YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – In a strongly-worded letter addressed to the Bishop of Kumbo in Cameroon’s North West region, the Nso Cultural and Development Association, NSODA, have warned the Catholic Church against adulterating their culture “in the guise of inculturation.”

Social media has in recent days been inundated with videos of some of the most dreaded and sacred masquerades of the Nso people displaying in churches and church premises in Kumbo Diocese, all in the name of inculturation.

The displays have angered the people of Nso – one of the largest clans in Cameroon’s North West region.

NSODA – an association dedicated to the socio-cultural development of the Nso people – has expressed dismay at what they consider is an erosion of their culture.

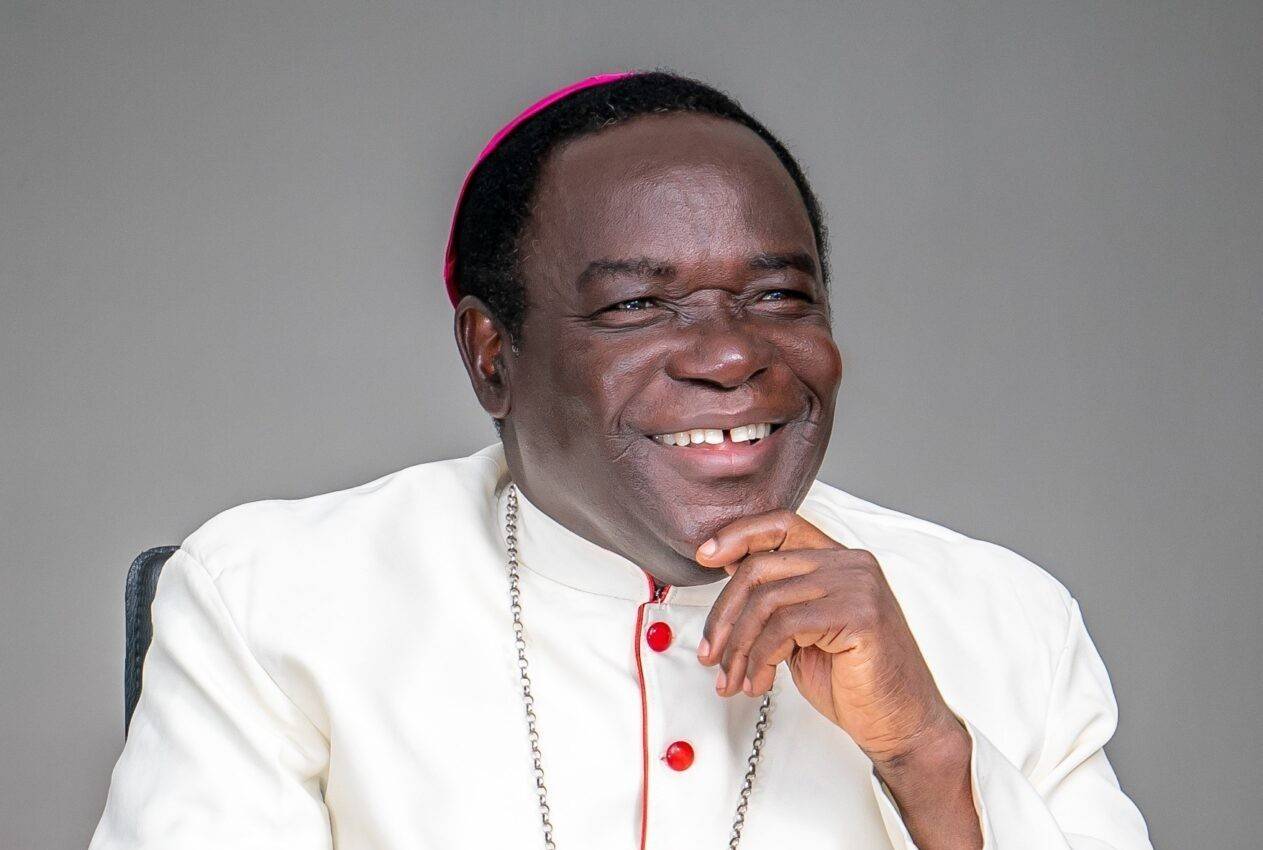

“We have not been oblivious to the efforts your Diocese has been making to the development of the Nso Kingdom, and the evangelization works that have been shaping our society,” writes NSODA President, Tadze Adamu Mbiydzela, in a June 4 letter addressed to the Bishop George Nkuo of the Kumbo Diocese.

“We remain indebted and sincerely grateful to your Lordship,” the letter states, before expressing anger at the displays of their sacred masquerades in Church premises.

Mbiydzela complained that the very idea of inculturation has been “wantonly and severely abused” by Catholics.

“The avalanche of those abuses inundated social media with shocking desecration of our culture and tradition,” he writes.

“A few instances which have caught our attention are moot shows in the Church or Catholic premises of our highly cherished sacred masquerades,” the letter states.

“We are totally dismayed that if care is not taken to protect our cultural heritage, which is our identity, then, with the passage of time, our culture will be completely eroded in the guise of inculturation,” he complains.

He explained that the Nso body polity “is built from her cultural heritage which, if not seriously protected, shall be lost, and Nso as a kingdom be eroded into an irretrievable abyss.”

“It therefore behooves us to strongly denounce to your Lordship these provocative moot displays of our culture on Catholic premises and elsewhere under the guise of inculturation,” the statement continues.

NSODA thus urged the bishop to “caution and counsel Catholic Christians or whoever is under your diocese to consequently refrain from those moot displays of our cultures in the name of inculturation.”

They threatened court action should those moot displays continue.

The Bishop of Kumbo did not reply to Crux’s request for comment, but Father Humphrey Tatah Mbuy, the spokesperson for the Cameroon Bishops’ Conference told Crux that Cameroon “has not even started inculturation.”

“We are at the stage of accommodation and adaptation,” he said.

He said adaptation means adapting to what exists, and noted that bringing masquerades to Church should have been predicated on a number of critical questions: What do those masquerades mean in the Nso culture and how would they help Christians become better Christians.

He said inculturation doesn’t mean bringing anything to Church, or singing any songs. Yet, some of the songs which unfortunately are being sung in Church have nothing to do with praising God. He said successful inculturation will require the expertise of anthropologists to ensure that whatever cultural approaches are used align to the fundamental principles of the Gospel.

Nathan Chase, an assistant professor of theology at the Aquinas Institute of Theology in St. Louis, Missouri, explains that inculturation, and liturgical inculturation, was a key part of the early Church but one that always provoked disagreements.

“Paul, for instance, argued about whether the Gentiles could be Christians. Justin Martyr argued that Greek philosophy could be used to describe the Christian faith. In every case, those in favor of inculturation, rather than those against it, won the argument,” he told Crux in an earlier interview.

“The Gentiles became Christians; Greek philosophy not only was used to describe the Christian faith, but would become central to the formation of the creeds in the fourth century. The early Church always accommodated itself to the cultures in which it was celebrated. Particular liturgies were developed in North African, where there was a strong Berber presence, Egypt, Nubia, and Ethiopia. Many of these were Hellenized African cultures, but still ones that were native to Africa. I would say the early Church actually was very responsive to other cultures. This broke down in the medieval period,” Chase said.

He said religion and culture are inherently connected, noting that Jesus was a Jew, while many of the early Christians were Greek.

“The fingerprints of Jewish and Greek culture are all over the Church. The issue is not whether they are connected, but how they should relate to one another. They must always be mutually informing one another, learning from one another, and at times critiquing one another. This is what is key: that they be in critical dialogue with one another,” he said.