When Germany surrendered to Allied Forces May 7, 1945, Catholics saw a nation and their church shattered.

Adolf Hitler’s destructive reign had turned many Germans into brutes or victims of the Nazis’ crazed megalomania. The Catholic Church suffered tremendously, even if some of its members were complicit in the Nazi regime. Millions of Catholics died on the battlefield, on execution blocks, in forced labor or in concentration camps. Some have since been beatified, a step on the path to sainthood.

One of the first was Erich Klausener, a 49-year-old civil servant who, on June 24, 1934, delivered a scathing anti-Nazi speech at a Catholic conference. Six days later, he was shot dead in his office by SS agents, the elite guard of the Nazi Party, during the “Night of the Long Knives,” when Nazis massacred political opponents. The Nazis claimed Klausener had died by suicide.

Two other prominent Catholics were murdered a few days after Klausener: Adalbert Probst, who headed a Catholic sports association, and Catholic newspaper editor Fritz Gerlich, who was murdered in the Dachau concentration camp, where he had been detained and tortured since March 1933.

Priests were persecuted too, though initially not subject to murder as easily as laypeople. Among traps set to intimidate and silence priests was to call a priest to perform the last rites in an apartment. When the priest arrived, a prostitute would throw herself at him while a Gestapo agent took “incriminating” photographs.

Father Bernhard Lichtenberg of Berlin, a persistent critic of the regime, was arrested in 1941 for drafting a sermon in which he was going to tell the faithful to reject anti-Semitic propaganda. After spending two years in jail, he died on his way to Dachau.

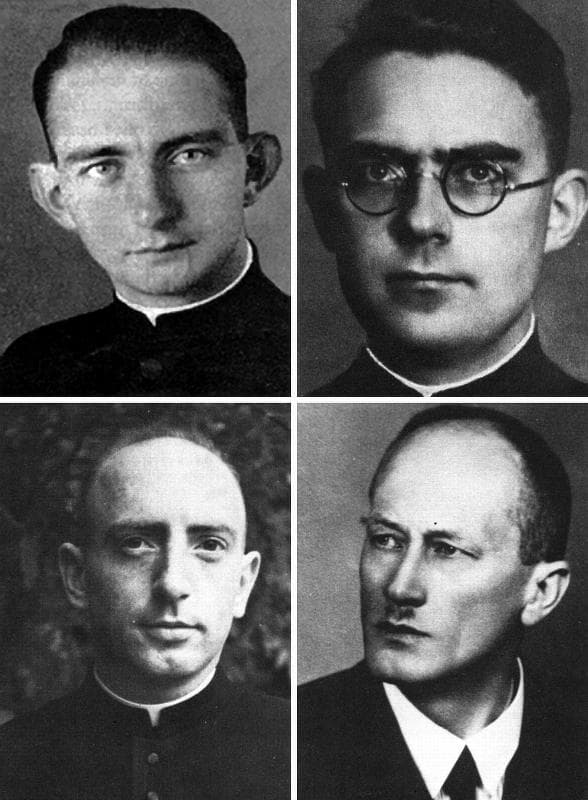

These murders and persecutions galvanized leaders like Bishop Clemens von Galen to speak out more forthrightly. His sermons influenced the White Rose resistance movement of students in Munich and, in the city of Lubeck, inspired Blesseds Johannes Prassek, Eduard Muller and Hermann Lange. The priests with their Lutheran counterpart, Rev. Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, were beheaded in 1943 after a show trial in a Nazi court.

Blessed Richard Henkes attracted the attention of the Gestapo for declaring the incompatibility between Christianity and Nazism. At Dachau, the priest was imprisoned with his old mentor, Pallottine Father Joseph Kentenich, founder of the Schonstatt movement.

Henkes became well known in the camp for his selfless acts of mercy. In the end, typhoid killed him before the Nazis could, on Feb. 22, 1945.

Another “Angel of Dachau” was Blessed Engelmar Unzeitig, a Marianhill priest who died a week after Henkes, also of typhoid. Like him, Unzeitig cared tenderly for prisoners with typhoid.

With its founder interred there, Dachau had a Schonstatt “wing.” Among the members was Blessed Gerhard Hirschfelder, who joined the Schonstatt movement in the camp. He had long spoken out against the Nazis, but what got him to Dachau was an objection to the destruction of Christian images. He died of starvation and pneumonia.

More than 1,000 priests from different countries died at Dachau, from disease or exhaustion or murder.

When Blessed Alois Andritzki asked for Communion, the guards mocked him. They killed him by lethal injection Feb. 3, 1943.

Blessed Otto Neururer was an Austrian whose crime was to counsel a young parishioner not to marry a man of dubious morals. It turned out that the man was a friend of the local Nazi chief, and the priest was transported to Dachau and then to Buchenwald.

There he was frequently tortured. After he illicitly baptized a fellow inmate, the camp commander hanged him upside down and naked. Neururer died May 30, 1940, after 34 hours.

Blessed Maria Restituta Kafka, a Franciscan Sister of Christian Charity, was the only woman religious to be formally sentenced to death by the Nazis.

An Austrian nurse in Vienna, she defied the Nazis by refusing to remove the crucifixes from hospital rooms and was also said to have dictated a poem mocking Hitler. She was beheaded at the age of 48 in 1943.

After serving as a chaplain in World War I, Father Max Josef Metzger, an ecumenist, became a peace activist. When World War II came, he was arrested several times by the Gestapo. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1944 after his memorandum to a Swedish bishop outlining how a defeated Germany could become part of a peace plan was intercepted.

Blessed Nikolaus Gross, trade unionist and journalist, was also a peace campaigner. When his Catholic workers’ newspaper was banned by the regime in 1938, he continued publishing it underground. He was arrested during the roundup following the failed assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944. Executed in January 1945, he left behind seven children.

One man who was killed for actually plotting to assassinate Hitler was Claus von Stauffenberg, an aristocratic army officer who had once been a keen Nazi. But the evils of Nazism offended Stauffenberg’s Catholic ethics, and he became a member of the resistance group called the Kreisau Circle. Stauffenberg was executed by firing squad.

The Kreisau Circle’s spiritual leader was Jesuit Father Alfred Delp, whose role was to explain Catholic social teaching to the group and establish contacts with Catholic leaders. As a parish priest in Munich, he helped to smuggle Jews to Switzerland.

He was falsely accused of being party to the plot to kill Hitler. In jail, the Gestapo offered him freedom if he left the Jesuits. Delp refused. He was sentenced to death and executed at the age of 36.

Some Catholics died because they refused to join the armed forces. Austrian Schonstatt Father Franz Reinisch said at his trial: “I am a Catholic priest with only the weapons of the Holy Spirit and the faith; but I know what I am fighting for.” He was beheaded.

These are just some of the German and Austrian Catholic martyrs to Nazism. Many more such martyrs came from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Italy and other places.

Simmermacher is editor of The Southern Cross in Cape Town, South Africa.