Quite often, perceptions of a pope’s social agenda are driven at least as much by how they happen to intersect with someone’s domestic political interests, rather than what’s truly most urgent from the pontiff’s own point of view.

As the American debate over gay marriage heated up a few years ago, for instance, absolutely anything Pope Benedict XVI said about marriage being between a man and a woman would make headlines, regardless of how central it was to whatever point the pope was actually trying to make that day.

Similarly with Pope Francis, during the recent Trump v. Clinton campaign, any statement whatsoever he made that used the word “walls” got spun up into a political shot across the bow, no matter what context or scope the pontiff himself was giving the term.

One consequence is that clear papal priorities which don’t happen to pack much political wallop at the moment tend to be either ignored or played down – not because the pope isn’t in earnest, but simply because we’re not paying attention.

Take, for instance, the matter of prison reform.

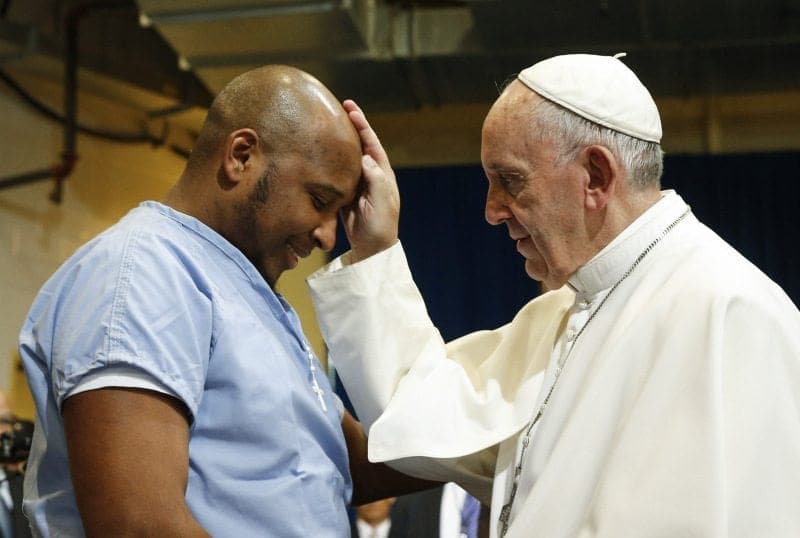

If one were to compile a list of the top five social and political preoccupations for Pope Francis, the welfare and rehabilitation of the incarcerated would almost certainly have to make the list. Just two weeks after his election in March 2013, the new pope visited a youth detention facility in Rome to celebrate Holy Thursday to wash the feet of twelve inmates, including Muslims and women.

Since then, visits to prisons have become a standard feature of papal travel, including a celebrated stop at the “Centro de Readaptación Social No. 3” in Juarez, Mexico, this past February.

Flash forward to earlier this month, when Francis essentially closed his Holy Year of Mercy with a special jubilee event for prisoners, featuring 1,000 prison inmates from around the world, including some 50 from the United States, who traveled to Rome with their families, along with people who work in the penitentiary system and as prison chaplains.

In between, Francis has missed almost no opportunity to insist that sending someone to jail should never be a purely punitive move, but it should aim at their eventual reentry into society.

He’s called on governments to show clemency, he’s urged an end to the death penalty, and he’s demanded improvements in prison conditions to better respect the “human dignity” of inmates.

For obvious reasons, those gestures and statements haven’t elicited quite the reaction in the United States as Francis’s positions on immigration and climate change, simply because prison reform isn’t as sexy a political topic.

Sometimes, however, when a pope’s determination on an issue intersects with a growing realization that the status quo isn’t working, the conventional political calculus can change.

To take the best-known example, think about how different the world looks today because of the convergence in the 1980s of St. John Paul II’s moral opposition to communism and America’s realigned foreign policy priorities under Reagan.

All of which brings us to what’s happening tomorrow in Ferrara, a city in northern Italy.

There, for the first time in history, a “flash mob” will be staged in an Italian men’s prison, in this case the Costantino Satta detention center.

Some fifty inmates will take part, including Greeks, Romanians, Moroccans, Tunisians, Tanzanians, Italians, and even a couple of Brits and Canadians, representing a variety of different religious backgrounds as well, such as Catholics, Muslims, Orthodox, Buddhists and atheists.

For the record, the flash mob is not a work detail forced upon the inmates, but something they voluntarily decided they wanted to do.

Charmingly, the prisoners will perform a zumba-style routine of spins, funky steps and arm swings set to the tune of “Pope is Pop,” a song written about the pontiff by Italian composer Igor Nogarotto. (Nogarotto, by the way, describes himself as “not religious,” but says he finds Francis to possess “amazing charisma” as a man “humble and close to the people.”)

The official idea of the flash mob is to mark the close of the jubilee year, but obviously the inmates are also hoping it will draw attention to the pontiff’s leadership on prison reform.

In a sense, tomorrow’s event forms a bookend with another flash mob in a prison that took place in October 2015 to mark the opening of the jubilee year, in that case the Rebibbia women’s prison in Rome.

In the social media-dominated world of the early 21st century, it’s hard to think of a savvier way to spotlight a papal message than packaging it with a flash mob, a zumba routine and a tune called “Pope is Pop.”

This celebration in an Italian jail is one small but telling sign of ferment around the pope’s vision on prisons, and it comes at a time when Americans in particular may be increasingly ready to listen.

Famously, the United States leads the world in incarceration rates, with just five percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of the total number of people behind bars.

Almost half of those inmates are drug offenders, and relatively few are major “pushers” but people guilty of comparatively minor offenses.

Although movement at the national level may be hard to find, several states have already had success with reform measures.

Texas, for instance, recently abandoned plans to build new prisons and instead invested in drug courts, treatment and mental health services. As a result, Texas has cut its inmate population significantly and saved more than $2 billion, while violent crime rates have dropped.

It would not be surprising if one day soon, inmates in American prisons were to stage their own pope-inspired flash mobs – and perhaps, in tandem with other creative ways of getting the message across, something big could result.