LINCOLN, Nebraska — Victims of sexual abuse at the hands of Catholic priests urged Nebraska lawmakers on Friday to pass a law that would let people who were abused decades ago file lawsuits against the church or other organizations that were negligent.

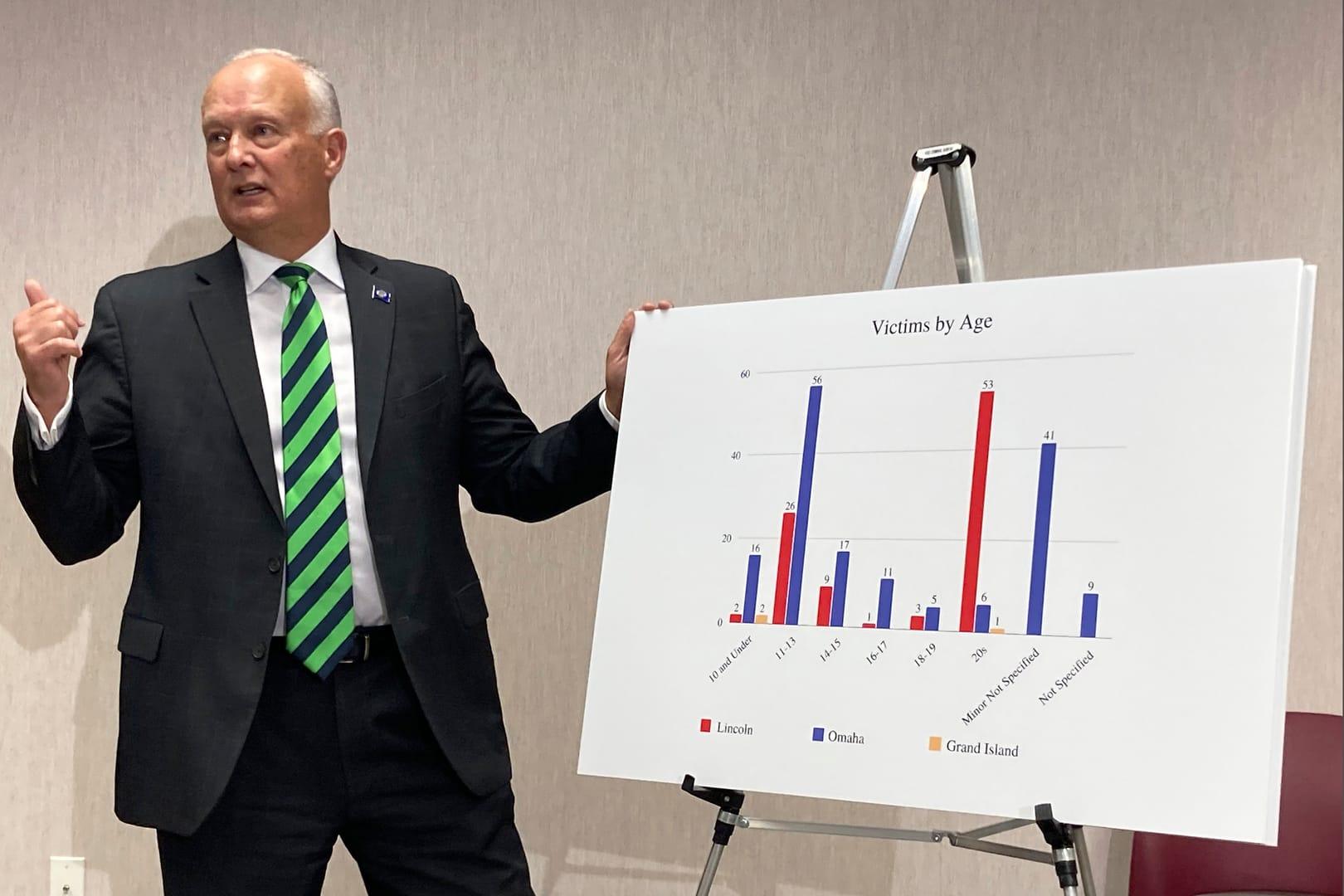

The proposal comes on the heels of a Nebraska attorney general report that identified 258 victims who made credible abuse allegations against church officials, dating back decades. None of those cases, however, are expected to result in prosecutions or legal judgments because the statutes of limitation for both criminal charges and civil lawsuits have expired.

Members of the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee are now reviewing a bill that would eliminate the statute of limitations for lawsuits. The sponsor, Republican Sen. Rich Pahls, of Omaha, said the measure is a start of a multiyear push to bring justice for victims of abuse.

Pahls said the attorney general’s report shows the need to bring more accountability to institutions such as the Catholic Church, the Boy Scouts of America, or USA Gymnastics, which have all been rocked by child sex abuse scandals. He pointed to his own experience as a former principal at Millard Public Schools, where educators are governed by mandatory reporting laws.

“If we knew there was abuse going on and didn’t report it, we’d get in trouble,” he said.

If it passes, Nebraska would become the 18th state to abolish statutes of limitations for such civil actions in child sex abuse cases, said Kathryn Robb, the executive director of Child USAdvocacy.

Another 27 states have passed “revival laws,” which expand statutes of limitation and let victims file lawsuits if their claim had expired under the previous time window. In Nebraska, child sex abuse victims can file lawsuits until they turn 33.

Robb, a child sex abuse survivor, said many children suffer devastating, long-term consequences after they’re abused and may go for decades without telling anyone what happened to them. The trauma may manifest itself years later as post-traumatic stress, eating disorders, substance abuse or running afoul of the law.

“Why should perpetrators and other bad actors be protected by the passage of time while the victims suffer in perpetuity?” she said.

Stacy Naiman, who said she was groomed and molested in 1999 by an O’Neill priest who was also her religion teacher, said the priest was never charged and can’t be sued under current state law. Naiman said she suffered from severe depression and anxiety after the abuse and attempted suicide.

“I was devastated, defeated and lost all hope for justice,” she said. The pending bill “will force (the church) to confront their inaction.”

The bill drew opposition from Nebraska’s Catholic Church and the state’s insurance industry, which would likely have to make large payouts for decadesold abuse cases if the measure were to pass.

Tom Venzor, executive director of the Nebraska Catholic Conference, said the church is “profoundly sorrowful” for the pain inflicted on victims, but he argued that statutes of limitation are designed to ensure that institutions don’t face decades-old lawsuits involving people who are no longer alive and memories that may be unreliable.

“Statutes of limitation are an attempt to balance the interests of plaintiffs and defendants,” he said.

Korby Gilbertson, a lobbyist for the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, said the bill could lead to lawsuits against organizations under new leadership that wasn’t involved with previous offenses. She also noted that civil cases have a lower standard of proof than criminal matters in which prosecutors must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

“The owner of that business may not be the same owner, may not have any knowledge of the crime that was committed,” she said.