YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – As Cameroon continues to grapple with a separatist crisis in its English-speaking regions—one that threatens the very foundations of the nation—a leading Catholic leader in the central African country has observed that tensions in the two regions are gradually easing. However, this does not mean the crisis is over.

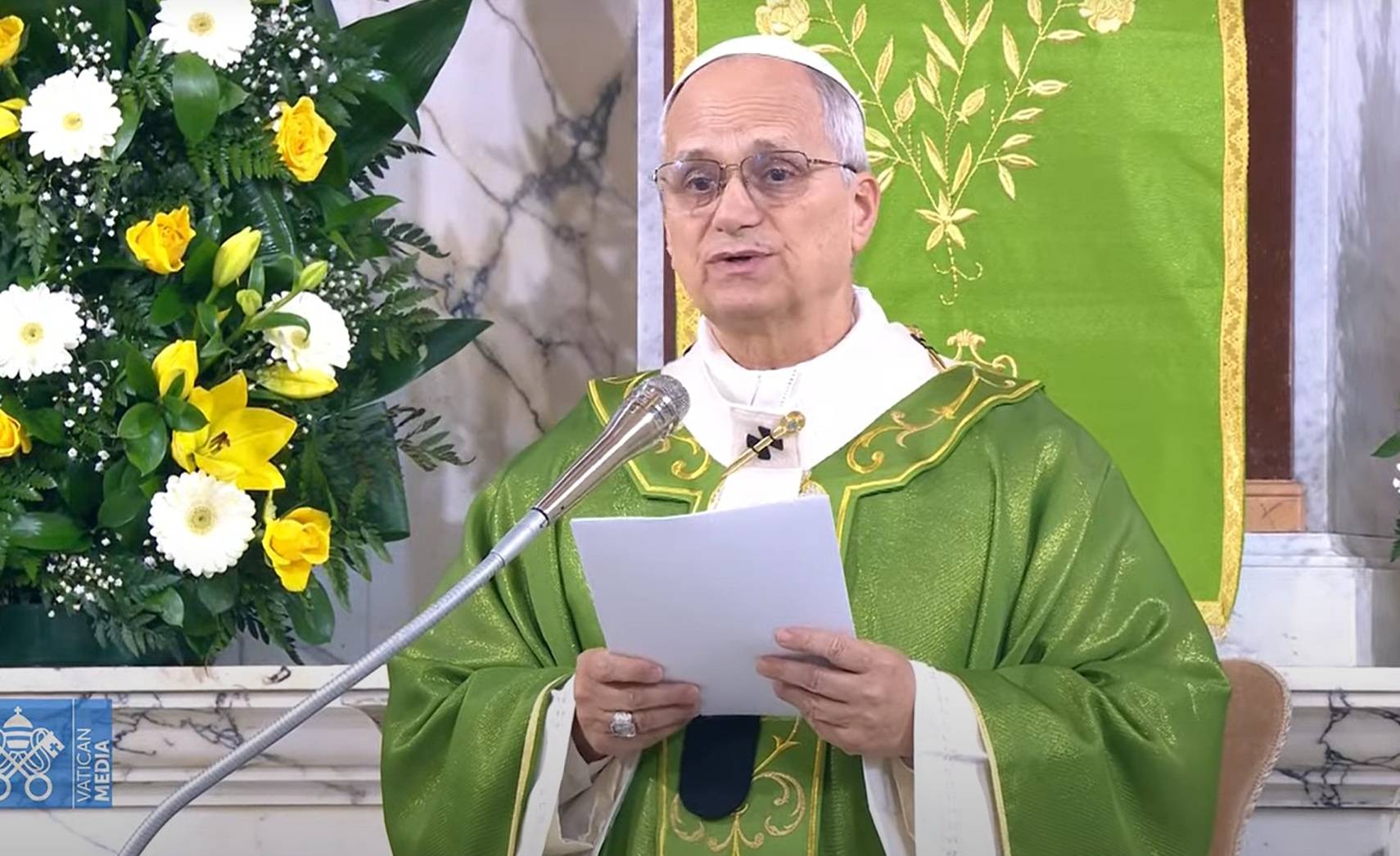

Archbishop Andrew Nkea Fuanya told journalists in Yaoundé on the sidelines of the 50th Ordinary Plenary of the Cameroon Bishops’ Conference that “things are getting better socially, but the crisis is very far from being over.”

The two Anglophone regions – the North West and South West – descended into violence in 2016 when a teachers and lawyers strike over the imposition of French in Anglo-Saxon schools and courts was violently suppressed by security forces.

That was only the trigger of a problem rooted in Cameroon’s colonial history. Initially colonized by Germany, Cameroon was divided between Britain and France when the Germans were defeated in World War I.

The two powers administered the two territories as separate entities until independence in the early 1960s when the two parts of Cameroon decided to come together as a federation of two co-equal states.

This federation lasted only a decade – in 1972 it was dissolved in favor of a unitary state. Anglophone Cameroonians viewed the move with suspicion, saying it was a ploy to assimilate them.

For decades, the feeling of assimilation and perceived marginalization among Anglophones crystalized and burst into the open in 2016.

For nine years, the conflict has cost the lives of over 6,500 people, with a million others forced from their homes.

Nkea has seen the crisis unfold – bearing witness to the daily pain and sorrow subjected to the people.

“I have been on the ground since the beginning of this crisis,” Nkea said. The first attacks took place in Mamfe in Cameroon’s South West region when Nkea was serving as the bishop of Mamfe.

“I witnessed a lot of suffering of our people, men and women escaping, some carrying their children, some lost their children in the escape,” he said.

He said many of the people escaped across the border to Nigeria where they were “sleeping under bridges, in abandoned houses with nothing to eat.”

“I went to Kembong village where many houses had been burnt down and there was a young man lying there who had been shot and dogs were feeding from his corpse and the only thing I could do at the time was take a stone and throw at those dogs to disappear for the time that we were there,” the archbishop said.

Nearly nine years down the line, Nkea says the social atmosphere is easing, but that shouldn’t be mistaken for the end of the crisis.

He said the separatists have relaxed their initial stringent calls for a school boycott “and therefore many children have gone back to school. “

“Businesses are reopening, and a sense of social life is gradually returning. Previously, in Bamenda, by 5:30 or at the latest 6:00 PM, everyone would rush home to lock their doors. But now, if you visit T-Junction or other parts of the city, you’ll find people out even at 8, 9, or 10 PM — gathering, drinking, and enjoying roasted fish,” Nkea said.

But the easing of the social climate doesn’t mean the crisis has come to an end.

“The fact that people are coming back, the fact that schools are going on, the fact that shops are opening more and more, the fact that people are beginning to celebrate funerals, more marriages openly and go right into the night, does not explain the end of the crisis. It is simply telling us that either people are getting used to the crisis or there is an uneasy détente,” he said.

It’s a perspective shared by Bishop Agapitus Nfon, the current bishop of Mamfe.

“Even if they call it calm, even if they speak of ‘normalcy’—that normalcy is merely superficial. And even if it exists now, it won’t last, because people are still suffering,” Nfon told Crux.

He said the use of military force as the only strategy toward ending the crisis is ill-advised, saying that it only silences people “through intimidation, not addressing the root cause.”

“And those in power must understand that some of our children, in primary and secondary school, have been radicalized. When they grow up without access to further education, without opportunities to build a future like everyone else, without employment or vocational skills to sustain themselves — they will return to the struggle,” Nfon added.

“If nothing is done, if real solutions are not put in place, they may continue to speak of normalcy. But it will be a normalcy steeped in pain,” he told Crux.