BUENOS AIRES — Awakening in the darkest part of Tuesday night to the Trump earthquake, I had the same tightening of the stomach, the same vertigo, I had felt the night of Brexit.

This time, it was not my country involved, so I should have been less alarmed. Yet Trump is far, far bigger.

Few doubt that his triumph is the overturning of an order, part of a wider earthquake whose tremors are being felt across the western world, unseating globalism and liberal, technocratic politics.

It is a nationalist rebellion that has triumphed precisely in the most successful countries, the English-speaking nations that have apparently benefitted most from globalization.

We’ve been here before. The parallel, historically, is with the 1920s-30s, which saw firstly a crisis of capitalism and social upheaval that could no longer be contained, unleashing new movements that would end up being controlled by nationalist demagogues, and leading eventually to war.

Here in Argentina, it produced a leader and a movement which overshadowed Pope Francis’s adolescent years, and that would profoundly mark him.

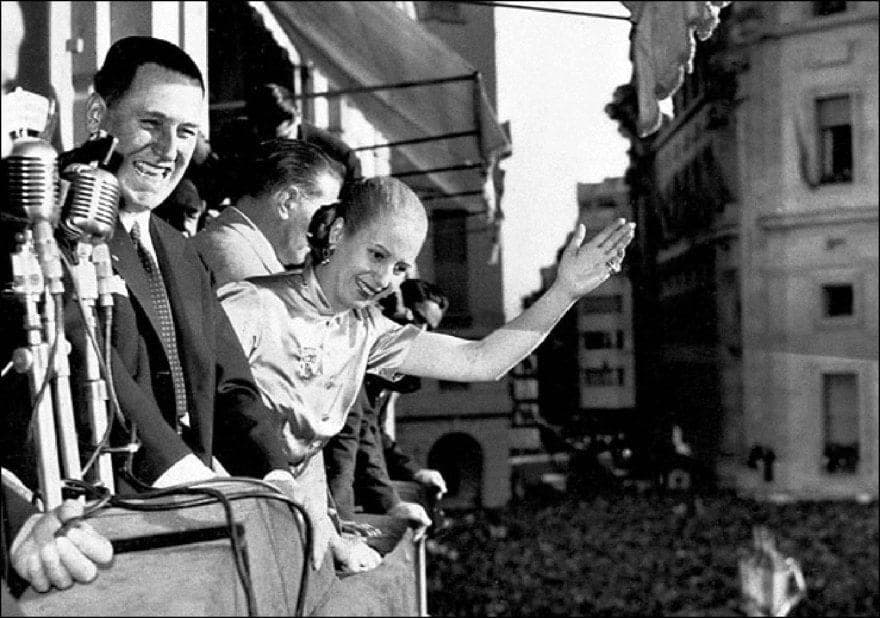

In February 1946, Colonel Juan Domingo Perón pulled off a stunning electoral victory not dissimilar to Trump’s. He was carried into the presidency by a galvanized working-class and lower middle-class despite the fierce united opposition of the entire political establishment, from conservatives through to communists.

The more the political elite and the media poured scorn on this upstart colonel, the more ordinary people — the disenfranchised and the jobless as well as the children of immigrants, on the rise but excluded from power — trusted him to be on their side.

Peronism would never have happened without the economic shocks of the early 1930s, just as Trump would never have happened without the 2008 crisis. Even though the economies of both Argentina then and the US since were quick to recover, the crisis of trust and inequality the shocks exposed marked a whole generation.

Whether un-unionized, poorly paid workers in 1940s Argentina, or white workers in depressed areas in 21st-century America and the UK, ordinary people looked for a champion who would put their interests first.

Sick of slick, they put their faith in outsiders, whose plebeian lack of gloss is their strongest selling-point. What the elites call demagoguery feels to their supporters like authenticity.

The fact that their champions are hardly like them, socially speaking, matters little. Nigel Farage of the UK Independence Party and Donald Trump may be financial and property speculators, but they are ‘blokes’ and ‘guys’ unfettered by political correctness — not lofty and remote like the liberal elites.

Trump, like Perón in the 1940s, opens up politics to two major forces excluded by the liberal-technocratic order: religiosity and nationalism.

Neither Perón nor Trump is personally religious, yet both understand the importance of faith to ordinary people and communities, in contrast to the ideological deafness of the democratic parties in 1940s Argentina or (spectacularly) the U.S. Democrats in 2016.

The assumption of liberal elites is that religion is something to protect politics from rather than to renew politics with. (Tim Kaine’s watery stance, “personally opposed but publicly in favor” of abortion, was a perfect example in this election.)

Trump’s faith may be non-existent, just as Perón showed no interest in Catholicism before it became politically useful to him, but that’s not the point. They understand that faith and nation offer an ethos at a time when all appears to be fragmenting and relativistic, when liberal elites appear to offer little beyond self-interested individualism and an ethic of autonomy.

Brexit and Trump, like Peronism, are revolutionary because they upset the existing order. But they are essentially conservative in valuing community, nation, family and faith. (Marxist scholars of Peronism have long been befuddled by working-class Argentines apparently voting against their own economic and political self-interest).

What Brexit and Trump show is that, as Jonathan Haidt noted in a perceptive article, the battles now — just as in the 1930s-40s — are no longer between left and right but between globalists and nationalists.

It’s not primarily about the economy. True, those who have done badly — or seen their incomes freeze over the past decades — are not invested in globalization the way its beneficiaries are. But the main driver of change is the desire for values and identity.

Globalization — with its accompanying ethos of anything-goes tolerance, celebration of diversity, and contempt for local loyalism — weakens ties, breaks up community, and provokes resentment. It provokes an assertion of the value of belonging (flags, faith and family), and of local attachment: “taking back control” in the slogan of Brexit, or Trump’s “make American great again.”

Immigration is the target of contemporary nationalism, because foreigners stand for globalism. They represent the intrusion of the other, the arrival in our midst of different values that violate our worldview.

The last time the share of foreign-born in America reached current levels, the Ku Klux Klan had 6 million members – mainly in northern states concerned about Catholic immigration.

A breakdown of both the Brexit and Trump votes shows that immigration, not poverty or inequality, was the main concern of those voting most passionately for change. Trump’s border wall and his promise to “shut down” Muslims from terror zones were grotesque, but highly effective, ways of addressing this concern on the campaign trail.

Inevitably, he will try to deliver on both, just as, post-Brexit, the British prime minister, Theresa May, knows that whatever other terms she negotiates with the European Union, they cannot include the free movement of people. Two of the richest nations in the world are now bent on building walls and closing doors.

After Pope Francis’s visits to Lampedusa and Lesbos, and his constant urgings to wealthy nations to keep their doors open to those in need, it is tempting to assume he is an unreconstructed globalist. Yet everything in Francis’s past locates him as a nationalist sympathetic to Peronism, at least in its early incarnation.

He is fiercely loyal to his place of birth, and a consistent opponent of a globalized capitalism devoid of nationality, face or culture. He is no globalist.

He knows at first hand the importance of work and family. He deeply values faith and nation. And he has been a fierce critic of a detached, ideological politics, whether of left or right, that fails to be rooted in the values and interests of ordinary people.

But he knows the dark side of this nationalist politics, and its tendency to divide the world into those who are in and those who are out.

Perón was not anti-immigration as such — most of the foreigners had arrived by 1930, and came in drabs afterwards. But he understood the value of exalting the local at the expense of the foreign, and the power of scapegoating. The elites were labeled as extranjerizante, ‘foreignizing’, or vendepatrias, people who would sell their country to make a quick buck.

Peronism at its early best opened up politics to the deeply-held values of ordinary people, created work and raised standards of living for the poor, and gave women the vote. Its ‘ideology’ was even explicitly based on Catholic social teaching.

But at its worst, especially in the 1950s, it was dictatorial and polarizing. (Eventually Church and Perón clashed).

Faced with the new nationalist politics, Francis will insist you can be both loyal to place yet open to the other. You can be welcoming and assimilationist without surrendering your sense of self.

The Catholic Church itself represents the balance between globalism and nationalism. It values place, loyalty, faith and family, and dislikes the way liberal globalism has sought to undermine these.

Yet it is attentive to the needs of the vulnerable outsider. As he has already done in his remarks to Eugenio Scalfari, Francis will urge the U.S. and other countries not to turn their backs on the needy fleeing war and hunger.

Because of his Peronist background, Francis will grasp what lies behind the rejection of liberal politics by ordinary people, and the drive to rebuild community and a sense of place. He has long rejected a ‘liquid economy’ that assumes unemployment and job insecurity as the price of free markets.

But as he will surely remind Trump when they meet, secure nations are not those that build walls, but bridges.