A number of people close to Francis have been looking forward eagerly to a book out this week in Italy that is sure to lay to rest the myth that somehow, he lacks the philosophical and theological ballast to be pope.

Massimo Borghesi’s dazzling ‘intellectual biography’ of Jorge Mario Bergoglio shows that this criticism — born of a mixture of snobbery and ignorance, as he wrote in a recent article in the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano — is, whatever your view of Francis, simply wrong.

In his fascinating and deeply textured exploration of the pope’s thinking since the 1960s, Borghesi, who is professor of moral philosophy at Perugia University and the author of many studies of the dialectics of Romano Guardini, demonstrates that Francis’s straightforwardness is, as he puts it, “simplicity as a destination that presupposes the complexity of a profound and original thinking.”

That’s not news to me. In wading through his complex early writings for my biography of Francis, I was aware that I was in the presence of an astonishingly far-reaching intellect, one shaped by a pattern of thinking with deep theological roots. Yet until now that’s been hard to show because no one has given that thinking the systematic treatment it deserved.

The sophistication of Francis’s thinking has been obscured in part because giant Latin American Catholic intellectuals such as the Argentine philosopher Amelia Podetti and the Uruguayan thinker Alberto Methol Ferré — both very influential on Bergoglio — are off European and American Catholic academic maps.

It’s also because, as Francis’s longtime friend Guzmán Carriquiry, secretary of the Vatican’s Latin-American commission, points out in the preface to Borghesi’s book, Francis has never wanted to pass himself off as an academic, in part because of his own horror of intellectual abstraction, and in part because of his desire as a pastor to communicate in the language of simplicity.

So anyone trying to summarize the pope’s thought has to dig deep and range widely, as well as have a grasp of the complexity of dialectics. Borghesi is one of the few with the capacity and the commitment to undertake that task.

One immediate practical challenge is that, unlike John Paul II and Benedict XVI, Francis didn’t arrive in Rome with a clearly marked-out corpus anchored in a published doctoral dissertation. Francis’s output is almost entirely in the form of articles, talks, or homilies – which have taken the years since his election to compile and publish.

