ROME – One of Christianity’s leading theological minds said Wednesday that believers who strive to make rational arguments for the faith in conversation with secularists should have fairly modest aspirations – basically, he said, their humble role is to keep a “foot in the door” until a saint comes along.

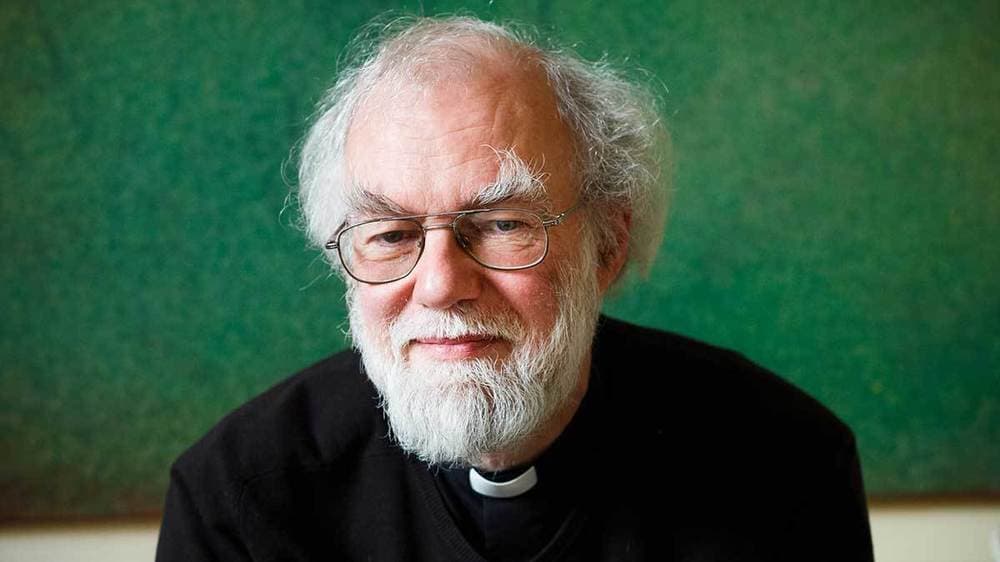

“You may not see this, but we do not inhabit completely separate universes,” is how Archbishop Rowan Williams, who served as the leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion from 2002 to 2012, put the message believers should strive to deliver to secularists.

“We continue to do so until there’s a moment of recognition,” he said, suggesting the most effective form in which such a moment occurs is an encounter with a role model of holiness.

Williams offered the example of Malcolm Muggeridge, a celebrated British journalist and satirist who was attracted to Communism in his youth and later converted to Christianity under the influence of St. Teresa of Calcutta.

“It was not argument, but seeing something fleshed out that did it,” Williams said, “but he wouldn’t have done it without steady engagement over the years with the arguments.”

“His world was not completely sealed off,” he said.

“There aren’t going to be scientists and philosophers queuing up at baptismal font,” Williams said, “but we can keep a foot in the door waiting for moment of grace to come.”

The 70-year-old former Archbishop of Canterbury compared apologetics with secularists to inter-faith dialogue.

“We are not after victory, but to establish the beginnings of common recognition, so that if ever the utterly clear voice of Christ speaks, it can be heard,” he said.

Williams spoke as part of the “JP2 Lectures” at the St. John Paul II Institute for Culture of the Dominican-sponsored Pontifical University of Thomas Aquinas, popularly known as the “Angelicum,” in Rome. The series honors the late St. John Paul II, who was once a student at the Angelicum.

The title of William’s lecture was “Faith on Modern Areopagus,” a reference to the scene in chapter 17 in Acts of the Apostles in which St. Paul introduced Christianity to the ancient Greeks, arguing that what they worshipped as an “unknown God” was actually the God of Christian belief.

Williams noted that in chapter 17, some of the Athenians scoffed when Paul started speaking about the resurrection, while others said “we should like to hear you on this some other time.”

“We should not expect the modern Areopagus to be any different, but I think it’s not insignificant that there were one or two who did respond,” he said. “God is interested in every single soul, so that’s not a waste.”

“I think that’s an encouragement,” he said. “He’s opened some small space in their minds and hearts.”

The heart of Williams’ argument was that despite the strong devotion to human rights characteristic of the modern Areopagus, there’s no firm basis for upholding universal and inherent human dignity without worship of a transcendent God.

Otherwise, he said, human rights inevitably become circumscribed on the basis of capacity, or ethnicity, or some other consideration. He offered the example of widespread selective abortion of fetuses diagnosed with Down syndrome, such as in Denmark, where only 18 Down children were born in the entire country in 2019, and in Iceland, where the syndrome effectively has been “eradicated.”

“The implication has not been on lost on those living with Down syndrome and their families,” Williams said. “It implies a prescribed norm of human capacity, and thus a failure [on the part of Down individuals] to earn the usual human standard” for recognition of their rights.

“It’s familiar argument from the 18th and19th centuries, as well as the early 20th century,” he said. “That’s not a happy ancestry.”

Williams invoked the late French philosopher and social critic René Girard to contend that without a transcendent deity to ground a sense of inherent human dignity beyond anyone’s power or control, humanity generally ends up with “an act of collective or violent exclusion, a sacrificial process.”

“Human beings see themselves as living precariously, in incessant rivalry with others,” he said. “We seek to circumvent that risk by making the desires of others their own. Those others become a profound threat, endlessly intensified competition, so cohesion is secured by identifying a collective candidate for exclusion, which leads to scapegoating, expulsion, even murder.”

Scapegoating, Williams said, is the “ultimate toxicity for the world.”

Only God, Williams said, offers the universe “unconditional, unacquisitive affirmation.”

“Ineradicable rights and universal human dignity, seen not simply as the corporate decision of human majority, stand in need for grounding, Christian and Christocentric anthropology supplies it,” he said.

Christianity, Williams said, allows humanity to “come to see the action of a transcendent source of affirmation upon ourselves and our world, to identify with an act that breaks the mimetic spiral,” so that Christian doctrine is “the way in which the hidden truth about humanity is allowed to come to light.”

Christianity, Williams argued, fosters a “non-competitive, non-revengeful, non-violent engagement with others.”

It’s based on “worship of that alone which is truly worthy of worship, which does not contend with or displace finite action, and which is able to work through a reality radically opened up to be more completely a vehicle for the eternal act of gift.”

In that light, Williams also invited would-be defenders of the faith to a certain humility about their own role.

“The survival of Christian faith does not depend on our resources or ingenuity,” he said. Invoking Jewish holocaust victim Etty Hillesum, he suggested the more modest aim ought to be to “live in such a way that it makes sense to say God lived in these times.”

Follow John Allen on Twitter at @JohnLAllenJr.