DUBLIN — In the five years he’s been in office, Pope Francis has drawn mostly enthusiastic reactions from the Church’s liberal wing, while conservatives tend to view him as playing fast and loose with long-standing Church doctrine. Now, however, some leading members of the LGBT crowd appear ready to join the critics, seeing this pope as not going far enough.

Many of those voices were out in force Monday afternoon at an event at Dublin’s Trinity College ahead of the Vatican-sponsored World Meeting of Families, set to culminate with a visit by Francis over the weekend.

Jamie Manson, a columnist and editor for the National Catholic Reporter who herself is part of the LGBT community, said that rather than being encouraged, she is disappointed by Francis and his 2016 post-synodal apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia, which she argued marginalizes gay and transgender people.

Speaking on a panel, Manson said many people have told her, “I should find great hope as a queer person” in Amoris, “but I do not.”

She quoted paragraph 251 of the document, which states that “as for proposals to place unions between homosexual persons on the same level as marriage, there are absolutely no grounds for considering homosexual unions to be in any way similar or even remotely analogous to God’s plan for marriage and family.”

Noting how the line was originally written by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who was elected Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, Manson said the fact that Francis included it in his exhortation is “a very, very serious problem because what that does is to create profound shame in LGBT people.”

“It communicates that your love is not capable of goodness or holiness in the way in which a heterosexual couple’s is, regardless of the way in which you love, regardless of if you show profound sacrifice…it does not matter because of your anatomy or your gender identity.”

Manson also pointed to Francis’s famous “who am I to judge” statement, saying the phrase, while initially taken as a sign of hope for LGBT Catholics, is unclear.

“What does that mean? We don’t even know what context that was in; was he talking about gay priests, was he talking about all LGBT people? We don’t know. Or when we hear that he secretly said to a gay guy, ‘God created you the way that you are,’ that’s all hearsay, and hearsay doesn’t inspire doctrine, it doesn’t give hope,” she said, referring to reports that during a private meeting with Chilean clerical abuse survivor Juan Carlos Cruz, who is gay, the pope had said God made him that way.

Pointing to high depression and suicide rates among LGBT people, Manson said they are also at risk from anti-gay legislation in places such as Africa, where many countries hold more traditional views on homosexuality and where at times laws allow gay people to be jailed or put to death.

“These are matters of life and death for countless people, so he has to speak,” she said, calling the pope’s silence on anti-gay legislation during his 2015 visit to Africa “one of greatest disappointments in this papacy.”

Manson, who is based in New York and holds a Master of Divinity degree from Yale, also spoke at a press conference held at Trinity College to launch a new academic research report on “LGBT Catholics & Gender Theologies,” supported by the Wijngaards Catholic Research Institute, a nonprofit think tank dedicated to academic research and education that examines Church teaching with the goal of “reforming” it.

Several speakers on Monday’s panel took issue with the fact that no LGBT organizations or groups were invited to speak at the event, arguing that their voices were not being heard.

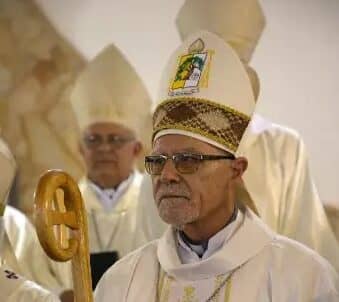

Father Tony Flannery, a Redemptorist priest who was suspended by the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith six years ago because of his controversial writings on women’s ordination, homosexuality and contraception, said he is eager to see Francis in Dublin, but believes the pontiff has not done enough to bring about change on women and LGBT issues.

“I know there is so much he hasn’t done,” Flannery said, but added that “for a man of his age, at this place and time and for what he’s up against, he has worked miracles.” He supported a statement made from a member of the crowd, who asserted that the pope “could be doing much more if he weren’t being blocked by the Curia.”

Hille Haker, chair of Moral Theology at the Loyola Institute in Chicago and a former professor of Christian ethics at Harvard Divinity school, said that while she is supportive of the pope’s stance on issues such as climate change and the global economy, “when it comes to the question of gender, and when it comes to the question of the Church governance and structure, this pope is really very, very disappointing to me.”

Speaking on contraception, she said the Catholic Church is living “in a false world,” because while current teaching holds that it’s “evil” because it prevents procreation, this stance is based on a “flawed theology” which does not consider the social, political and relational benefits.

Citing relational strains, the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and the general use of birth control in women’s healthcare, Haker said the Church needs to reform its teaching on sexual morality, and “it should not be done by the clerics.”

Pointing to Pope Paul VI’s historic 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae that reiterated the traditional ban on contraception, she said the document “has to go, it has to go. Full stop.”

On the exclusion of divorced and remarried Catholics without an annulment from Communion, Haker said “it is scandalous what the Catholic Church does, and it is un-Christian.”

“Certainly it is not justified by any Biblical reading, and it is irrational. The only sense you can make of it is that it is a terrorizing regime of power…we need to unlearn a lot of things and reach out as human beings who can support each other.”

Siobhan Garrigan, a professor of theology at the Loyola School of Religion, spoke about the topic of women’s ordination to the priesthood, saying women are often “marginalized” in the Church and are not given a chance to have “actual influence” in positions of leadership.

She complained that during this year’s WMOF events, women “are not as visible as they were in the visit of John Paul II in 1979,” when both laywomen and nuns were running committees and activities.

“Women’s bodies are feared, and women’s voices are really feared,” she said, arguing that this fear is rooted in the Church’s “overt” theology on gender and an overly-masculine conception of God. The Vatican’s teaching is “misogynist [and] infantilizing,” she said, adding that reform of the Church’s sacramental theology is where the question of ordination needs to begin.

Luca Badini, director of research at the Wijngaards Institute, said the exclusion of women and the clerical sexual abuse crisis both can be attributed to a strong clericalist mentality in the Church’s hierarchy.

Clericalism, he said, is a “caste system, it is a spiritual apartheid” and “a sin” preventing women, and laity in general, from being fully part of the Church or taking seats on important ecclesial groups and commissions.

This clericalist structure in the Church is one of the reasons that allowed the current abuse crisis, which is “in a different league” than before with the revelation of new scandals in Pennsylvania, he said.

In terms of how changes in Church teaching can be achieved, panelists suggested a wide range of possibilities, including protests and the withdrawal of monetary donations.

In her opinion, Garrigan said a first strategy is to “pray like mad and to protest in both overt and subtle ways.”

“Ladies, all that cleaning, all that support, go on strike. In a heterosexual relationship, withdraw sex, because that will make the man in your life get on board,” she said, adding that if women really want to “kick them where it hurts, stop giving money.”

Similarly, Badini said this is a war “fought with your wallet,” and urged LGBT Catholics to stop donating to the Church until they see change.

“There are a few things we can do, but talking with your wallet is one. Withdraw donations. I’m not saying stop giving charitably, but find other worthy causes to give to.”

Haker weighed in, saying small steps toward change have already been taken, but “we should say no, no to the moderate, tiny little reforms here and there. What we want is actual representation; that’s what we want, and if we don’t get it now, then we won’t get it. The momentum is now.”