SYDNEY — After a prominent Australian university announced it had made artificial human embryos from skin cells, an Australian archbishop with a doctorate in bioethics asked, “Is this really such a good thing?”

Sydney Archbishop Anthony Fisher said people should “dial down expectations that these artificial embryos will cure disease or alleviate suffering,” noting that the same thing was said about embryonic stem cells and gene therapy.

In a column in the The Catholic Weekly, newspaper of the Sydney Archdiocese, Archbishop Fisher noted that with stem-cell technology, “the majority of the licenses granted went not to those institutions researching cures for disease or spinal cord injuries, as promised, but to the IVF (in vitro fertilization) industry that pulls in revenues of half a billion dollars each year in Australia alone.”

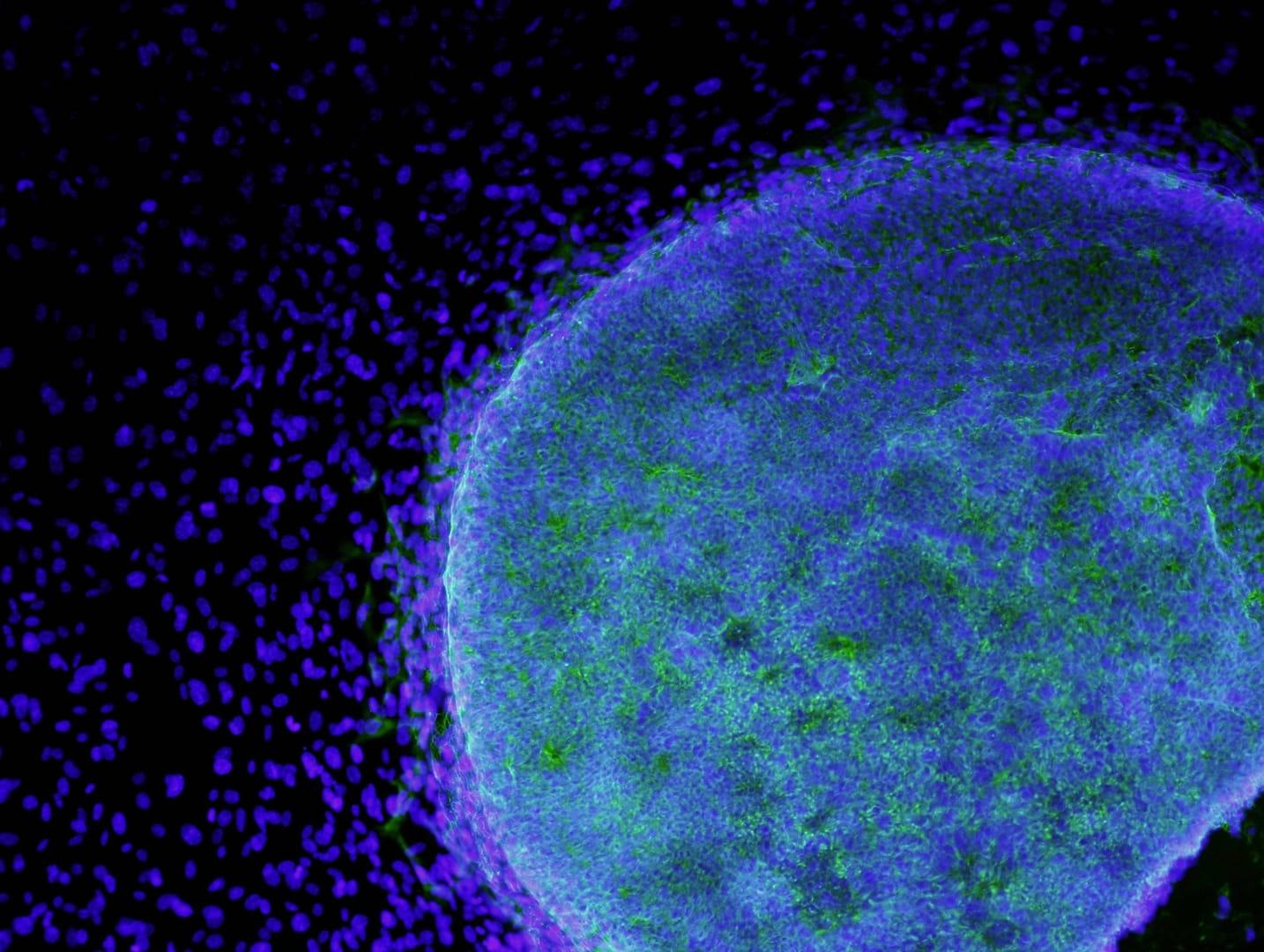

An international team of scientists led by Monash University in Melbourne announced in mid-March that it had succeeded in generating the artificial embryos by changing the cellular identity of human skin cells that, when placed in an extracellular matrix, organized into blastocyst-like structures, which were named iBlastoids.

But in his column, a shorter version of which ran March 20 in The Australian, Fisher noted the Embryo Research Licensing Committee was calling the iBlastoids embryos.

“As the saying goes: ‘If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, and swims like a duck, it’s probably a duck.’ So, too, with an embryo: If it has human genes, develops as a human being develops, and does the things a human embryo does, it’s probably an embryonic human being,” the archbishop wrote.

“Nature already provides for a significant variance in early human development. Those human embryos that do not develop exactly as expected because of some chromosomal abnormality or other genetic issue are still embryonic human beings, and it would be outrageous for anyone to suggest these were not human, just because their development did not appear ‘normal. Until we know for certain, we must give these embryonic humans the benefit of the doubt.”

He noted that if the organisms “do not have such a developmental trajectory, then they might not be bona fide embryos after all. In that case, there might be ethical uses for them, and we would support and encourage such ethical use.”

“We should be suspicious of those who rush to characterize them as no embryo at all, particularly when they stand to benefit from this type of dehumanization,” said the archbishop, who holds a Ph.D. in bioethics from the University of Oxford. “This could just be an Orwellian way of ensuring no one feels too queasy about the laboratory manufacture of human lives for experimental purposes or that no one engages in much scrutiny of the project.”

“We should all take a deep breath and ask: What’s the moral cost and where is this taking us as a community? Has the ready expendability of early human life now become an acceptable social norm?” he asked.