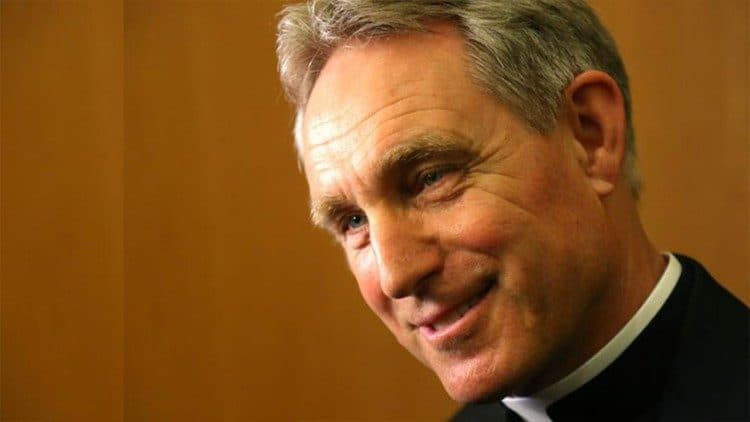

ROME – Pope Benedict XVI’s longtime private secretary, German Archbishop Georg Gänswein, spent the Feast of the Epiphany at a small parish in northern Italy, telling parishioners that Benedict was a man of prayer and debunking conspiracies behind his historic resignation.

Speaking to churchgoers at Sacred Heart Parish in Carnovali, Bergamo, on the Jan. 6 feast of the Epiphany, Gänswein described the late pontiff, who died on Dec. 31 of last year at the age of 94, as someone “whose vocation was that of a university professor and not an ecclesiastical career.”

“He was not born to exercise power,” Gänswein said, but insisted that once elected and faced with troubling issues in the church such as the pedophilia scandals, “He had a strong sense of responsibility: already as cardinal he saw that the big problem of the Church were not the persecutions or attacks from outside, but the filth that was produced inside.”

Awareness of this “cost him a lot,” Gänswein said, saying, “We never saw him cry because he was very controlled and dominated his emotions, but he suffered.”

Gänswein debunked various conspiracy theories surrounding Benedict’s historic resignation from the papacy in 2013, which Italians broadly still believe, saying that when Benedict confided his decision to resign, “It was a very hard blow.”

“I told him: Holy Father, you cannot do it. But he explained that he had fought and had suffered, but he no longer had the physical and psychological strength to exercise that responsibility,” Gänswein said, stressing that, “The gay lobbies, the IOR, pedophilia, Vatileaks, have nothing to do with it.”

Benedict, he said, “did not run away, he said, ‘my pockets are full,’ but he resigned out of love for God and for the Church.”

From the very beginning, Gänswein said Benedict believed that his papacy would be short due to his age, as he was 78 when elected, and that after his resignation, “he was convinced that he would not live longer than a year.” He lived for almost 10 years after stepping down.

Gänswein, 67, a conservative widely seen as a critic of Pope Francis, was sent back to his native diocese of Freiburg by Francis last year with no official job.

He returned to Italy for the first anniversary of Benedict XVI’s death and celebrated a Dec. 31 Mass for the occasion in St. Peter’s Basilica, with Cardinals Gerhard Müller, who is retired, and Kurt Koch, Prefect of the Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity.

In his homily that day, Gänswein described Benedict as a “shining example” for Christians and thanked Benedict for his life and witness, saying, “We also remain connected with Benedict XVI. In sincere gratitude to God for the gift of his life, the richness of his teaching ministry, the depth of his theology and the shining example of this simple and humble worker in the vineyard of the Lord.”

Noting that Benedict wished to spend the remainder of his years after resigning in prayer, Gänswein said prayer became an increasing focus of his life, with growing intensity and interiority as the years passed.

Benedict, born as Joseph Ratzinger, also tried to model his life after the virtues of Saint Joseph, Gänswein said, saying this was evident in his closeness to God and in his interaction with others, “relationships distinguished by great courtesy, humility and simplicity.”

Gänswein was invited to celebrate Mass for the feast of the Epiphany at Sacred Heart parish in Bergamo by the church’s pastor, Daniel Boscaglia, who met Gänswein while studying in Rome.

After celebrating morning Mass for the Jan. 6 feast, Gänswein later that afternoon held a public discussion in the parish hall titled, “Father Georg meets the city of Bergamo: testimonies, meetings and anecdotes from the voice of Benedict XVI’s secretary.”

The panel was moderated by Italian journalist Marco Roncalli, who attends the parish and is the great-nephew of Italian prelate Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, who in 1958 was elected Pope John XXIII.

Gänswein then led an evening Vespers service that culminated with a moment of Eucharistic adoration and blessing.

In the public converation, reported on in Italian media, Gänswein apparently dodged a question about Benedict’s relationship with Pope Francis, but said Benedict, despite his close friendship with Pope John Paul II, also had differences with the Polish pope.

“They spoke at least once a week, there were differences on the meetings in Assisi, canonizations, and other issues, but by discussing them they overcame them. John Paul’s pontificate without Ratzinger would not have been the same, for him he was a trusted friend and he recognized it publicly,” Gänswein said.

Noting that Benedict had gotten a bad reputation in the secular press over his strict crackdown on perceived doctrinal dissidents, with some dubbing him as “God’s Rottweiler,” Gänswein said that Benedict attended the Second Vatican Council as a young priest “and defended the real Council, while some wanted to interpret it.”

He pointed to the tension that developed between Benedict and Swiss priest and theologian Hans Kung, who served as a theological advisor during the Council but who was later sanctioned by the church for questionable theology.

“Hans Kung was envious, he told (Benedict) that from a progressive he became a conservative to make a career, but it wasn’t true, he just wanted to defend the true faith,” Gänswein said, saying that when Benedict was later elected pope, he didn’t have a specific plan of governance.

Benedict, he said, said he wanted “to put the question of God at the center of my pontificate, the rest can be sorted out. He was a person who can be summed up in three words: humble, meek, and intelligent.”

Gänswein said Benedict’s final years were spent in prayer with rosaries, spiritual contemplation, and the celebration of Mass, and that every now and then he watched the “Don Camillo” films by Italian journalist and cartoonist Giovannino Guareschi, which are a series of films produced in post-war Italy following the life of the protagonist, Don Camillo, and his parishioners in the small town of Boretto.

“By watching them, a German understands the Italian soul well, which hasn’t changed much since then,” Gänswein said, referring to the 1950s, when the series was first produced.

Guareschi, he said, “was an excellent theologian, he was better than certain professors who make speeches that are not understood.”

Gänswein also insisted that Benedict XVI, while often portrayed as stern and serious, was more lighthearted and joyful than people think.

“If you go to Google and write the word ‘joy,’ you get Benedict XVI as a result. For him it was a key word: faith is not a burden, but joy was one of his fruits, as was his subtle humor,” he said.

After 20 years serving as Benedict’s closest aide, Gänswein said that with Benedict gone, “I feel his spiritual omnipotence, but I miss his physical presence a lot.”