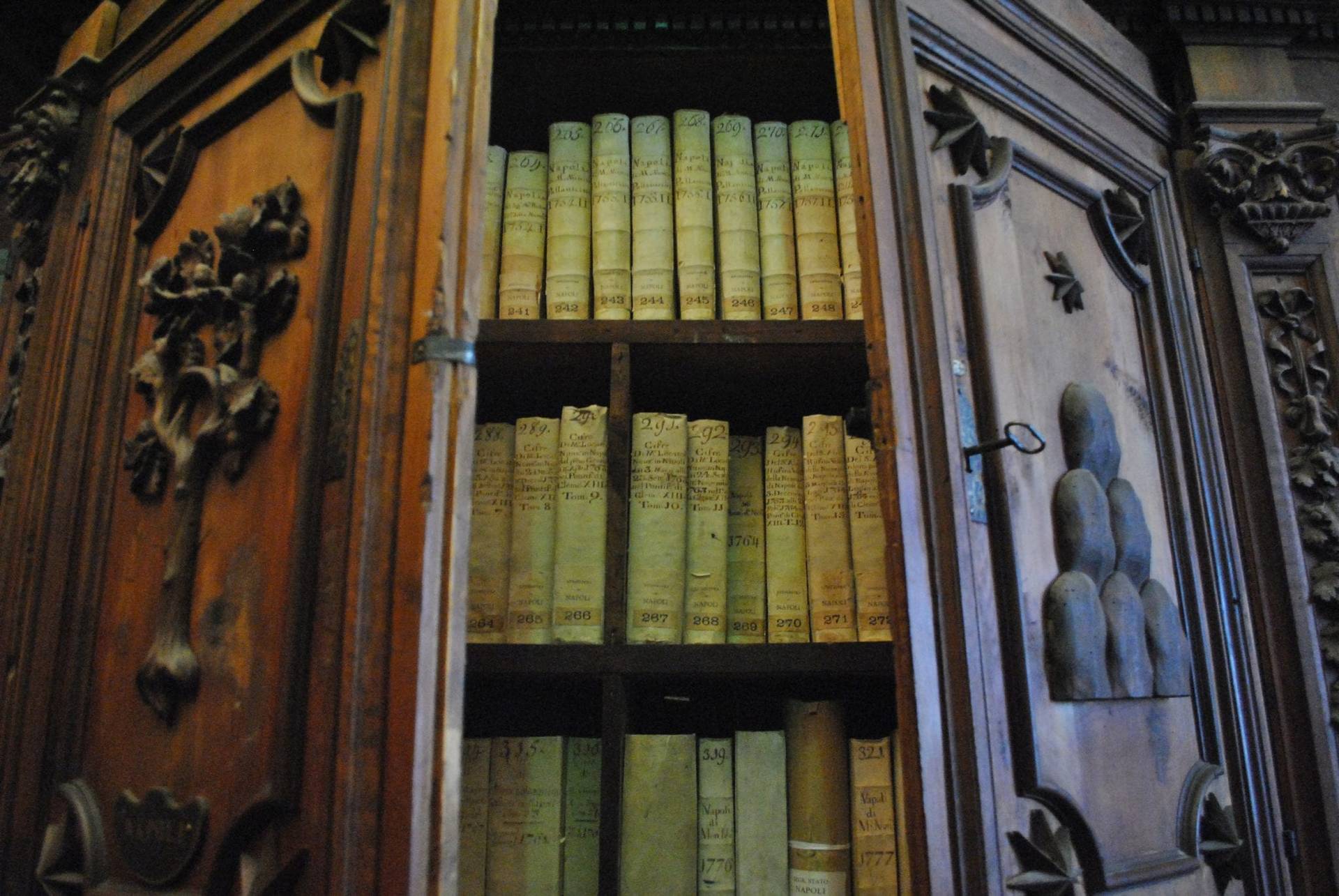

(When I arrived in Argentina a few months after Francis’s election in 2013 to research my biography of him, the Jesuits literally had to blow the dust off the three volumes of his writings from the 1970s and 1980s before handing them to me to photocopy.)

But while he didn’t come with a doctoral thesis defended in a university that was later published, he did have a thesis, which he began at the age of 50 after standing down as rector of the Colegio Máximo in Buenos Aires. It was a study of Guardini’s early work on philosophical anthropology, starting from the German theologian’s 1925 book on the reconcilation of polar opposites or ‘contrasts,’ Der Gegensatz.

The thesis wasn’t just begun in 1986 in Germany and abandoned after a few months, as some have claimed, but worked on intensively for a period of at least four years. But because that period coincided with – ironically – a polarization within the Argentine Jesuits over his leadership, Bergoglio never presented and defended the thesis prior to being made a bishop in 1992, although he has drawn heavily on it ever since.

Borghesi, who was helped in his research by Francis answering his questions via four recordings in January and March this year, has not seen the unpublished thesis — it’s not clear if anyone ever has — but can here reveal its title: Polar opposition as Structure of Daily Thought and Christian Proclamation.

The pope’s dialectical thinking is at the core of Jorge Mario Bergoglio: Una biografia intellettuale. Borghesi uncovers a huge canvas filled with many influences, from the Lyons Jesuits in the 1950s via Podetti and Methol Ferré and Guardini, through to, more recently, Hans Urs Von Balthasar and Luigi Giussani. Yet he rightly gives the major space to the development of Bergoglio’s dialectics, which he describes as the filo rosso, or “golden thread,” that holds it all together, forming an “original conceptual nucleus.”

Borghesi shows that “Bergoglio’s whole thinking is a reconciliation thinking” — not in an irenic, optimistic, naively progressive way but systematically. At the heart of his method is the notion of a synthesis, or fusion, of polar opposites, in a higher, or transcendent plane.

This is not, to be clear, Hegel’s model, in which on a philosophical plane two rival ideas battle it out and a third idea emerges that destroys both. It draws, rather, on the critique of Hegelian dialectics by the nineteenth-century Tubingen scholar Adam Möhler, later developed in the twentieth century by Guardini and two Jesuits in particular, Erich Przywara and Henri de Lubac.

In this, anti-Hegelian or Catholic dialectics, the Church is a coincidentia oppositorum, a place of reconciled diversity in which the Holy Spirit forges a synthesis on a transcendent plane of coexisting elements that pull in opposite directions. Such dynamic polarities are intrinsic to creation, and reflect a divine grammar.

(For an example of a “polar opposition,” consider sameness/change. I remain the same person yet I constantly change. Take away either of those elements, and I cease to be a human being; combined, we have a wonderful dynamic synthesis called life.)

Bergoglio’s fascination with polarities began in the 1960s, when he first began exploring as a Jesuit via Gaston Fessard’s 1956 monumental anti-Hegelian work on the dialectics of grace and freedom in St. Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises. Fessard, Francis tells Borghesi, “gave me so many of the elements that later got mixed in.”

