ROME – Catholic history is a like a river fed by many currents, but one of the strongest and most perennial, undeniably and inextricably, is food. At the very heart of the sacramental system is a shared meal, and when we pray as Christ himself taught us, we ask for our daily bread.

Over the centuries, it’s incalculable how many turning points in ecclesiastical history have come over meals, from deals struck during the sumptuous pontifical banquets of the renaissance to whispered conversations in Roman trattoria during the Second Vatican Council.

Historically speaking, Catholic cultures always have generated some of the most lavish and developed culinary traditions in the world – think the foods of Spain, for instance, or Italy, or Brazil and Mexico.

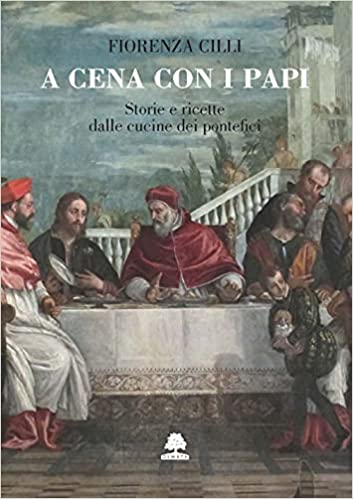

Thus it is that one of the most entertaining subgenres of Vatican literature has to do with popes and the food they ate. The latest entry on that list is the new titles A cena con i papi: Storie e ricetter dalle cucine dei pontefici (“At Dinner with the Popes: Stories and Recipes from the Kitchens of the Pontiffs”) by Fiorenza Cilli, an academic with a background in archeology who specializes in Roman history.

(My personal favorite of Cilli’s books is Rome Destroyed: The Demolitions of the City from nero to Today, which demonstrates why Rome is called the “eternal city”: Try as hard as you want to tear it down, it just keeps coming back.)

There are already plenty of “cooking with the popes” books out there, each interesting in its own way. For instance, I’ve always loved the contrast between the image of Pope Pius IX, the last “pope-king,” desperately struggling to cling to the monarchical pomp and privilege of the papal court, and his own terribly modest dining habits. Apparently, Pius IX had a rule that no more than one papal scudo could be spent on his lunches, which, in terms of purchasing power today, is maybe about $5. One of his favorite dishes was a version of Roman tripe with scrambled eggs as a substitute for the meat, eaten by the truly poor who couldn’t afford even cast-off tripe.

What makes Cilli’s new book distinct is that she isn’t so much interested in the literal menus particular pontiffs preferred, but rather dishes that evoke the particular era in which a pope served or in which major inflection points in church history unfolded.

For instance, Cilli offers two recipes to evoke the memory of the 1929 Lateran Pacts, the historic treaty between Pope Pius XI and Mussolini that resolved the lingering “Roman Question.” In essence, the papacy recognized the new Republic of Italy and agreed to stop demanding its territories back, and, in exchange, Italy ceded sovereignty over the 108-acre physical territory of the Vatican and also paid the Vatican a lump-sum compensation for its losses.

The broad Via della Conciliazione, which todays leads one to St. Peter’s Square, was built by Mussolini to celebrate the accord. (Trivia point: Families whose homes were bulldozed to make way for the avenue were resettled in the new Roman neighborhood of Garbatella about four and a half miles away, originally built by Mussolini to house port workers, and which is today regarded as one of the city’s most picturesque neighborhoods.)

The two dishes Cilli recommends are both things that were popular at the time, and which carry obvious symbolic resonance for an historic pact between the Vatican and Italy.

- Piazza bianca e gialla: A type of pizza composed of the colors of the Vatican flag, white and yellow, which uses both polenta and flour in the dough and comes with pine nuts and almonds on top along with ricotta cheese.

- Timballetto tricolore: “Tricolore” is what Italians call their flag, composed of the three colors of red, white and green, a “timballetto” refers to a crepe that’s sort in the shape of a kettledrum. In this case, the crepes employ red peppers, green spinach and white ricotta cheese, both in the flour mix and also, as cream sauces, poured over the top.

Nor is Cilli’s twinning of church history and good eating confined to the modern era. She reaches all the way back to the very first pontiff, St. Peter, and proposes a dish composed of sea bass with polenta and a sauce composed of anchovies, with chicory as a side dish – all things that were popular in mid-first century Rome, at the time tradition holds St. Peter arrived, though slightly adjusted for modern tastes.

For Pope Francis, Cilli suggests bagna càuda, a dipping sauce for autumn vegetables made principally of garlic, anchovies and olive oil – not necessarily because Francis is fond of it, but because it’s a typical dish of the Piedmont, the mountainous region in northern Italy where the Bergoglio family has its roots.

(I remember distinctly the day after the conclave in 2013 that elected Francis, headlines around the world trumpeted the election of a third world pope. Up north, however, it was, “Un Papa Piemontese!”)

The overall effect of contemplating these recipes, and, more so, trying them, isn’t so much to learn about popes as it is to enter specific historic moments, or specific places, and gain some of the living context that always helps flesh out one’s understanding of the figures who lived in those moments or places.

You have to go into with an open mind, because some of this stuff may not be quite everyone’s taste. If you don’t love anchovies, for example, bagna càuda won’t exactly light up your gastronomic scoreboard. But you will feel more connected to the broad Catholic story, and, as personal improvement projects go, eating your way through a history lesson isn’t the worst pedagogic strategy I can imagine.

Follow John Allen on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr