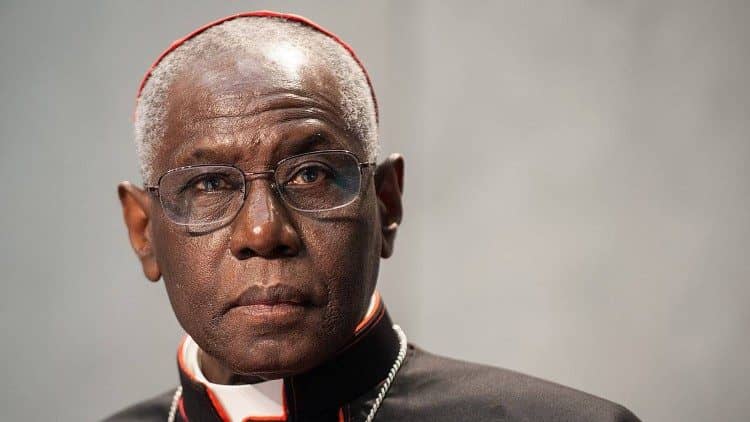

YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – Rwanda’s Catholic Church has not stopped grieving for the victims of the country’s 1994 genocide, according to Archbishop Antoine Kambanda of Kigali.

In a wide-ranging interview with The New Times, the prelate bemoans the suffering of millions of Rwandans and the more than 800,000 Tutsis massacred in the genocide – a genocide in which many Catholic priests played a role.

“The Catholic Church has never stopped weeping for what happened in Rwanda,” the archbishop said.

“The first voice of authority to say openly that what was happening in Rwanda was genocide was the Pope John Paul II, yet it took time for the UN to discuss and agree upon using the term genocide for what was happening in Rwanda,” he continued.

The archbishop commented on the fact that several members of the clergy were implicated in the slaughter, even directing the killing of people seeking refuge in their churches.

A report ordered by the Organization of African Unity on the genocide concluded that members of the Church had offered significant support to the Hutu regime during the killing, and that Church leaders had played a “conspicuously scandalous role” in the genocide by failing to speak out against it.

“And the position of the Church is that priests, the clergy, who were involved in the genocide, are to be tried for what they did and be held accountable. The Church does not say that because they were priests there is an exception, no, a crime is a crime. But the fact that a clergyman did that crime, it is not within the mission he was given, he abused and betrayed his mission, so it is not the Church which did it,” Kambanda said.

“However, as the son of the Church, we regret and ask pardon for that; the pope did it and the bishops did it in the Synod, there was a long process of asking pardon to God and to the community that the Genocide caused so much (harm). The guilt and wrongs the children do, the parents take upon, several times the Church has asked pardon to God and to the community,” he said.

On November 29, 2016, the country’s bishops issued a statement of apology about the role Church members played in the genocide.

Kambanda told The New Times that the bishops and Church are “still on the journey of unity and reconciliation in our communities, which suffered so much with a long history of divisionism that climaxed in the 1994 genocide perpetrated against the Tutsi which left many negative consequences.”

“The main duty that preoccupies us is that reconciliation and unity. And it is providential,” the archbishop said.

“Many have said the Catholic Church has not done enough to help Rwandans reconcile; some have pointed to a lack of institutional framework towards this end and only attribute the effort to the personal initiative of a few clerics,” he said.

“It is an essential part of our pastoral work such that is institutionalized, I don’t agree with people who may think that it is not institutionalized, right after the genocide, in the years 1999-2000, we had a synod which actually initiated and created ground and the way forward for reconciliation,” the archbishop continued.

“By then it was very hard, it was a very delicate situation with bitterness and fear and trauma and guilt. The approach we used was to share; such that each one narrates his or her suffering, and by sharing the suffering you listen to one another without judging. When people come to share their suffering that means taking upon yourself his/her pain and then you suffer for him or her and then you suffer with him,” he said.

Catholics make up around half the 12 million people of Rwanda, where religious groups have proliferated since the genocide, and the government last year said the number of recognized religious denominations had grown from 50 to more than 1,000 in the last 25 years.

In his interview, Kambanda also spoke about the Church’s opposition to the government’s contraception policy. In 2017, the government pledged to raise demand for family planning to 82 percent of the population.

“When we say we don’t accept the use of contraceptive methods, it does not mean we don’t accept family planning,” Kambanda said.

“We privilege natural family planning which is a package of building a family, natural family planning is built on dialogue and one of the things that destroys family is lack of dialogue, lack of communication to agree on what is to be done. Natural family planning is built on that and that package enables couples to do family planning in a natural way with respect for one another,” he explained.

“The contraceptives may dilute those values and there is a tendency little by little which builds a sense of using the other as somebody for pleasure and that paves way for violence. It may pave way for immorality among the youth, you know that self-control requires training, it is a whole philosophy and teaching which is a very important pillar for ensuring harmonious relations in the family, it is not about the pill or injection,” the archbishop explained.

Kambanda also said the future of the family in Rwanda was a major concern for the Church.

“Good families build a secure and stable country and society and prepare durable peace, so working upon the family we also assure reconciliation and unity in a community. If this spirit of unity and reconciliation begins from the family at home, it gives us assurance that it will last,” he said.