Fessard was one of a 1950s group of Lyons-based jésuites blondéliens — that is, Jesuits inspired by Maurice Blondel — that included Henri de Lubac, Gaston Fessard and Michel de Certeau. Their journal, Christus, edited by Father Maurice Guiliani, shaped the renewal of Ignatian spirituality in Argentina led by the austere Father Miguel Angel Fiorito, Bergoglio’s spiritual director and his promoter within the province.

Borghesi shows that Bergoglio was drawn to the tension of polarities first of all through the Exercises, which encourage a person to operate simultaneously on two planes, to have faith as if all depended on God, yet to act as if everything depended on us. This classically Jesuit holding together of nature and grace — what Fessard called an “as-if” theology — allows the follower of Christ to be deeply in the world, yet open to the transcendent, to be, as the Jesuits synthetically put it, “contemplatives in action.”

The polarities here — immanence/transcendence, action/contemplation, in the world/not of this world — are maintained in tension, and a new synthesis emerges.

An example from Latin-American history that inspired Bergoglio and Methol Ferré was the encounter between indigenous Indians and Spaniards. The early conquest period was a classic example of the violence of contradiction, marked by brutality, exploitation and violence. But in a later period, the Jesuits founded a civilization in the reductions that created a new synthesis from both cultures, while respecting both — a distinctively Latin-American Baroque.

A person advances in the spiritual life by living in that incarnational tension, rather than trying to “resolve” the tension by opting for one pole over the other. Conversely, the diabolos, the divider, tempts people to see the polarity as a contradiction, in which two values or goods rival each other.

The battle over Amoris Laetitia — which Borghesi gets to at the end of the book — is a classic case of where a false opposition or contradiction has been created between mercy and truth, or between doctrine and pastoral practice. In fact, both need the other, and need to be held in tension, as Borghesi shows that Amoris seeks to do.

That continued tension is a sign of the truth of the Church, because truth is the union of opposites, just as heresy involves the absolutization of one pole or value in such a way as to break its bond with the other. (G.K. Chesterton once described a heresy as a good idea gone mad.)

The error of Hegelian dialectics — as well as Marxism and the logical positivism that dominates the contemporary liberal western outlook — is that the universal drives out the particular, and the abstract triumphs over the concrete. Violence replaces patience.

Within the Church, it is the same temptation of legalism and rigidity that Francis constantly highlights: Jansenist rigidity, like ideology, is essentially anti-incarnational, by closing people off from openness to grace by detaching doctrine from human reality.

Once the universal (truth, law, doctrine) drives out the particular (concrete human realities, complex pastoral situations) it violates mercy, which is always attentive to the concrete and the particular. Truth and mercy form a unity in tension.

At the core of this kind of “in-the-tension” thinking — Francis uses the untranslateable Spanish word tensionante —the value of each pole is recognized and held together, rather than being resolved in contradiction. The synthesis that results is always an encounter between grace and nature, and is essentially the work of the Holy Spirit.

“The Christian is called to be a place of unity in the divisions of history, to bring the tragedy of the age into the presence of God who is always greater,” is how Borghesi summarizes Francis’s view of this dynamic understanding of the Christian’s role in the world.

Francis has applied Guardini’s thinking especially to the realm of politics. Unity comes about by allowing Grace to operate in the world, not by the avoidance of conflict nor by the imposition of an order, but as result of holding together opposing poles that allows for a synthesis that transcends yet at the same time preserves them.

Francis’s famous four institution-building principles in Evangelii Gaudium 222-237, which Borghesi here matches to the polarities deduced by Francis from Guardini, are ways of managing those tensions.

A key principle is that reality is superior to the idea. Unlike Hegelian dialectics which never turn back from their flight into abstraction, Borghesi shows that Bergoglio’s dialectics are essentially circular, in that the synthesis must always turn back to concrete reality, so that the new synthesis never degenerates into idealism.

In the same way, church doctrine – which is itself the result of a synthesis of law and pastoral practice – must constantly be re-rooted in pastoral realities, lest it descend into a kind of ethicism.

To understand Francis’s dialectical thinking is really to grasp the key to almost everything that is happening in this pontificate: the importance of mercy, the integration of pastoral practice into theology, his concern for concreteness and closeness, his horror of the technocratic paradigm, and so on.

In unpacking his thought, Borghesi has not just shown Francis to be a brilliant, and original thinker, closely connected in particular to Benedict XVI, but has given a masterclass in the effect of Grace on thought.

It is a book that badly needs an English-language publisher.

(Massimo Borghesi’s Jorge Mario Bergoglio: Una Biografia Intellettuale. Dialectica e Mistica is published in Italy by Jaca Book.)