This Friday, an event of global Catholic significance will take place in the unlikely setting of Canale d’Agordo, a small Italian town in the country’s northern region of Veneto with scarcely more than 1,200 residents.

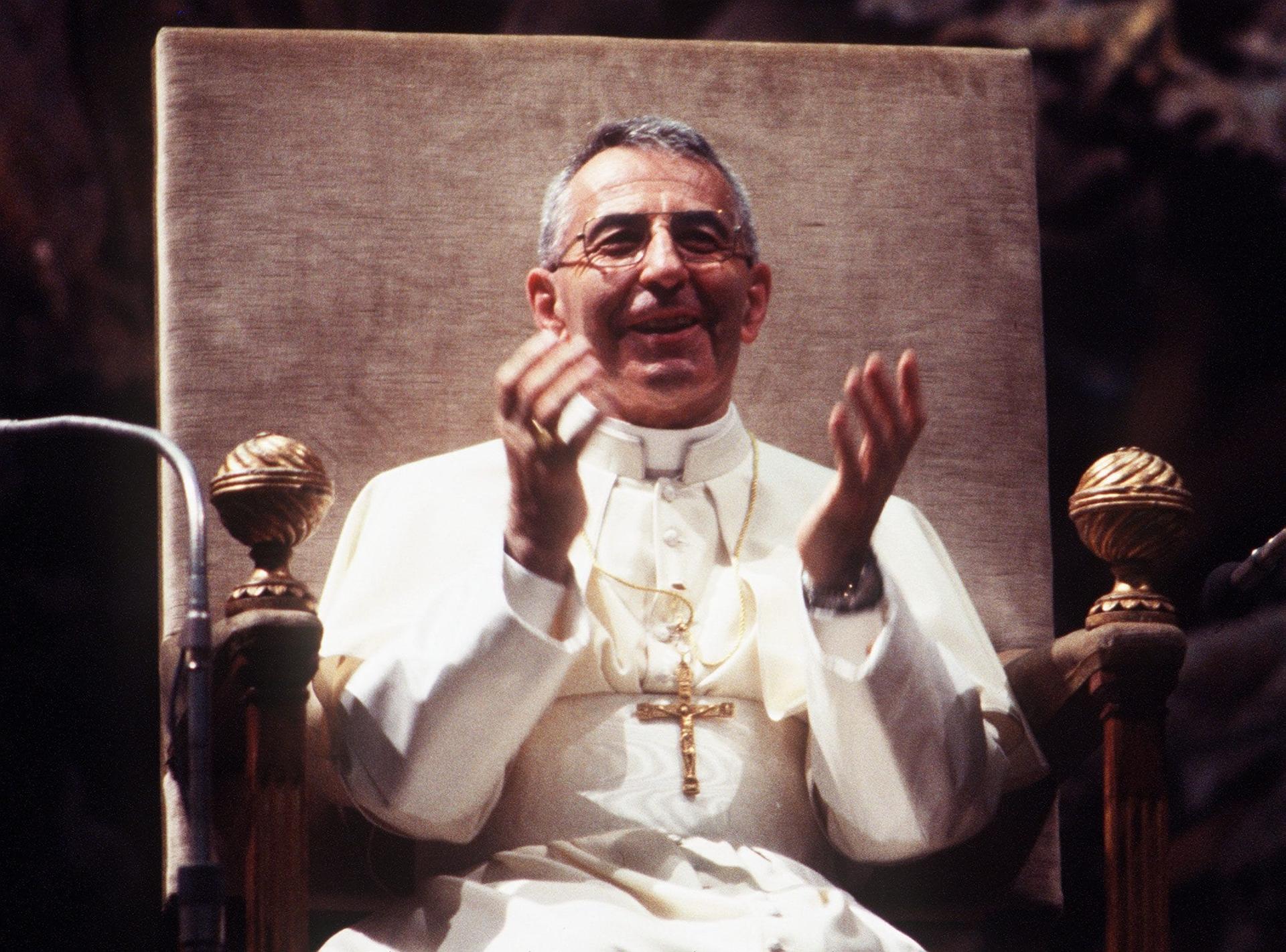

On that day, a museum in honor of the town’s most famous son will be formally opened. It’s called the “Albino Luciani Museum,” a figure better known to the world by the name he took when he was elected to the papacy 38 years ago on August 26, 1978: Pope John Paul I, the “Smiling Pope” of 33 days.

Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, who himself grew up in Veneto roughly 70 miles away, and who is today the Vatican’s Secretary of State, will celebrate a Mass just before the inauguration ceremony.

Although there’s been a photo exhibit in Canale d’Agordo since 1978, the goal of the new museum is to collect important documents, objects and other items associated with Luciani, so it becomes not only a tourist destination but also a center of scholarly research.

Naturally, the museum also wants to demonstrate how Luciani’s personality and outlook were shaped by the Valle del Biois region of Veneto in which Canale d’Agordo is located. Plans call for the eventual construction of a facility for pilgrims, a conference center, and a day home for the elderly.

As I’ve written before, John Paul I is the greatest Rorschach test in recent Catholic experience.

Because his papacy ended before it had really even begun, viewers are free to project their own hopes, dreams and fears onto him – he would have been a liberal reformer, or a wolf in sheep’s clothing; he would have been another John XXIII, or another Pius X; he would have been the one to clean out the Vatican’s stables, or the last gasp for the old guard, and on and on.

As a result, his legacy is a bit ephemeral and hard to nail down, and almost by definition anything one says about it is speculative.

However, there’s a good case to be made that there’s a special spiritual kinship between John Paul I and Pope Francis, one which suggests that Luciani is something of a role model and source of inspiration for the current occupant of the office.

Mercy is, of course, the spiritual Rosetta stone for Francis, and earlier this year an interview book with the pope was released called “The Name of God is Mercy,” published simultaneously in 80 languages and laying out his vision for his special jubilee year.

It was striking that in the book, Francis cited all of the popes since the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), but the one he quoted the most was John Paul I – referring to him, as Italians generally do, as “Papa Luciani.”

Among other things, Francis quoted a line from a homily Luciani gave in 1958, when he was named the bishop of Vittorio Veneto by St. John XXIII. In it, Francis recalled, Luciani said he had been chosen “because the Lord preferred that certain things not be engraved in bronze or marble but in the dust, so that if the writing had remained it would have been clear that the merit was all and only God’s.”

Francis, for whom not taking himself too seriously is a defining virtue, was obviously impressed.

It’s no surprise that Francis would be drawn to the figure of Luciani. For one thing, Francis is keenly conscious and proud of his family’s Italian roots, and the Bergoglio clan hails from the hills of Monferrato in the Piedmont, about 280 miles on a straight line across the northern part of the peninsula from Luciani’s home in Veneto.

As a result, the Bergoglios and the Lucianis would have shared much of that northern Italian Catholic ethos of the early 20th century – pastors who were earthy and accessible, bishops who were socially conscious and engaged, a Church rooted in the experiences and faith of its people.

As an expression of that formation, Luciani during his brief reign pioneered the simplification of the papacy by dropping the royal “we,” declining coronation with the papal tiara, and initially discontinuing use of the sedia gestatoria, or portable throne. (He was later persuaded that it was needed to carry him through St. Peter’s Square for his audiences so people could see him.)

Luciani also charmed the world by using simple, direct pastoral language in his public addresses, sometimes irritating theologians and canonists with ambiguous soundbites they worried might be open to misinterpretation, such as his famous line that God is so merciful as to be “even more” a mother than a father.

That, of course, sounds remarkably like another pope we know.

All of this suggests that the opportunity created by the opening of the new Luciani museum isn’t just of historical or biographical interest. It’s also of relevance to current events, because there’s a sense in which Pope Francis probably understands himself to be leading the papacy John Paul I might have given the Church, had there been but worlds enough and time.