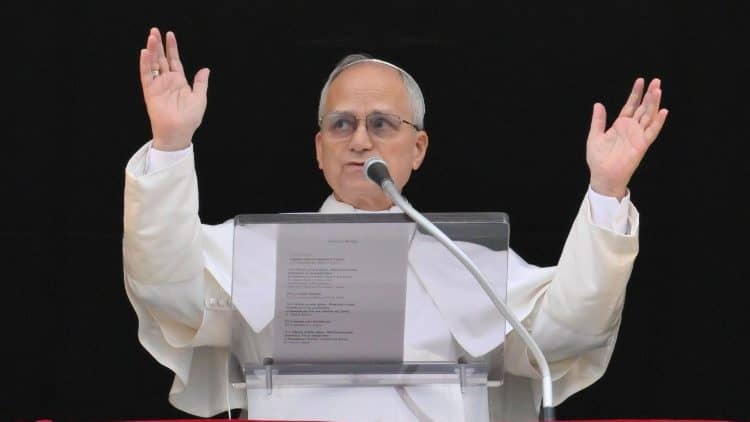

Pope Francis was speaking at Rome’s St. Bartholomew Basilica, which sits in an island on the Tiber river. The church, run by the Community of Sant’Egidio, has been dedicated to the New Martyrs since 2000, when St. John Paul II gave it that purpose.

The pontiff was taking part in a prayer service. His remarks came after three people closely linked to Christianity’s recent victims of persecution gave witness of their own experiences.

These included Roselyne Hamel, sister of Father Jacques Hamel, murdered last year at 85, while he was saying Mass in France; Francisco Hernandez, who spoke about William Quijano, a 21-year old man killed in El Salvador in 2009, for trying to keep young people out of gangs; and Karl A. Schneider, son of Paul Schneider, the first Protestant minister to be martyred by the Nazis.

The ceremony was full of symbolism. Upon entering the church, Francis went straight to an icon representing modern-day martyrs, from victims of Nazism and Communism. Throughout the service, he also wore a stole that belonged to Chaldean Ragheed Aziz Ganni, who was murdered in Mosul, Iraq, in 2007.

After the prayer service, the pope walked through the church, lighting a candle and saying a short, silent prayer in each of the six chapels across the basilica. In each, different martyrs from the 20th and 21st centuries are remembered, divided by continents. Two other chapels are devoted to the victims of Nazism and Communism.

In accordance to Saint’ Egidio’s ecumenical outreach, not all the martyrs were Catholics, but also Orthodox, Anglican and Christians of other denominations, who’ve “given witness of unity in their martyrdom” as the closing prayer intentions said.

In his address, Pope Francis also said that the Church today needs martyrs, just like during the hard moments of history some have said, “Today the nation needs heroes.”

“What does the Church need today?” he asked, before responding: “Martyrs, witnesses, this means, every-day-saints, those who lead ordinary lives, carried forward with consistency; but also those who have the courage to accept the grace of being witnesses to the end, to their death.”

The living heritage of the martyrs, Francis said, “gifts us today peace and unity. They teach us that, with the strength of love, with tenderness, you can fight bullying, violence, war, and that with patience, peace can be achieved.”

Andrea Riccardi, founder of the Comunity of Sant’ Egidio, delivered the opening remarks. As he noted, the day of the prayer, April 22, also marked the anniversary of the kidnapping of two Metropolitan bishops from Aleppo, Syria: Youhanna Ibrahim, Syriac Orthodox Metropolitan, and Boulos Yazigi, Greek Orthodox. They have been missing since 2013.

In front of modern-day martyrs, Riccardi said, “there is some shame in us: they are our contemporaries, sometimes even friends … Like Christian de Cherge, killed in 1996 when – with his brothers- stayed in Algeria to live with the Muslims. Like Shahbaz Bhatti … We were their friends, but we did not get rid of the willful will to save ourselves.”

De Cherge was a French Roman Catholic Cistercian monk, one of the seven from the Abbey of Our Lady of Atlas in Tibhirine, Algeria, who were kidnapped and believed to have been later killed by radical Islamists.

Bhatti was a Pakistani human rights activist, politician, and devoted Roman Catholic, killed for being a “known blasphemer.” He dedicated much of his life to advocate in favor of Pakistan’s highly oppressed minorities. He also pushed for the abolition of the blasphemy laws and the release of Asia Bibi.

RELATED: Killed for love: How new martyrs showcase new kind of martyrdom

One cannot remain detached, Riccardi said, in a world “where war is the mother of pain and poverty, where weapons are played with, [and] in which Christians are killed.”

Among those present in the packed church was Albanian Cardinal Simoni, who spent decades in prison and forced labor, and who was sentenced to death twice. The pope met him during a visit to his country, and made him a cardinal last year.

RELATED: Twice sentenced to death, Albanian priest is now a cardinal

Hamel, the sister of the priest who had his throat slit by two terrorists in 2016, described this martyr as someone who, at his age, “was fragile but also strong. Strong in his faith in Christ, strong in his love for the gospel and for the people, whoever they were, and I am sure, for his killers as well.”

She reiterated the words Francis used in a homily for a Mass in Hamel’s honor, where he said that at the time of his death, the priest didn’t lose his lucidity, and said that “the true author of persecution […] is Satan.”

There’s a paradox in his death, the priest’s sister said: “He who never wanted to be in the center gave a testimony to the whole world,” one that inspired countless acts of solidarity and love.

Before closing his homily, Francis said he was adding an icon to the many already present in the church, one of a woman whose name he doesn’t know, but who “looks down on us from heaven.”

He told the story of a Muslim man with three kids, whom he met last year, during his trip to the Greek island of Lesbos to show a light into Europe’s refugee crisis. The man’s wife, Francis said, was a Christian, beheaded by terrorists when she refused to throw away a cross she was wearing.

“I don’t know if he’s still in Lesbos, or if he was able to run away from this concentration camp, because the refugee camps, many times, are concentration [camps], for the amount of people left there,” Francis said.

For those in power, he added, always off-the-cuff, international agreements are “more important than human rights.”

“And this man didn’t have resentment. The Muslim, who had this cross of pain, carried forth with no resentment, found refuge in the love of his wife, who received the grace of martyrdom.”

After the prayer service, Francis greeted a group of migrants who have arrived in Italy with the help of Saint’ Egidio. Greeting the crowd gathered at the door of the church, he once again spoke about the migrant crisis, praising Italy’s southern region and Greece for their efforts on this issue.

“It’s true: We are a society that doesn’t have children, but we close the doors to migrants. This is called suicide,” he said.