FORT WAYNE, Indiana — By most historical accounts, the 20th century was the bloodiest, most tyrannical period of modern times.

Two world wars, multiple other conflicts and the rise of brutal, totalitarian regimes prematurely ended the lives of millions and demanded the attention and action of nearly every country in the world.

Those who stood in defense of human dignity, justice and charity against the violence and totalitarianism of the time often paid with their lives. Hungarian Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty, by the grace of God, did not.

Around 1950, in Zanesville, Ohio, a young Patrick Flood’s Catholic grade school class watched a movie about persecuted Christians in the newly Communist countries of Eastern Europe. One, he remembers, was Mindszenty, then the bishop of Esztergom, Hungary, and today a candidate for sainthood. He was declared “venerable,” by Pope Francis in 2019.

Seventeen years later, the paths of Mindszenty’s mission and Flood’s career would cross.

Flood describes his younger self as being “very taken with my country.” A student of history, and later, political science and philosophy, he yearned for the opportunity to “show my dedication to the United States and the values that it stands for.”

Like his peers, he participated in ROTC in college. “We were ready to go,” he recalled in an interview with Today’s Catholic, newspaper of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend. The problem was, there was nowhere to send them. World War II and the Korean War were over. “But we did have a Cold War.”

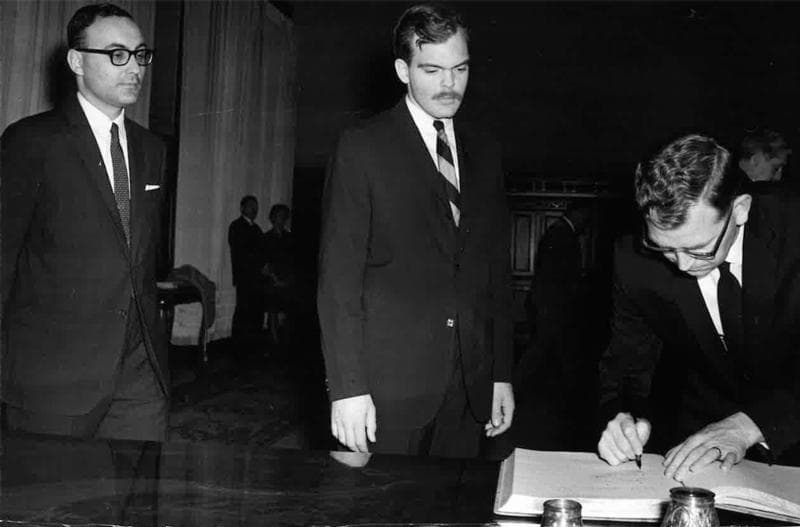

During college, Flood heard about the U.S. State Department Foreign Service, which offered the kind of challenge he was seeking. After passing the entrance exams, he was sworn in and assigned first to an office within the department and two years later to the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City as a consular officer.

In 1967, Flood was appointed chief of the Consular Section at the U.S. Embassy in Budapest, Hungary. It was there that he became closely acquainted with the preeminent symbol of Hungarian freedom and justice.

Appointed bishop of Veszprem by Pope Pius XII in 1944, Mindszenty’s protests against Nazi genocide led quickly to his arrest and imprisonment. He remained in prison until the Nazis were defeated in Hungary in 1945.

Following World War II, he was appointed to head the Archdiocese of Esztergom, Hungary’s primatial see. A short time later, he was named a cardinal.

In late 1948, Mindszenty was arrested illegally by the Soviet authorities who controlled Hungary. After a show trial, they sentenced him to life imprisonment under false charges. Even though his sentence brought protests from the pope, leaders of Western powers and the U.N. General Assembly, he remained in prison for eight years.

In late 1956, young Hungarian “Freedom Fighters” initiated a revolution against Soviet tyranny. Forcing their way into his prison, they freed the cardinal.

United to their cause and once again exercising his duty to promote social justice, in a Nov. 3, 1956, radio speech Mindszenty emphasized the value of national independence and democracy. On Nov. 4, 1956, Soviet forces that had invaded the city to quell the uprising sought his re-arrest. He took refuge in the U.S. Embassy, seeing an opportunity to serve as a symbol of continuing resistance to the domination being imposed once again on his nation.

When Flood and his family arrived in Hungary, Mindszenty had been in refuge at the embassy for 11 years. During all of that time the Hungarian secret police watched the embassy 24 hours a day, parking an unmarked car at each exit and staffing it with plainclothes officers who were eager to arrest the cardinal should he decide to leave the embassy — which he was free to do at any time.

In 1968, Flood’s responsibilities at the embassy were broadened to include acting as liaison to the cardinal. This entailed attending to any of his needs: for instance, providing books and facilitating occasional correspondence with the Vatican and visits from the cardinal’s family and representatives of the Vatican, notably the archbishop of Vienna.

Flood and other embassy personnel had a standing invitation to attend Mass celebrated by the cardinal on Sundays and holy days in his quarters. But among the moments most treasured by the lifelong Catholic from Ohio were the 7 p.m. strolls they took around the embassy courtyard.

“We would talk about many things, but mainly, my presence was about his safety and for companionship,” recalled Flood, now retired and a resident of Fort Wayne. This activity rotated among the American staff.

On one very cold January evening, the cardinal took his daily constitutional wearing a heavy cloak, but no gloves.

“I took mine off, to give to him, but he said, ‘No ‘– that he was used to the cold,” Flood remembered.

During his lengthy imprisonment, the cardinal explained, he had once asked his jailers if they would bring him a pair of gloves to enable him to say Mass in his cell. When they refused, he said, “‘Then I shall not need them.’ He added, ‘I have never worn gloves again.’ Such willpower is rare indeed.”

Among the cardinal’s few external contacts was a priest of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Msgr. John Sabo. A second-generation Hungarian-American priest and pastor of Our Lady of Hungary Parish in South Bend for 50 years, Msgr. Sabo had known of the cardinal and his work in Hungary for years and met him in person during the International Eucharistic Congress of 1938.

For many years Msgr. Sabo sent Mass intentions and stipends offered by Our Lady of Hungary parishioners to Budapest to support the work of the oppressed church in Hungary.

After negotiations with St. Paul VI, Hungarian authorities allowed the cardinal to leave Hungary in 1971. He died in exile in Austria in 1975. Once democracy was restored, his body was reburied in Hungary in 1991.

Flood said having the opportunity to get to know the cardinal was deeply inspiring, and that his service as liaison officer was an was an honor and a privilege.

“(His) unremitting resistance to the totalitarian ideologies of Nazism and Communism inspired the people of Hungary during the darkest decades of modern times. He was an authentic light in this darkness, a light that refused to be extinguished,” Flood wrote in an address to attendees of a 2019 conference in Budapest honoring the cardinal.

“He was one of my heroes. And I think he should be one of everybody’s heroes, because of the fact of his incredibly inspiring courage.”

Marlin is editor of Today’s Catholic, newspaper of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend.